Veterans who return from war but cannot escape its horrors

- Published

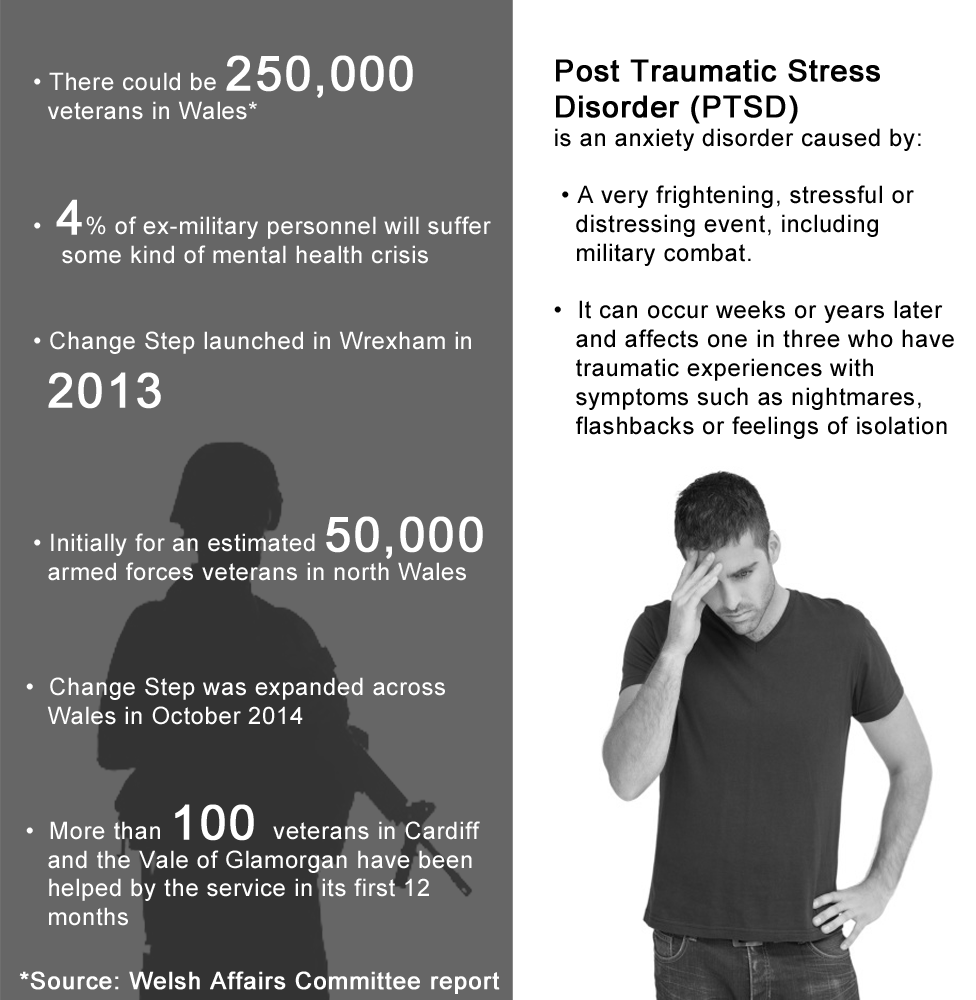

A support service for military veterans with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been rolled out across Wales.

Change Step - started in 2012 by Llandudno-based drug and alcohol charity CAIS - uses former service personnel to help others with mental health issues, loneliness, welfare or addiction problems.

Some of those veterans spoke openly to BBC Wales about the experiences that caused their PTSD and how the service is helping them come to terms with it.

Whether being in the armed forces gives a person something or just takes part of them away is unclear, according to veteran Dave Ireland.

But he said he now realises the experience changes a person forever and can make it very hard to engage with normal civilians again.

This is something he did not fully understand for much of the 22 years since he left the Queen's Dragoon Guards, when he led what he believed was a relatively normal life.

But in 2012, after a "blazing row", he "ceased to be able to function", had a breakdown and made a "concerted suicide attempt".

Mr Ireland now links this to his involvement in one of the bloodiest episodes of the 1991 Gulf War - the so-called Highway of Death - when Saddam Hussein's forces were "obliterated" as they retreated from Kuwait.

