Motherwell split on identity ahead of independence vote

- Published

It is exactly six months until Scotland votes on whether to break away from the UK

I first went to Scotland as a teenager on a school trip on a sailing training course. Pembrokeshire to Glasgow by train was the longest rail journey I had ever undertaken. It took the best part of 18 hours - much of it overnight.

Thirty years on, I remember the sheer distance I had travelled from home on my own. Scotland was another country.

Thirty years on, I'm back in Scotland and the political landscape is being reshaped.

From Cardiff, it's a six-hour drive to Motherwell in North Lanarkshire. My home in Wales is only two hours from Westminster - London is a day trip away.

But Scotland is much further from the seat of UK government power. It's an obvious thing to say but Scotland's geographical distance from London also partly explains why Wales is so far from Scotland's independence vote. We're geographically closer to London and perhaps still politically closer to Westminster.

In six months, Scotland will vote on independence.

But I want to know why Scotland's nationalists are in government and powerful enough to offer the prospect of independence and yet in Wales, voters have largely ignored nationalism and independence doesn't appear to be on the radar.

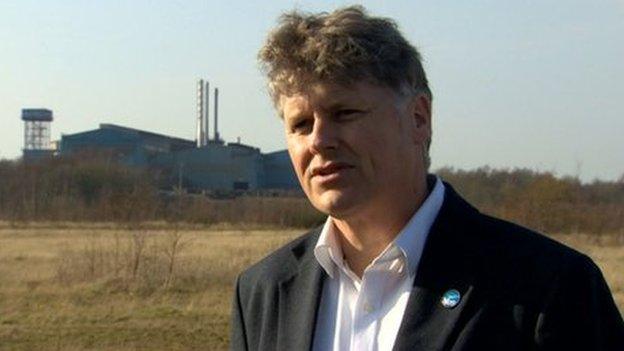

I've come to Motherwell to the site of Ravenscraig steelworks to meet Colin Fox, leader of the Scottish Socialist Party.

His grandfathers and uncles worked here before British Steel mothballed the plant.

Like Welsh towns including Ebbw Vale, Motherwell's wealth and purpose almost disappeared overnight.

Colin tells me: "Scotland watched as British Steel pulled out. Without British Steel in Motherwell, Motherwell stopped looking to Britain and defined its future - not as British - but as Scottish."

He says, if Scotland votes yes in the referendum - the campaigners will owe a debt of gratitude to Margaret Thatcher and her government's industrial policy in the 1980s.

He says, Ravenscraig's closure explains the Conservative Party's virtual annihilation in these parts but what is significant is that increasing numbers of disaffected working class voters placed their trust not in Labour but in the Scottish National Party (SNP).

Colin Fox says the closure of the steelworks in Motherwell set about a change in the way people felt about Scotland's relationship with Britain

These days, the SNP is in government in Scotland, and recipients of support from those who might have once backed Labour. Despite a generation of the Scotland-educated Tony Blair and Gordon Brown dominating Labour at Westminster, Scotland's political compass is set by the SNP.

So why is Scotland voting on independence - and yet Wales not even mentioning the word?

Early in the morning, Glasgow University is my first stop of the day to find answers to Scotland's journey to a referendum.

Prof Duncan Ross, has granted me his first tutorial. Why does he think independence is on the agenda in Scotland but unspoken of in Wales?

He says Scotland was never conquered and to this day views itself as a sovereign country with its own long-standing legal and education system.

Its institutions' age gives the country a confidence and swagger of a dominant neighbour that Wales can only dream about. Scotland's experience of Westminster's political parties is viewed as highly centralised, distant and reluctant to devolve power.

Devolution delivered

Prof Ross says people who support the yes campaign say Scotland has the wealth to see it through - but there is something else in the mix too.

Devolution has been a success here. The SNP's stewardship of Scotland's health, education and inward investment has been successful.

Even some of the government's critics will tell you Alex Salmond's government has delivered on devolution.

In contrast, in Wales, a recent BBC poll on St David's Day suggested nearly a quarter of people want to abolish the assembly.

But don't run away with the thought that everyone in Scotland is about to vote yes.

On the other side of Motherwell, in Dryburgh Road, members of the Orange Order, are gathering for the weekly old folks' lunch.

Jim McNab says he will leave Scotland if it wins independence

Jim McNab is in charge. He's an Orangeman. I ask him if he thinks of himself as British or Scottish?

Jim is the first person to tell me that he will leave Scotland if his fellow countrymen vote yes.

There's no real equivalent to the Orange Order in Wales, no similar organisation that declares its undying affection to the Union of the United Kingdom.

In Scotland, the Orange Order's members are the standard bearers of keeping Britain together.

These men and women want to keep the Queen, the monarchy, Westminster's power over Scotland and see off republicanism, separatism, the SNP and independence.

The country is plastered in yes campaign posters, but he says the no campaign is keeping its powder dry.

Most of the people at the lunch are elderly but representative of a large chunk of Scottish society - those who think devolution has delivered - but want to stop any further constitutional change at the next opportunity.

Meanwhile in Motherwell town centre, it looks much the same as every other town in Britain.

There's the inevitable pedestrianisation, the string of familiar chain stores, businesses fighting to stay alive in the face of internet shopping and out of town retail.

But everywhere you walk there are reminders of the coal and steel industry that once dominated the landscape.

The pit-head winding gear sits at the side of a roundabout - the scene so familiar in regeneration towns like Ebbw Vale.

For all its similarities to Wales, our shared industrial past, memories of the coal and steel, there is something economically different about Scotland.

And that is oil - and whatever the arguments over its future and its value - it is a significant factor fuelling the argument over Scotland's viability as an independent country.

The Scottish referendum will be the first time Jennifer Winter, 16, will be allowed to vote, but her dad Brian thinks she is too young

Jennifer Winter is 16 years old and joins a generation of young Scots who will be eligible to vote for the first time in this referendum.

She is taking part in BBC Scotland's Generation 2014 which follows 50 young people aged 16 or 17 who are eligible to vote in the referendum.

We sit round the kitchen table and flick through the encyclopaedia-like book that 16-year-olds have been given to help them decide how to vote. It looks un-thumbed.

Her father Brian says he's voting no. His mind is made up. No amount of campaigning or canvassing will sway him now. "Scotland can't afford to go it alone," he says.

His view is forget the dreams and the romanticism, this all comes down to money and Scotland can't afford it. And he certainly doesn't think that someone like his daughter, who has never worked and never paid tax, should have a say.

Jennifer hasn't decided how to vote. It'll be her decision and not her dad's she says. But she's been interested to watch the interventions of the businesses in Scotland who say they'll pull out if it's a yes.

Watch more on Jamie Owen's Postcard from Scotland on BBC Wales Today at 1830 GMT on Tuesday.

- Published9 September 2014

- Published28 February 2014

- Published16 March 2014

- Published17 March 2014

- Published7 March 2014

- Published12 March 2014

- Published13 February 2014