World War One: Cycle maps, pigeons helped intelligence

- Published

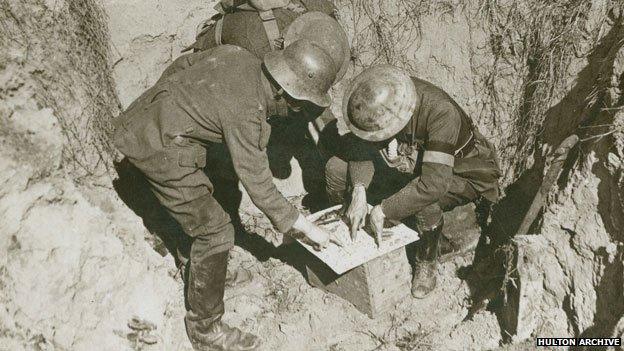

A German prisoner showing the location of his unit in 1918

When war broke out in 1914 around 30 to 40 "rag tag and bobtail academics, artists and musicians" received a telegram from the War Office.

They were ordered to go to Southampton as they were now intelligence officers in the newly formed Intelligence Corp.

"They were mainly chosen because they spoke French or German," said Tristan Langlois from the National Army Museum in Chelsea.

"Their training, he said, was almost non-existent. They were trained to ride a motorcycle or a horse.

"They were then sent to France with the instruction to make themselves useful and told to pretty much get on with it."

It is hard to imagine intelligence gathering had such humble beginnings, when it is now at the heart of every decision made by the modern British Army.

At the barracks of 1st The Queen's Dragoon Guards at Sennelager in Germany, Captain Rupert Robinson - whose family are from Swansea - outlines the requirements of the role now.

"I have to understand how the enemy is going to act and how he operates to assist the commanding officer in how he wants to conduct operations," he said.

To carry out that role effectively, Capt Robinson says it is about collating and analysing information from a number of sources.

He added: "I have reports which come in from all sorts of different intelligence gathering and agencies. I'm looking to see what the big patterns are and picture is."

With advancements in technology, that information is constantly updated.

To find out how the role has evolved from a handful of men chosen for their language skills I accompanied Capt Robinson to The Royal Signals Museum at Blandford Camp in Dorset.

Intelligence coo - a carrier pigeon having a message attached to it

Capt Rupert Robinson studies a WW1 map

'They used maps you might use to plan your summer holiday'

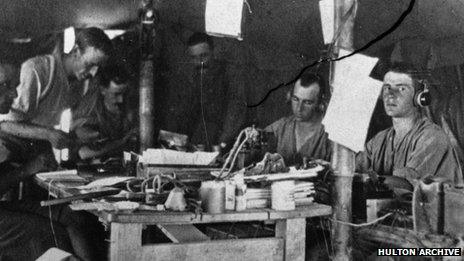

Inside the signal tents at divisional headquarters in Gallipoli

Air warfare also meant air intelligence

The archive contains tens of thousands of documents including aerial photographs and maps from World War One.

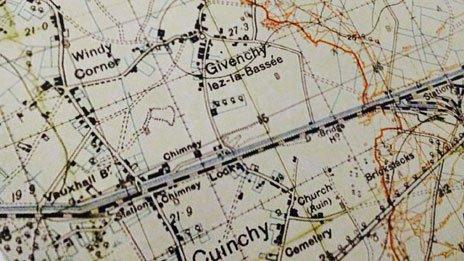

Adam Forty from the museum showed us some of the typical maps those early intelligence officers had access to.

"They were sent to France with automobile road maps for cyclists and cars. They didn't have sophisticated military maps yet," he said.

The maps are fairly basic, with markings of the major roads and settlements. For Capt Robinson that was a surprise.

"It's amazing to think they used maps you might use to plan your summer holiday," he said.

Reporter Charlotte Dubenskij went to meet Captain Rupert Robinson from 1st The Queen's Dragoon Guards

"The level of detail we expect in our mapping today and how quickly we can get hold of it, makes us very fortunate."

The information the budding Intelligence Corp had access to may have been crude by today's standards, but the unit soon became essential to the war effort.

"Once the trench lines had stabilised, the Intelligence Corp really got into gear," said Mr Langlois.

"The kinds of intelligence they began to gather are pretty much the kinds of intelligence which are still gathered by their counterparts now.

"This included examining and searching prisoners for documentary information. That was combined with new kinds of technological innovations such as aerial photography."

Mapping is far more detailed today says Capt Rupert Robinson

But while technology was rapidly developing during the conflict, there was still a reliance on more bizarre methods to find out what was happening in enemy territory.

"The British Army used spy pigeons," said Mr Langlois.

"They would drop baskets full of pigeons behind enemy lines by parachute.

"The homing pigeons would have labels attached to them explaining to locals that if they had any interesting information they were to attach it to the bird and release it."

Surprisingly this did produce results.

"An enormous amount of very valuable information was gathered this way," he added.

Such was the importance of pigeons more than 100,000 were used during the war to send messages. As well as spies of the feathered variety, dogs were also used to dispatch information on the battlefield.

For Capt Robinson there are some similarities with his current role in Afghanistan. He is helping to train up the Afghan National Security Force (ANSF) as part of the final handover before British troops withdraw from the country.

"The ANSF doesn't have access to a lot of the technology and systems that we do. So actually looking back 100 years at what was available then and what they (ANSF) have now, there's actually quite a lot of parallels that can be identified," he said.

- Published20 June 2014

- Published18 June 2014

- Published16 June 2014

- Published17 June 2014