Maerdy: The day the last pit in the Rhondda closed - 25 years on

- Published

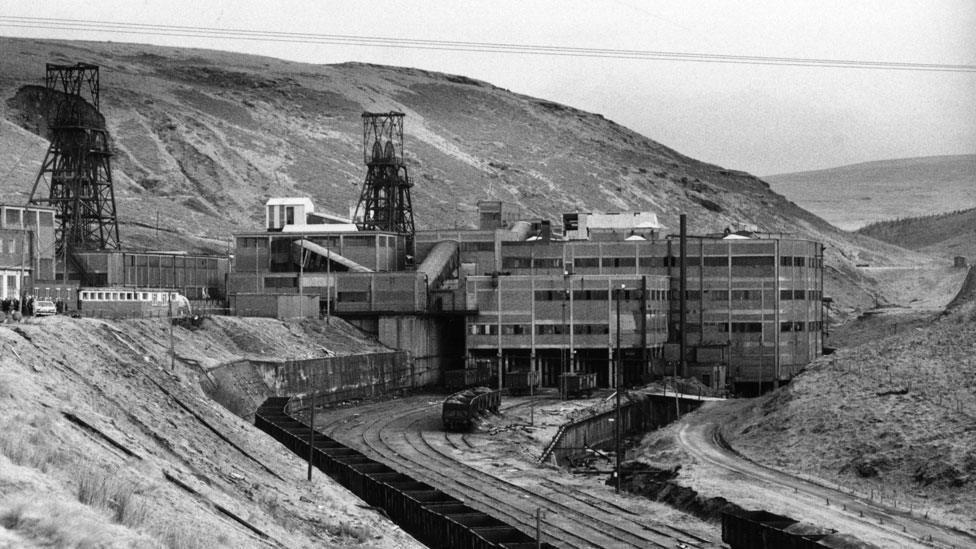

Mardy colliery once stood at the very top of the Rhondda Fach valley

A hundred years ago there were 53 collieries in the Rhondda. By 1990, there was only one left, at Maerdy at the very top of the valley.

The village was once dubbed "Little Moscow" for its militancy between the wars. The striking miners - and their wives - played a prominent role during the year-long strike from 1984.

Mardy Colliery closed 25 years ago today with 300 job losses.

But what happened to the village, and some of the men?

We will be looking at Maerdy's community now and then over three articles.

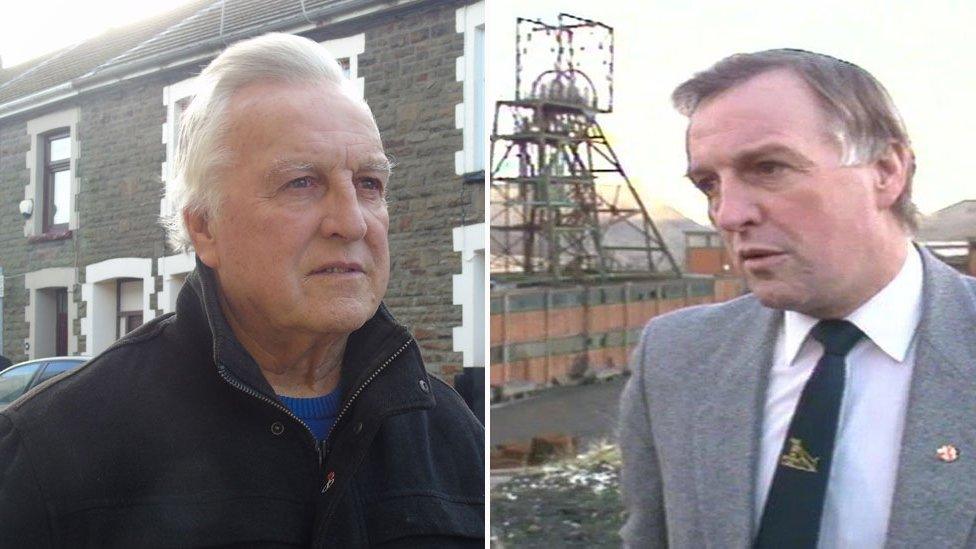

Then and now - Roy Jones worked at Mardy Colliery until the last day

Roy Jones has a link to the mine going back five generations. His uncles worked there and his father had driven a locomotive on the pit surface.

