World War One: Medical advances inspired by the conflict

- Published

St Fagans Castle near Cardiff was used as a hospital for soldiers injured in the war

In its scale and devastation, World War One was unlike any before.

New heavy artillery and machine guns obliterated flesh and bone. And even if a soldier wasn't instantly killed the dirt of the trenches meant wounds often became infected.

Millions died, and millions more were left disabled which, according to retired anaesthetist Dr Peter Lloyd Jones, secretary of the Museum for Health and Medicine for Wales at Cardiff University, led to huge new challenges for the medical profession.

"The weaponry was far more effective - 15% of all combatants in the British armed forces were killed and that was unprecedented," he said.

Owain Clarke reports on how World War One led to advances in medicine

"On the other hand, of those that got injured but didn't die, far fewer than before died of their injuries and that has to be down to well organised medical management."

Faced with such carnage, the medical profession did, indeed, respond.

And two Welshmen were responsible for one of the most important advances - the Thomas splint - which is still used in war zones today.

It was invented in the late 19th Century by pioneering surgeon Hugh Owen Thomas, often described as the father of British orthopaedics, born in Anglesey to a family of "bone setters".

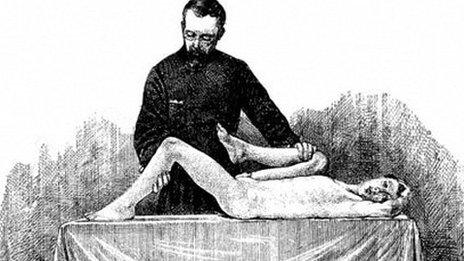

Sir Robert Jones operating in the early 1900s

But it was his surgeon nephew Robert Jones, later Sir Robert, who as a major general inspector for orthopaedics in the military, was mainly responsible for rolling out its use on the battlefield in World War One.

At the beginning of the conflict in 1914, 80% of soldiers with broken thigh bones died. The use of the Thomas splint meant that, by 1916, 80% of soldiers suffering that injury survived.

But there were other significant advances, including more widespread use of treatments and vaccinations for deadly diseases like typhoid.

In France, vehicles were commandeered to become mobile X-ray units. New antiseptics were developed to clean wounds, and soldiers became more disciplined about hygiene.

Also, because the sheer scale of the destruction meant armies had to become better organised in looking after the wounded, surgeons were drafted in closer to the frontline and hospital trains used to evacuate casualties.

Those lessons are just as relevant in war zones today.

Military medics at Camp Bastion, Afghanistan, in 2011 receive a battlefield casualty

Colonel Tina Donnelly, a nurse and army reservist who was commanding officer of the field hospital in Camp Bastion in Afghanistan, said their knowledge of how to treat leg injuries on the battlefield went back to their forefathers.

"Today we might not think of those injuries as being life threatening but in the First World War they would have been," she said.

"If you fracture your thigh bone, minimum blood loss is about one and a half litres from a circulating volume of about five litres - not to immobilise would have been life-threatening."

With hundreds of thousands of injured soldiers returning home, World War One also led to a new emphasis on rehabiliation and continuing care.

New techniques in facial surgery and burns were developed - and there were huge advances in prosthetic limb technology - to meet the needs of hundreds of thousands of amputees.

And with existing healthcare capacity overwhelmed new hospitals were built across the country, including the Prince of Wales Hospital in Cardiff.

Dr Lloyd Jones said this transformed the shape of the healthcare system.

"Generally speaking medicine in Britain was pretty disorganised," he said.

"You'd have a GP, you might have a cottage hospital down the road run by some local benevolent body, but there was no organisation - nothing bringing it all together.

"And that's what the First World War did for Britain."

- Published16 June 2014

- Published21 July 2013

- Published5 August 2012