While his own recovery was "capped" in December 2014, when he was appointed peer mentor for the charity Change Step, he knows there are many others suffering as he did.

A year on, he is using his experiences to help about 100 veterans from Cardiff and the Vale of Glamorgan who suffer from PTSD.

Many of these have had drug or alcohol issues and will never leave the care system.

"There were always episodes, but I put them down to working and partying too hard," said the 47-year-old from Pontypridd.

"But after a blazing row, I ceased to be able to function. I couldn't stop crying or string a sentence together.

"My head was so full up, I couldn't process the simplest piece of information and just wanted to end it. I was at rock bottom."

As a veteran, he gained help from the Royal British Legion and was not only diagnosed with PTSD, but bipolar.

This was a disorder doctors said he always possessed the chemical imbalance to develop, with it triggered by a traumatic experience.

Mr Ireland, who joined up as an 18-year-old, believes the catalyst was a defining incident of the Gulf War.

Dave Ireland said Change Step was not there to give veterans hugs

"As the Iraqis were being driven out of Kuwait, the coalition forces lined up on both sides of the road and attacked them.

"It was just carnage, tanks, vehicles, they ran a gauntlet and obliterated them," said the former corporal.

He was then part of the group tasked with clearing the road after the assault, adding: "It was horrendous, I'd never seen anything like it. I was 22, no 22-year-old should see that."

While he now lives in Cwmaman, near Aberdare, and is able to "disappear up the mountain" with his Welsh Terriers, he knows that for many there is no escape.

'Anger issues'

For Matthew Baskerville, 33, from Newport, he went from job to job - from a supermarket, to welding to a lorry driver - as he tried to find the "buzz" he felt as part of an elite fighting force, faced with regular life-or-death situations.

After joining the Paratrooper Regiment in 2000, he was one of the first ground troops to "clear out" Basra during 2003's Iraq invasion, when he entered through minefields following an air and tank assault.

He then lived in trenches for three months, taking tablets to combat nerve attack agents and needing "eyes in the back of my head" as he conducted foot patrols.

This had a profound effect on him and, after returning to the regiment's base in Colchester, he experienced severe "anger issues".

As he tried to deal with these, Mr Baskerville began smoking cannabis, drinking heavily and getting arrested for fighting in town.

But it was a car accident, in which he smashed his pelvis and damaged his bladder and femur, that landed him in hospital for seven months and ended his army career.

"It may sound bad, but family life wasn't enough for me.

"There's not the level of adrenalin you get from fighting and putting yourself in extreme conditions and life is an anti-climax," he said.

"Some people find their kicks from being a policeman, a fireman or selling things, but it's very hard to find what makes you tick and it wasn't enough for me.

"You get bored, drinking, drugs, prison, constantly trying to find ways to settle."

He was not diagnosed with PTSD until 2014 and 12 years after leaving the army, is now getting his "buzz" helping other veterans through Change Step.

'Not alone'

Geoff Williams (not his real surname), 54, from Monmouth, Monmouthshire, thought he had the perfect life with a wife, a son, two cars and a good NHS job.

"Everything was going well, but I literally went from a professional life to the gutter," he said.

"I was going on complete and utter benders, spending time in psychiatric units and the poisons unit in hospitals for overdoses.

"Friends were asking 'what are you doing?' I was running amuck and lost everything."

While he is starting to find his feet again after six years of counselling, he admits his behaviour was his way of dealing with something he did not understand.

With no history of mental illness in his family, doctors were unable to explain the sudden severe depression and heavy drinking.

It was "a very aware GP" who linked it to his 22 years in the Brigade of Guards, which he joined as a 16-year-old.

He was eventually diagnosed with PTSD and "delayed shock", having suppressed memories of an incident that nearly killed him while on foot patrol in Umm Qasr, Iraq, in 1992.

"We were trying to deter hostile actions when a roadside bomb was triggered as we walked past a checkpoint, killing three members of the unit," he said.

"I was severely injured, fracturing my skull and partially paralysed."

While he is unsure if he will ever make a complete recovery, he added: "My heart goes out to the young veterans who may not be getting a lot of support.

"They just need to know they are not alone."

- Published1 October 2014

- Published2 January 2016

- Published1 October 2014