"I worked underground for almost 31 years up to the day it closed," he said.

"On the last day, it was a very emotional day. We had a service in the canteen, a lot of people from the village came up for it - and a couple of my old aunties whose husbands had passed away due to the colliery through pneumoconiosis or injuries.

"The minister Norman Hadfield had worked at Mardy before he was ordained, so that added to the atmosphere and the emotion of the day.

"We had a short service in the park. We all met in the clubs and pubs after. It was worrying but exciting. What was I going to do next? I was 46 at the time but it was more worrying than exciting I think."

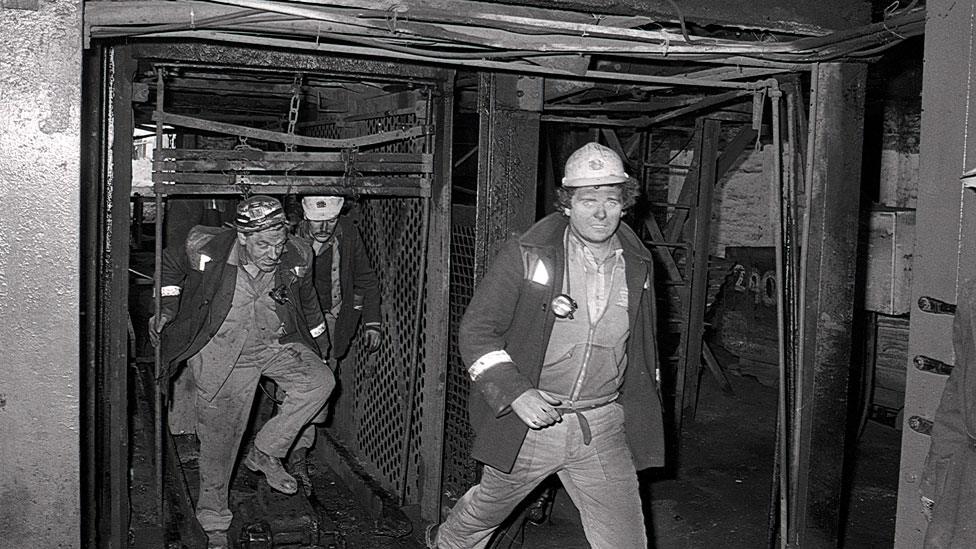

This is how BBC Wales covered the last shift - and the march and service to mark the closure in December 1990

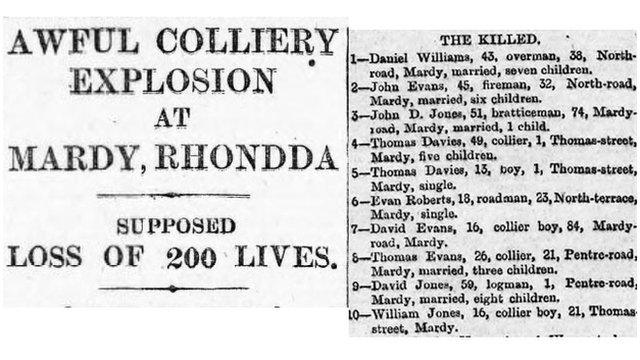

THE CHRISTMAS EVE DISASTER OF 1885

First reports put the death toll as high as 200 but it was soon revised and the lists of the dead - men and boys - started to be published

