How is the Welsh language being preserved in Patagonia?

- Published

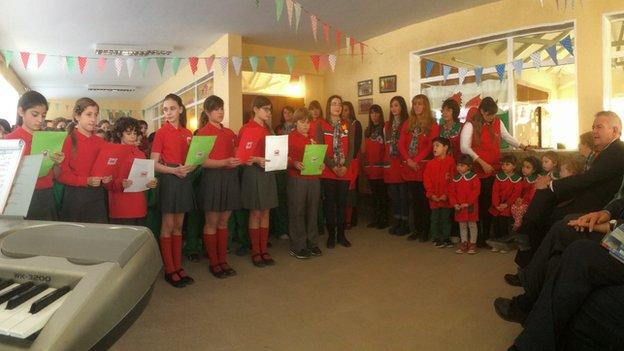

Carwyn Jones sings along to 'Sosban Fach' with children at Ysgol Yr Hendre in Trelew, Patagonia

A gaggle of five-year-olds sits cross-legged on the floor, as Welsh language teacher Eluned Jones holds out a box containing lurid plastic fruits.

The children each take one and, with the help of prompt cards, shout out the colours - "gwyrdd!", "coch!", "porffor!" [green, red, purple]

It's just like an ordinary morning of classes, but there is something that doesn't quite fit.

The view from the window of this tiny school is not of rolling green Welsh mountains, but of the snow-capped Andes - we are not in Wales, but nearly 8,000 miles (13,000 km) away in Trevelin, Patagonia.

As Wales and Argentina mark the 150th anniversary of the arrival of Welsh settlers in Patagonia - when 153 people sailed across the Atlantic to set up a colony - many surviving aspects of the old culture will be celebrated.

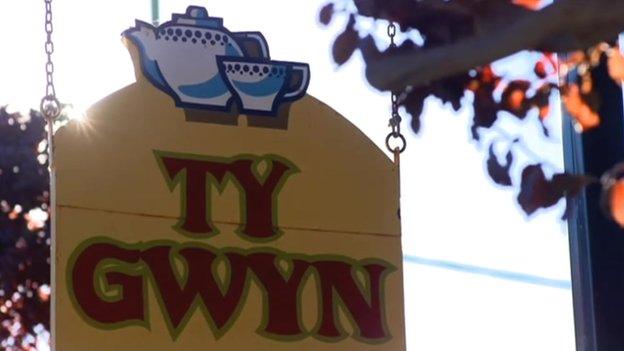

Welsh chapels, choirs, tea houses and annual eisteddfodau still exist in these small communities in Chubut province, such as Gaiman and Trelew on the Atlantic side of the country or Esquel and Trevelin, 400 miles (600 km) west at the foot of the Andes.

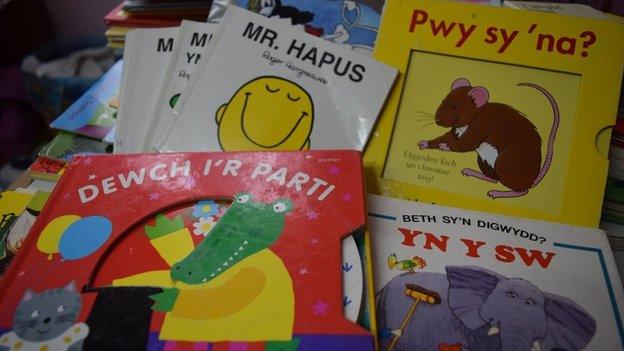

Welsh is part of the curriculum in some schools in the region

But it is the extent to which the language has survived, with more than 5,000 people estimated to speak it, that gives people significant pride.

And in recent years Welsh language learning has not only existed, but grown - including many new students who are not among the 50,000 or so Patagonians with Welsh ancestry.

Liliana Carballo, 57, originally from Buenos Aires, is descended from Spaniards who came to Argentina in the 1600s. Yet, as a lover of languages, she was drawn to learning Welsh, and teaches it in Esquel.

"Welsh is a community language here. You cannot explain why you love something, you just do," she says.

Her 16-year-old pupil Michael is of English heritage but is learning Welsh.

"People aren't studying Welsh because they think they will find a job from it. It's more of a cultural thing," he says.

"My friends find it funny - they call it a dead language. But it would be a pity if it died out. For any culture that would be a big loss.

