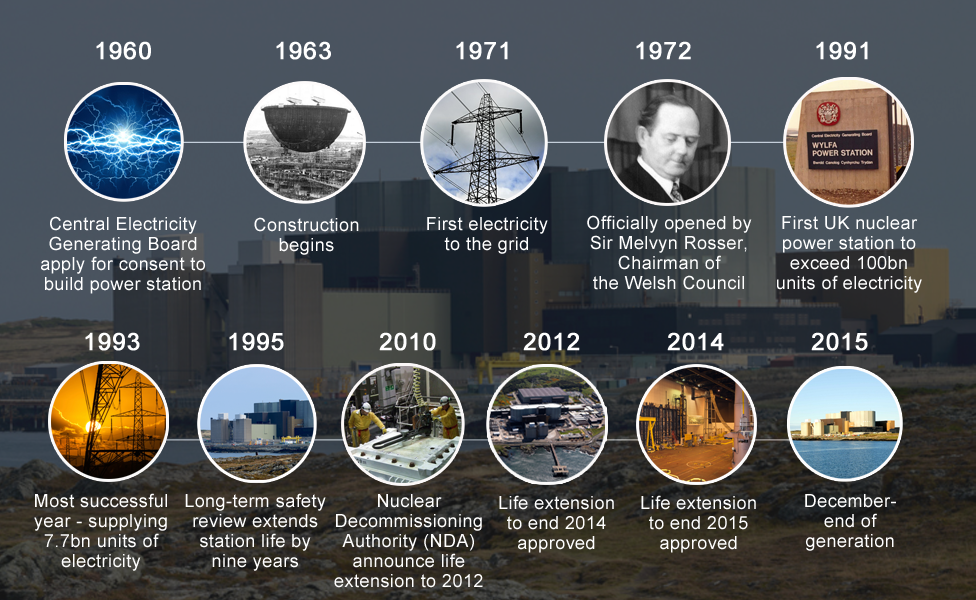

Wylfa: Countdown to shutdown of nuclear power station

- Published

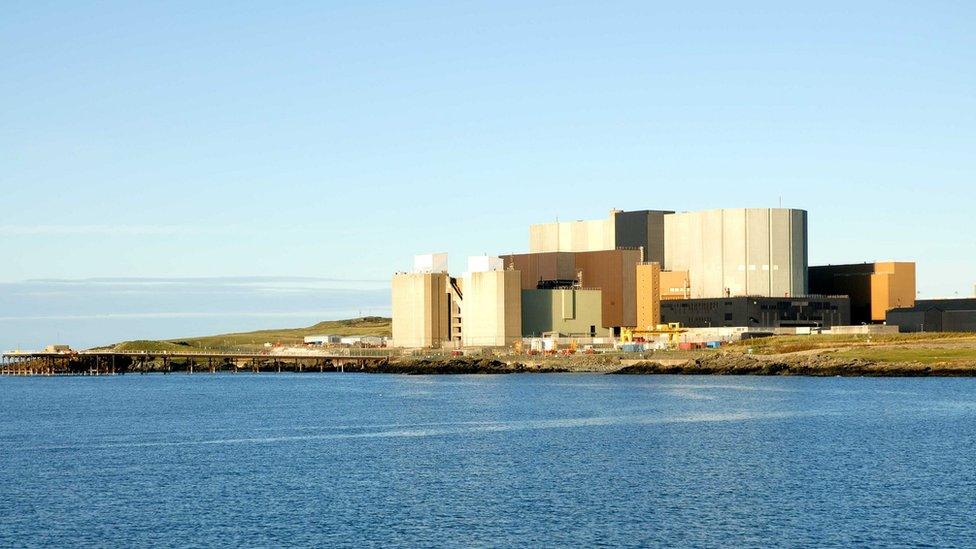

Wylfa nuclear power station will generate its last spark of electricity on 30 December. BBC Wales was allowed inside the plant during its last days of operation to meet some of those who have kept its turbines spinning since 1971.

"I was there at the start - and I'll be here at the end - it's been an absolute joy," said Goronwy Williams.

He joined the workforce at Wylfa nuclear power station in 1965 as it was still being built, an apprentice straight out of school.

Fifty-years on and Mr Williams, or Gron, as he is known by all, has become as much a fixture and fitting at Wylfa as the last remaining Magnox reactor at its beating heart.

Now 66, he is one of the chief engineers who has ultimate say on how Wylfa runs.

And on 30 December he could be the man turning Britain's only operating Magnox reactor off for good.