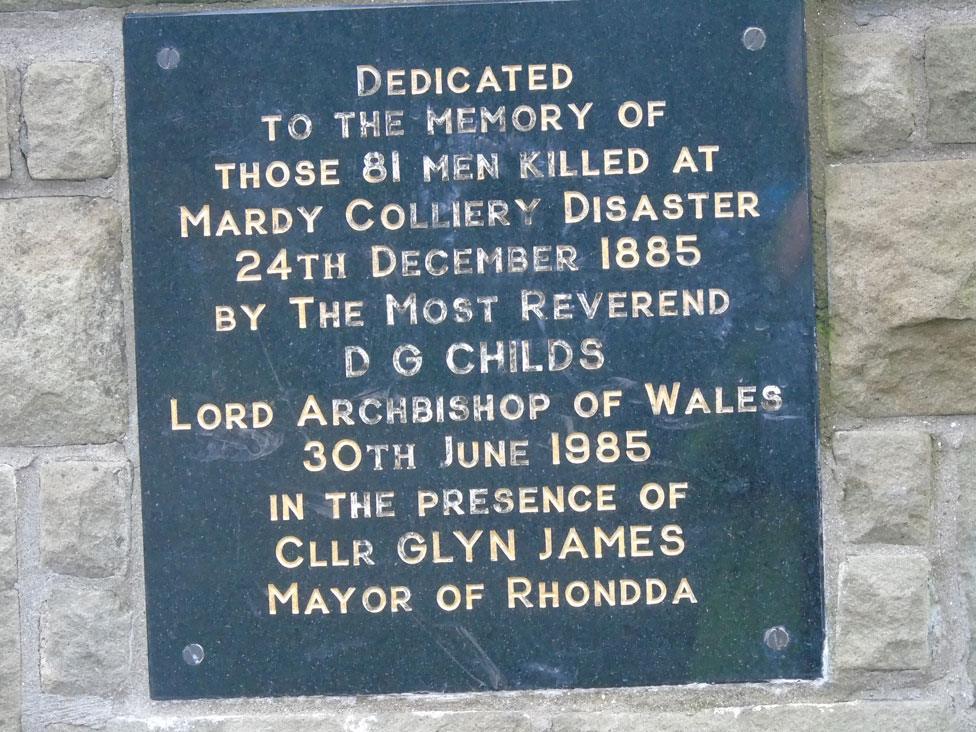

Maerdy is not short of reminders of its mining past. The closure of the pit is marked on one plaque. Close by is a memorial to a more tragic event.

Another, more sombre anniversary, will pass on Christmas Eve - it will be 130 years since an explosion killed 81 men and boys.

Roy's great-grandfather Daniel Williams headed the list of the dead. He left a widow Ann and Roy's grandmother, the youngest of seven children.

Mardy had been open 10 years but there were on average three serious pit accidents or explosions a year across Britain.

On the day shift on 24 December 1885, 750 men and boys were working underground. At 14:40 GMT, a build-up of gas ignited. One survivor recalled hearing the "earth tremble" as the effects of the blast carried on for a mile.

There was no telegraph at Maerdy and it would be 16:00 before the news reached Pontypridd. Most of the bodies were recovered by 07:00 on Christmas Day.

"Women and children were huddled together, some cried and wrung their hands in the wildest despair," said one report.

Daniel Williams was over man at the pit, a position of authority. "A man of great probity and widely esteemed," said his obituary. His funeral was attended by the mine owner's son and his death was the focus of the subsequent inquest.

Although no single cause was identified, the coroner criticised safety procedures, including how dust was allowed to build up.

A memorial to the disaster in the village

Roy and David have been lifelong friends

When Roy was in school, he was a classmate of David "Dai" Owen, and they remain big buddies. They started at Tylorstown until they were transferred to Mardy colliery.

At the end of 1985, David had an accident and was invalided out.

The year-long strike was tough and bitter.

It was over plans to close pits, which the National Coal Board called "uneconomic".

The walk-out in south Wales was almost total and Maerdy became more than symbolic for that rock solid support. There was no need for a picket line at the colliery as they knew no man would try to cross it.

The miners believed they were fighting not just for their livelihoods but the survival of their village of 3,500 people.

Some Maerdy miners found themselves in other parts of the country during the strike.

Roy, now 71, recalls the "battle of Orgreave" in south Yorkshire in June 1984, when as a flying picket he saw bruised and bloodied miners taken in a bus with its seats ripped out to the back of a police station in Rotherham.

The strike ended in defeat and in Maerdy, an emotional but still defiant march back to work.

Not long afterwards, there was a decision to stop bringing coal up from the Mardy pit heads. The colliery was effectively joined up underground with the neighbouring Tower colliery at Hirwaun to make one coalfield from mid 1986.

A few more years of uncertainty followed before the closure was announced.

Recalling the final day, David says: "My heart was with every person that day. It was such a moment in my life, a moment we'll never forget; to see men I started work with marching and when they got to the park, they unveiled the dram [of coal] there and the banner was put up.

"It was an emotional day for every one of us."

David is a keeper of the flame. He is the secretary of the Maerdy Archive, author of 16 books. He has also worked with Rhondda Heritage Park to preserve miners' lodge banners.