"It's incredible to think the language has lived so long. It deteriorated, then came back stronger," adds Eluned Jones, a retired primary head teacher from Boncath, in Ceredigion.

Lillian Carballo teaches Welsh in the town of Esquel

Eluned, 57, has travelled to Patagonia for the second year running, to work on a British Council Wales project that promotes and develops the Welsh language in Patagonia.

The Welsh Language Project (WLP) - also funded by the Welsh government and Wales-Argentina Society - has sent three teachers each year since 1997. They teach Welsh from nursery level through to adult learners, using formal lessons and cultural activities.

Welsh language learners in Chubut increased by 19% between 2014 and 2015, rising from 985 to 1,174 - the highest in the history of the project.

And there are now two government-registered bilingual Welsh-Spanish primary schools in the province, with plans for a third by 2016.

Student Michael, 16, says learning Welsh is "a cultural thing"

Some Argentine parents, with no Welsh connections, have even begun sending their children to these schools because they see the intellectual advantages of being bilingual.

They want their children to be culturally aware, or they simply prefer the values and standards of education on offer, says Gareth Kiff, WLP monitor and chairman.

He added: "Learning Welsh has no real financial value in Argentina but people learn it because they see it as something which belongs to their shared past, regardless of their ethnic background."

Two bilingual schools in Patagonia dedicate equal time to Welsh and Spanish

Until the third generation of settlers, speaking Welsh as a first language was relatively common in Patagonia.

But from the 1930s it was mainly restricted to the home and chapel after the Argentine government changed its previously relaxed attitude to having a multilingual nation.

Things took a darker turn during its period of military dictatorship in the 1970s and 80s, when people were banned from giving their children Welsh names.

Welsh Patagonians born in that era often remember grandparents, and sometimes parents, speaking Welsh in the home. And many would still be exposed to the language at the chapel choir or events including eisteddfodau.

But as it became more undesirable to outwardly display their heritage, parents often opted not to pass the language to their children.

Fabio Lewis and his wife Ann-Marie are teaching in Patagonia, while their children Ifan and Miriam are attending local schools

That was the case for Welsh teacher Fabio Lewis, 40, who grew up in Dolavon. His great-great grandparents, Lewis and Rachel Davies, came to Argentina from Aberystwyth, Ceredigion, on the first ship of settlers in 1865, while his paternal ancestors came in 1874 from the Rhondda valley.

"My grandmother's first language was Welsh. She came to live with us and insisted on speaking it. I was always hearing about the dreamland of Wales and how everything was so hard here. She had never been to Wales.

"My parents didn't pass on the language to us but would sometimes turn to Welsh to discuss something they didn't want us to know. Welsh was always in the air."

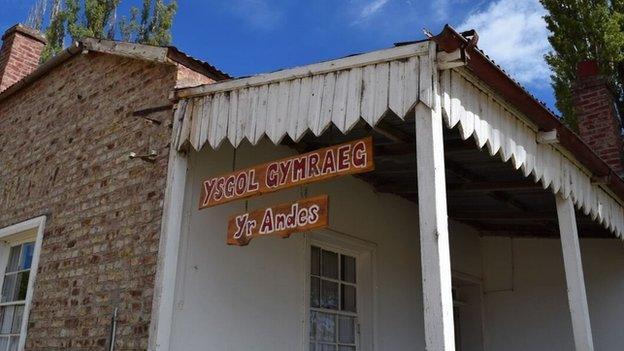

Welsh school Ysgol Gymraeg Yr Andes is in the town of Trevelin

Fabio's later conversion to all things Welsh was embraced with the enthusiasm of the rebellious teenage convert.

He chose to start learning Welsh at 17 and later became fluent. He was helping out at Welsh language classes in Trelew in 2001 when he met his future wife, Ann-Marie, who had come to Patagonia from her home near Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, as part of that year's teaching contingent.

A year they moved back to Wales and got married. They now have two children - Ifan, seven, and Miriam, three - and both worked at Welsh comprehensive schools in Carmarthen until earlier this year.

To coincide with the 150th anniversary celebrations, the couple decided to return to Patagonia with the WLP, and are teaching in Gaiman, Trelew and Dolavon, until December.

"We can quite happily live in a little Welsh bubble here," said Ann-Marie, 42.

- Published30 July 2015

- Published28 July 2015

- Published28 July 2015

- Published30 July 2015