Measuring devolution: Big era of change for education

- Published

People in Wales have mixed views on whether devolution has worked for education

Has devolution made a difference? You would be hard-pressed to look at education policy and conclude that nothing has changed.

Take higher education. Welsh students pay about £3,500 in tuition fees with the Welsh government paying the rest, wherever they choose to study in the UK. It's distinctively different from the English and Scottish approaches, but it's costly too - a review is underway looking at whether the policy needs to change in the medium-term.

Schools have also introduced a foundation phase for three-to-seven-year olds, and reforms carried out over the border - academy schools under Labour, free schools under the coalition - have been rejected here.

But are standards slipping? The latest Pisa international comparisons showed Wales falling behind the rest of the UK in reading, maths and science, and even the education minister admits Labour "took its eye off the ball" in the early years of devolution. Education correspondent Arwyn Jones has been looking at whether different really does mean better.

Few areas have seen such obvious changes since devolution as education.

For parents and pupils, lecturers and students, the way our schools, colleges and universities work here is very different to the days before the creation of the assembly.

It's also very different to what happens in other parts of the UK.

Scrapping school league tables in 2001, external and Standard Assessment Tasks tests in 2004, external were tangible changes in the early years, when the then Education Minister Jane Davidson was still getting to grips with her new-found powers.

And yet, when he looked back to those days at the end of last year, the current Education Minister Huw Lewis said:

"I think there are questions that could be raised around taking our eye off the ball in the mid-2000s, around the basics in education, around literacy and numeracy. We've certainly put that right."

So what happened? What does Mr Lewis mean by "taking our eye off the ball"?

When Ms Davidson got rid of Sats, the plan was to replace them with a different set of tests, but that never happened.

Prof Richard Daugherty said there had not been enough long term thinking

The man who recommended the new tests a decade ago was Professor Richard Daugherty, who now works at Oxford University.

He thinks scrapping Sats without replacing them was a mistake because it meant we could no longer measure how children were getting on.

"It's also partly about asking how well are our schools doing? How well are our primary schools doing? How much of a problem is there with literacy at 11 or numeracy at 11?" he says.

"That's a valid question that everybody wants to know about and an important question. But you've got to have evidence to do that. And unless you put the systems in place to provide the evidence you can trust, you're not going to be able to use the evidence.

"That's the problem; it's not so much the problem of having a stick to beat the schools with - as some people would see it as. It's actually, at every level of the system having good enough evidence to enable you to pick up what is going well and what needs to be done to improve things."

We know Wales has slipped down the international education league tables, Pisa. But as important as they are, there are many concerns about how Pisa works.

Professor Chris Taylor of the Wales Institute of Social & Economic Research (Wiserd) at Cardiff University says there is a more accurate way of monitoring how our education system here compares with the rest of the UK.

The Millennium Cohort Study (MCS), external is following the lives of around 19,000 children born in the UK in 2000-01, including just under 3,000 in Wales.

Prof Taylor says: "They could be called the 'children of devolution'."

"Crucially, when we compare children in Wales with elsewhere in the UK, with very similar circumstances, from very similar backgrounds, similar households, they do slightly less well in their literacy test results, they do about the same in their numeracy tests.

"But they do better in other cognitive measures [like forming ideas and reasoning], which allows us to consider their other qualities."

So there we have it, worse at reading, about the same in maths, and better at how our children are taught to think.

But that does not really tally with what we see in the GCSE results. Or does it?

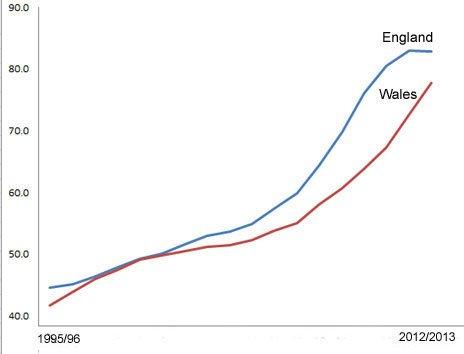

Percentage achieving five GCSEs A* to C or equivalent over time

The graph above shows the percentage of pupils in Wales and England who got good GCSE grades - A* - C grade from the mid-1990s.

In 1999, we are neck and neck. But if you go along, by 2011 you see the gap between the two countries growing as England motors ahead.

But that is not the whole picture, according to Prof Taylor, because the results used by the Welsh and UK governments do not just count GCSE results, but vocational courses too.

So maybe the fears about our results are not all that well founded after all.

"Importantly, in Wales, fewer children undertake equivalent qualifications: B-Tecs, NVQs.

"In England, schools are much more likely to push children into those routes instead of GCSEs and in many ways it's that difference which accounts for that apparent gap in GCSE or equivalent qualification performance."

Learning through play was brought in three years ago

Possibly the biggest change we have seen in education in Wales is the foundation phase, external.

Our youngest children are now taught through play, the idea being you instil a love of learning at an early age. But despite having been in our schools for four years, the way it is taught is inconsistent, according to recent government reports.

Prof Daugherty was asked by the Welsh government to look into how it were implementing policies in the early years of devolution.

He found it had a bit of a scattergun approach to new policies - and did not really keep track of how new initiatives were getting on. He thinks the civil service here just was not up to the job in 1999.

"The Scots had their own parliament in 1999 but the officials there had been making education policy for many years and they were used to sitting down with people and thinking through what should be done and how it should be done," he said.

"And so once they had a parliament all they were doing was relating that to the elected members of the Scottish parliament.

One study is following 3,000 children from Wales born in 2000-2001 and compares them to 16,000 in other parts of the UK

"In Wales they had none of that experience."

Those early years of devolution saw a whole raft of new education policies.

Schools, colleges and universities here now look very different to back then.

But in the world of education policies, changes happen slowly. So perhaps the full impact of devolved education in our schools is yet to be felt.

- Published27 November 2013

- Published21 May 2013