David Owen in the lamp room in 1980

He is quite a character too. A photo of him in the pit lamp room points to his love of Elvis Presley. He cleaned out his post office savings in 1972 to see The King perform in Las Vegas, and he and other British fans were given the VIP treatment by Presley's famous manager, Colonel Parker.

He has an Elvis plate on his car and is a deacon at the village's Baptist chapel.

He devotes himself to keeping the village and its mining heritage alive.

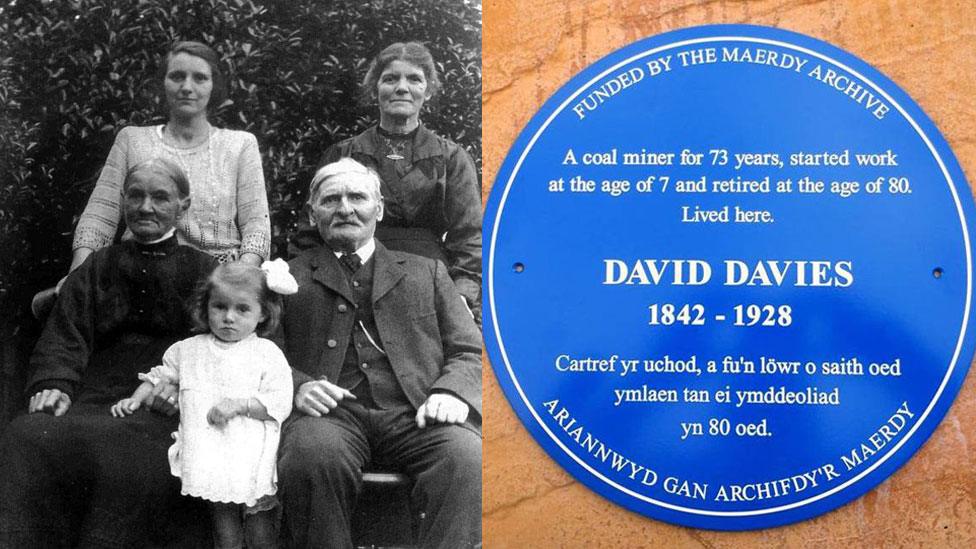

Record-breaking David Davies with his wife of more than 60 years, Elizabeth

There is a blue plaque to David Davies, who was a coal miner for an astonishing 73 years - from the age of seven until he retired from Mardy Colliery as chief engineer aged 80.

The father of 11 - who taught himself to read and write - still managed six years retirement with a pension of free coal until his death in 1928.

