Nathaniel Wells' rise from slavery to slave owner

- Published

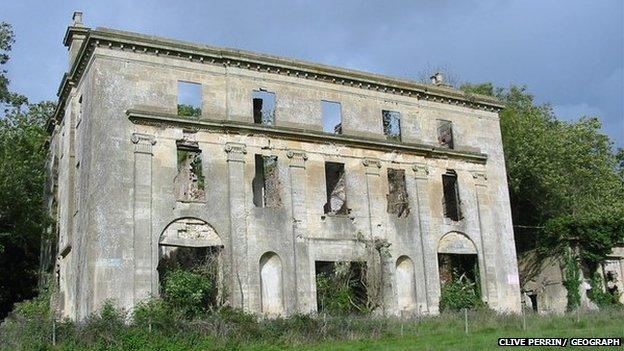

The ruins of Wells' Piercefield House sits near Chepstow racecourse

In many respects, Monmouth's Nathaniel Wells was a typical 19th Century gent, with his fortune built on the back of slavery.

The only difference between him and his contemporaries was the fact he was actually born a slave himself.

While his colour would have denied him the vote in his native Caribbean, he passed judgement on white people as a justice of the peace in Monmouthshire.

Records show that owners frequently fathered children with their slaves. But very few offspring went on to own the plantation on which they were born or achieve what he did.

Born on St Kitts in 1779, Nathaniel was the son of William Wells, a sugar planter and merchant, and his enslaved house worker, Juggy.

Instead of facing a life of slavery himself, he was sent away to school in London at 10. Nathaniel then went on to marry the daughter of George II's royal chaplain, and served as justice of the peace, high sheriff and church warden from his country estate near Chepstow.

In 1925, a group of ten businessmen bought Piercefield House and created Chepstow Racecourse on the site

While such a rise to prominence would have been rare, it is likely that a quirk of fate helped Nathaniel.

"William Wells' English wife had died shortly after he arrived on St Kitts, so although born a slave, Nathaniel was his only surviving heir," said doctor Nick Draper of University College London's Legacies of British slave ownership project.

"In truth his story is so unusual that it's difficult to read too much into what it says about the prevailing attitudes of the time."

'Firm but fair'

Dr Draper says Nathaniel Wells would have known very little of the slave life, as William Wells sent him to be educated in London from the age of 10.

Although contemporary sources comment on his colour, his manners, education and wealth meant he was able to fit into British society.

"In the late 18th and early 19th Century there was still an attitude that people from other societies could be taught to live up to British ideals. Ironically, had he been born fifty or a hundred years later after slavery, it's doubtful that he'd have been able to rise to such an extent, as attitudes to race hardened somewhat in the Victorian age," Dr Draper added.

Typical of the kindly yet curious reactions Nathaniel Wells faced was that of landscape painter Joseph Farington, who described Wells in 1803 as "a West Indian of large fortune, a man of very gentlemanly manners, but so much a man of colour as to be little removed from a negro."

Nevertheless, he was able to rise through society to such an extent that he became Britain's first black high sheriff and only the second black man to hold a commission in the British Army.

When Wells' father died in 1794, he inherited a fortune estimated at £200,000, much of which he used to purchase his Piercefield House estate, as well as contributing generously to a fund to construct the distinctive octagonal tower on his parish church of St Arvans.

He was said to have been a firm but fair justice of the peace, sitting in judgement over white people.

St Kitts and Nevis were governed as different states until they were unified by Britain in the late 19th century

Yet his benevolence in Wales seems to have been in stark contrast to his attitude towards his fellow slaves in St Kitts.

Upon inheriting his father's estates, Wells only freed a handful of his mother's relatives.

In the 1820s, his estate managers were also strongly criticised by abolitionists for exceeding the maximum 39 lashes punishment they were allowed to dole out to slaves.

Yet, perhaps tellingly, Wells himself intervened to prevent a critical report on this from being suppressed.

Dr Draper said: "Wells relied on his enslaved people for his fortune. But at the same time you have to ask what else he could have done beyond simply selling out.

"On larger islands like Jamaica, freed slaves could survive as subsistence farmers, but on islands like St Kitts there simply weren't the social or economic structures in place to allow them to survive independently, enslaved people were utterly tied to the plantations.

"Even slave-owners who were queasy about slavery were very reluctant to take steps they saw as disruptive of the settled order of a slave society. Instead they depended on the British state to provide an overall solution - including compensation for the slave-owners, which Wells himself also received."

Wells' vast fortune, including Piercefield House, was divided among his 20 children

After his death in 1852, his estate was divided between the 10 children of his first marriage to Harriet Este, and the 10 from his second marriage to Esther Owen.

"You can see how the way he chose to settle his estate dissipated that vast wealth quite quickly," Dr Draper said.

"But fortunes such as this fed back into society and laid the foundations for canal-building, the railways and ultimately the Industrial Revolution."

Chepstow Racecourse sits on his old Piercefield estate.

Perhaps the biggest testament to both the way in which Wells "fitted-in", and of the age in which he lived can be found on his memorial at St Arvans Church.

It simply describes him as "a Magistrate and Deputy Lieutenant", making no mention of either his slave heritage or ownership.