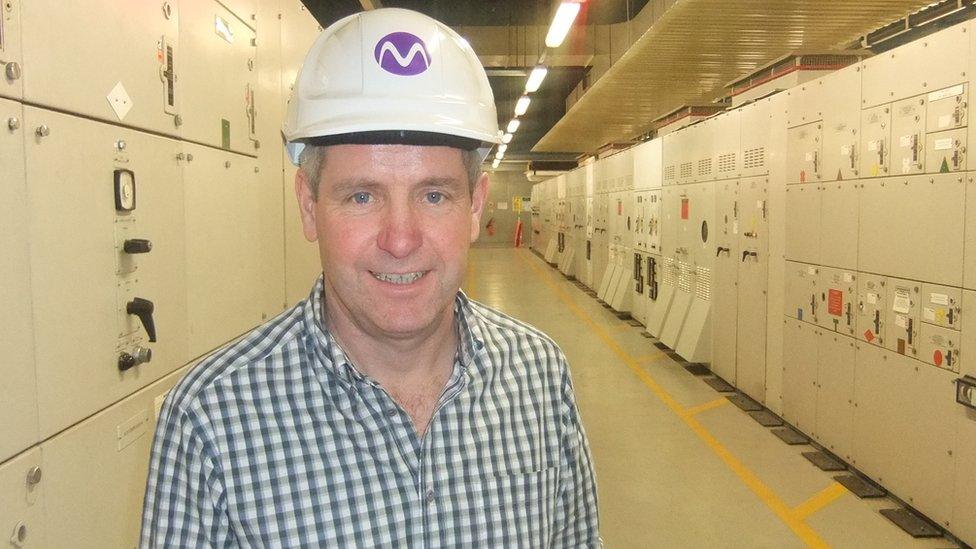

Shift charge engineer Goronwy 'Gron' Williams

"It'll be a sad time, a big change for everybody," he reflected.

"But I'm 66, so that fits in with a big change in my life too."

He - like the nuclear plant and Reactor 1 - is heading towards retirement.

"I've been extremely lucky. I've had so much joy and pleasure from actually running this place.

"To actually shut it down is going to be a sad day."

But what keeps someone at the same site for 50 years?

"Two reasons: the people and the technical challenge," said Mr Williams.

When he first started, straight out of school, he was convinced that he would be at Wylfa for no more than six or seven years.

"At the time, the industry was in its infancy. Our school teachers knew it would be an opportunity for us - but that was the extent of what they knew - it was a new industry.

"But each time I've felt I needed to move away I received a new challenge, and that's how it's been all the way through my working life."

Medwyn Williams, head of projects at Wylfa, Magnox

But Gron Williams is not the only one to spend his entire working life at Wylfa - though relatively speaking, Medwyn Williams is the new boy, he only joined the power station team 35 years ago in 1980.

He is head of projects at Wylfa - projects like making the case to keep reactors running for the last five years - half a decade after the plant should have closed.

"I just have a feeling of being totally proud of what we've achieved here," strained Medwyn Williams, his voice competing with the constant hum of engines pumping carbon-dioxide gas around the reactor vessel, and the sound of whirring giant turbines generating the actual electricity.

"It's been such a safe and reliable site to work on, and then there is just the camaraderie that exists on the site.

"The people make this place so special. It has been a sheer pleasure coming to work every day."

Of course for many at Wylfa, coming to work every day is the "elephant in the room".

By Easter, about 150 of the site staff will be out of a job. Much of the workforce will be contractors decommissioning the plant within three years. And by 2026, nobody will be working at Wylfa.

"Honestly, at this stage I do not know if I'll be fortunate to have continued employment after the generation phase here at Wylfa," Mr Williams said.

"What I do know is that Wylfa has furnished me with an awful lot of skills that are transferable anywhere within this kind of industry. If this door shuts, I'm sure there will be other opportunities out there."

Opportunities like a new Wylfa nuclear power station, perhaps?

On land opposite the current site, diggers are already busy. The area has been undergoing archaeological and geological surveys.

Japanese-owned Horizon Nuclear want to build a new £8bn power station there, using Hitachi's latest generation advanced reactors.

The process of getting the designs for those new reactors - untested in the UK - approved is well under way, and detailed plans for the site could be submitted before the end of 2017.

That is no guarantee of a green light though, as there have been long-established groups on the island loudly opposed to a replacement nuclear plant, since one was first considered way back in 1979.

But Ffion Morris certainly has her eye on the future development.

"Definitely - that is one of my aspirations. I want to come back," she declared.

She is a relative rare breed in the nuclear industry - a woman engineer, in charge of about 150 people at Wylfa, running seven maintenance teams.

"I always knew that I wanted to do something that was technology-based, something that was industrial-based - that was always my aim.

"I was the only female at a certain point within the engineering department at Wylfa, but that has definitely changed."

Ffion Morris, head of maintenance at Wylfa, Magnox

Ms Morris has had almost 10 years at the site, joining after leaving university.

"We've always known that Wylfa was going to shut. It always had that finite lifetime, and that has arrived now.

"It is worrying - it is worrying for the local community and other industries around the area as well."

But, as she noted, those communities, businesses and workers have all known the day was coming, and that knowledge has been a powerful tool.

It has seen more than £4m invested in a project to build the workforce's skills since Reactor 2 at the plant was turned off in 2012.

"Hopefully I can take all the experiences and opportunities that Wylfa's given me over the last 10 years. They've financed my academic career, I've been able to do my Masters [degree] here. So that will enable me to have a brighter future."

But it is certainly the end of days for Wylfa.

And while Wylfa may officially be off-grid and no longer generating power, it won't be forgotten for a very long time.

After decommissioning ends in 2026, the reactor buildings and stores for the Magnox fuel will be left untouched until they are safe to dismantle.

That will be in about 90 years - around 2105.

Wylfa nuclear power station under construction, showing a partial reactor vessel and building work

- Published30 December 2015

- Published30 December 2015

- Published30 December 2015

- Published2 December 2015

- Published7 April 2015

- Published17 February 2015