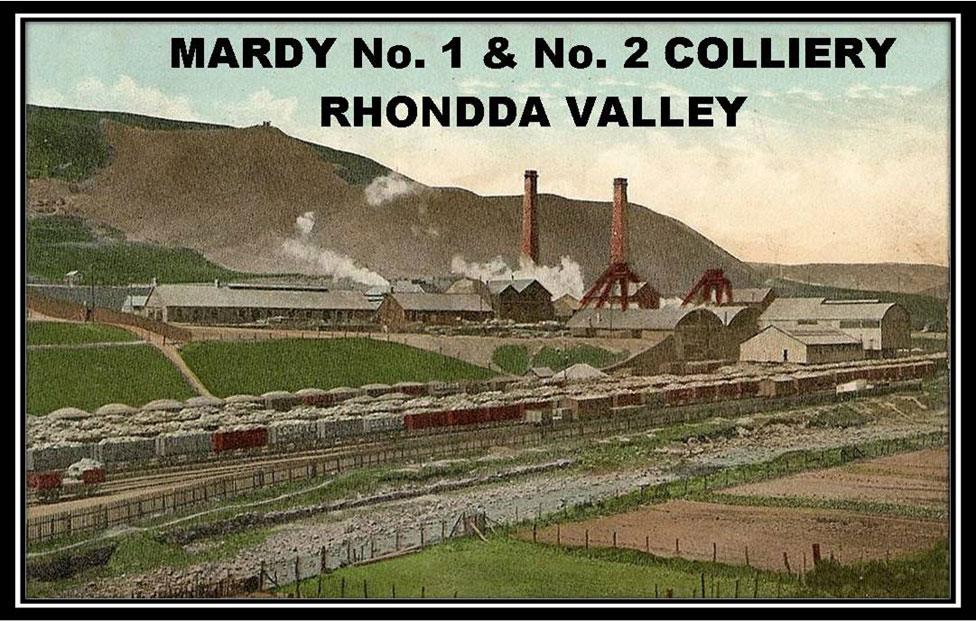

Mardy No 1 and No 2 colliery as it looked in 1929

Maerdy village from the mountain road

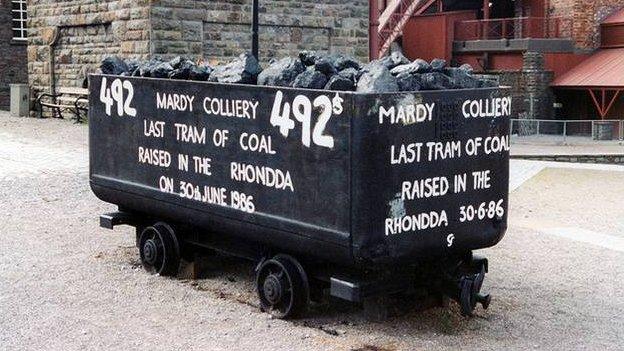

A dram of coal is now part of a memorial feature in the village park. The last coal from Mardy is now at Rhondda Heritage Park mining museum

The pit sheave from Mardy is now the centrepiece of the memorial

David's proudest achievement though is the memorial, made out of the pithead wheel - or sheave - as you arrive into Maerdy.

The wheel had been in two pieces in a council compound since the early 1990s.

The memorial opened in January on the mountain road after a three-year fund-raising campaign.

It tells the story of Mardy colliery's history and its tragedies on huge boards. The foundation stones and plaques of the now demolished Maerdy Workmen's Hall surround it.

"It's for all the miners who've suffered in the coal industry in south Wales," he said. "There were so many deaths through explosions, through dust, through working up to their knees in water.

"There were women and children in those days. A six-year-old child being killed in a colliery. I had to do a memorial to that."

David tells one story, which local children are always fascinated by.

"After the explosion, when the rescuers went down, they came to the air doors underground and there was a little boy who had been working there," he said.

"When they moved his body, they found his little dog under him and his dog was called Try and he'd tried to save him from the explosion.

"We're bringing things to a new generation to show what coal was and what it's done to the villages of the Rhondda, including Maerdy."

In 1984, Ivor England described his family connection to the mine

The BBC made three documentaries about Mardy Colliery. The first was screened in 1984, by then a few months into the strike, and is especially evocative in showing life underground.

There is no actor's voice supplying a narrative; the miners tell their own stories, and then there is the noise, the banter, the work in cramped conditions. It is visceral. A second covered the strike and the third saw a return to the village for the final weeks of the pit in 1990.

Secretary of the NUM Lodge during the strike, Ivor England was at Mardy for 29 years. He played the trombone in the colliery band, including during the march back to work in 1985.

"Mining was sometimes grim and there could be tragedy - and I knew men who died - but there was friendship, tremendous humour and banter."

After redundancy, he became involved in setting up Rhondda Heritage Park and still brings mining history to schools.

"Kids love the history of their area - what their fathers and grandfathers did, they cherish it and it's important."

THE END OF AN ERA

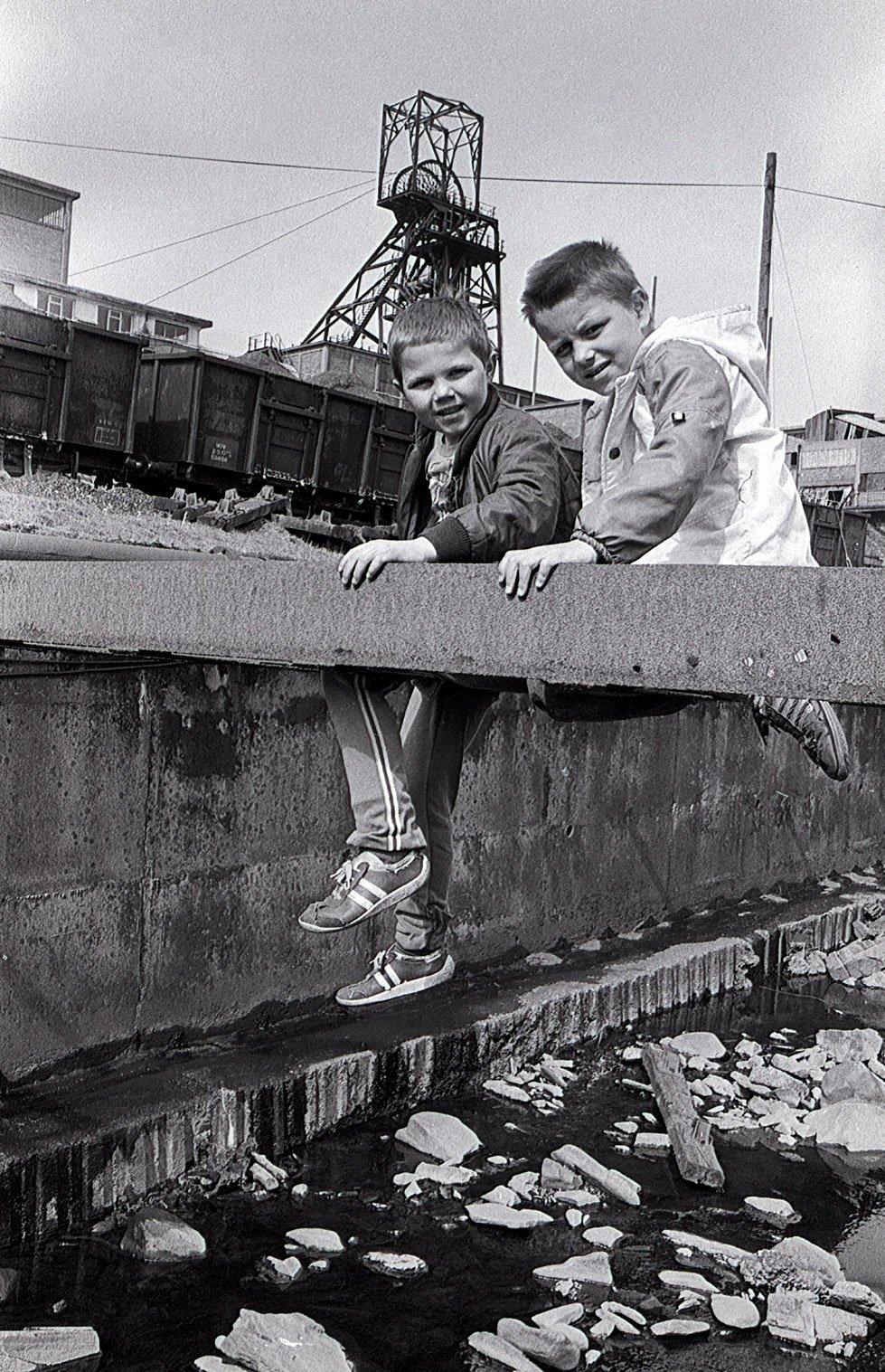

Valleys-born photographer Roger Tiley was at Maerdy during the strike and returned in the weeks before it closed. 'The strike had left the men drained - no-one expected the collieries would be shutting so soon afterwards but they closed one by one'

'I think we all thought the colliery had possibly 10 more years - it was very harsh how suddenly it happened, the Maerdy community was devastated.'

'I've photographed workers in different industries but there was a special bond in coal mining that you didn't see anywhere else,' said Roger Tiley

Children playing near the colliery in the early 1980s - before the strike

The Mardy miners return to work in March 1985 after a bitter year-long strike

A LAST PIECE OF COAL

Families were taken down the mine on the Sunday before it closed

The weekend before it closed, the wives, girlfriends and children of the 300 miners were allowed down the pit and taken on short tours underground.

I went too as a newspaper reporter. By that time, the Mardy pit was linked underground to Tower colliery in the next valley. There were 26 miles of tunnels and men travelled 20 minutes underground by train and walked the rest of the way to reach the coalface. Their journey by the end took well over an hour.

We were taken nowhere near the face obviously but just standing together as the cage dropped 975ft to the bottom and then escorted along the tunnels was an experience you never forget.

It was a day of mixed emotions for the families, as we all gathered in the pit canteen afterwards and were each given a souvenir piece of coal. My piece was put in a paper bag, and inevitably, when I came across it again a few years ago, it had crumbled to dust.

Back in 1990, miner Bryn Davies and his wife Olivia contemplated the colliery's closure

AFTER THE PIT, WHAT NEXT?

Bryn Davies and his wife Olivia were featured in the final BBC programme. Back then, Bryn was 40 with children. He had worked in the pit for 22 years and the couple were contemplating what the future would bring.

Looking back, he says: "It shook us all really. We were all down in the mouth, we had no jobs to go to and the place was getting run down so bad. The valleys today, there's not a lot here, there's no work. The government pulled us right down.

"A lot of families broke up through it. They've split from their wives, they've been used to working hard. Some had money they never had before and went onto the drink. Some did well. Most of the boys would have rather have kept the pits open than everything shutting, even though the conditions were bad."

Bryn Davies now behind the bar of the Ferndale Imperial Club

Bryn considered lorry driving but it would take him away from his family, but by March he and his wife had a chance of taking over a pub, the Ferndale Hotel two miles away.

"For the first three to four months it just about broke my heart - behind the bar serving other people, it was really hard for me. The wife was fine, she'd done it before and was the main one that kept it going and we built it up and kept it going. You've just got to move on with life."

"We were down there for 12 years and then had a chance to come and work here at the Ferndale Imperial Club and thought it would be a lot better, and we've been here ever since. I'm thinking of retiring - I'm 65 now. I was one of the lucky ones."

Mike Richards - now and on the day the pit closed

NUM Lodge chairman Mike Richards did not work again.

"I was 52, too young to finish work and too old to get a job. I'd only done mining. Although I'd done the full service the redundancy wasn't sufficient.

"People were struggling outside to get jobs anyway. If you want to get a job, the most important thing to have is a car and I don't drive.

"Maerdy and the valleys are off the beaten track. When you're talking about any big industry, the future's bleak. We need an increase in factories here - proper jobs. The school's doing a tremendous amount but whatever qualifications you get, you're going to have to leave the valley to get jobs."

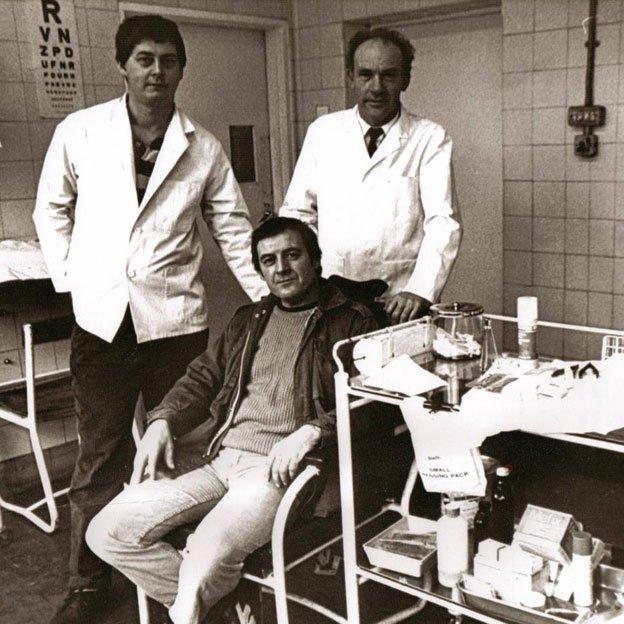

Roy Jones (left) in the mine's medical centre

By the time the pit closed, Roy Jones was working as a first aider there.

"I was one of the rescuers in Aberfan [the disaster in 1966 when a coal tip slid onto the village school, killing 116 pupils] and that was one of the biggest influences of my life so I started doing first aid underground and I trained for the medical centre.

"I got a job as a nursing auxiliary at Llwynypia Hospital for five years and then studied at university and became a qualified nurse and worked in various places, nursing homes as well, and retired about three years ago."

Last Friday, deep mining in the UK came to an end when Kellingley Colliery in north Yorkshire closed.

Ivor England had just returned from a break, meeting old union comrades from other pit communities.

"Looking back, to the men I worked with, the comradeship, I can't have any regrets at all."

- Published23 December 2015

- Published22 December 2015

- Published18 December 2015

- Published24 January 2015