Closure of Kellingley pit brings deep coal mining to an end

- Published

Dan Johnson watched the "end of an era" as the Kellingley miners left after their final shift

Miners at a North Yorkshire colliery have finished their final shifts as the closure of the pit brings an end to centuries of deep coal mining in Britain.

Owner UK Coal said it would oversee the rundown of the Kellingley mine before the site was redeveloped.

Unions said it was a "very sad day" for the country as well as the industry.

The last 450 miners at the pit are to receive severance packages at 12 weeks of average pay.

Many Kellingley Colliery workers clocked off at 12:45 GMT on Friday

The last 450 miners employed at Kellingley Colliery are to receive severance packages at 12 weeks of average pay

Keith Poulson, 55, branch secretary for the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), said: "It has been like being a convicted prisoner on death row.

"We can basically hear the governor coming down the corridor and he's about to put the key in the cell door to take you to meet your fate."

Workers started their final shift at Kellingley early on Friday morning

Keith Poulson has worked in the mining industry for 39 years. He started at South Kirkby Colliery, West Yorkshire, in January 1977 before moving to Kellingley in 1988

Mr Poulson said the workers' morale was "absolutely rock bottom, to be thrown on the industrial scrapheap".

"Since it was announced, I feel like somebody's stuck a pin in me and I'm eventually deflating. I feel completely let down," he said.

Neil Townend, 51, said: "There's a few lads shedding tears, just getting all emotional. It's a bit sad really. I've been here 30 years, I don't know what to expect now, got to get another job."

Stephen Walker, 50, who has worked at Kellingley since 1988, said: "I never thought I'd see this day come but it has, and times move on, and we have to now, and that's that."

"We've lost an entire industry, we've lost a way of life."

'Industrial heritage destroyed'

Nigel Kemp, a miner who has worked at the pit for 32 years, said he would be part of the team capping the shafts his father had sunk in 1959.

He said: "Everything I've had in my life has come from this mine here.

"I wish my dad was here today, because he'd have a lot to say about it. What's happened here is absolutely a travesty."

The closure of Kellingley Colliery in North Yorkshire gives actor Brian Blessed food for thought on a once mighty industry in the north of England

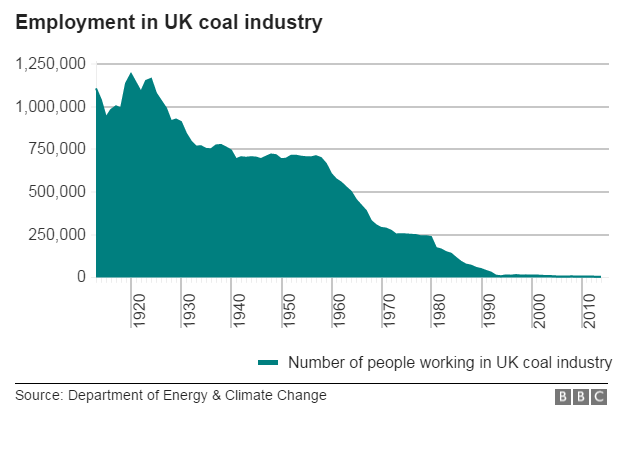

About 250,000 people worked in the UK coal industry in the late 1970s

Mr Kemp said he could hear the miners singing Tom Jones's Delilah on their last journey to the coal face.

The National Union of Mineworkers, which used to have more than 500,000 members, is left with just 100 following the closure of Kellingley.

Miners' memories of Kellingley

Mining machines buried in last deep pit

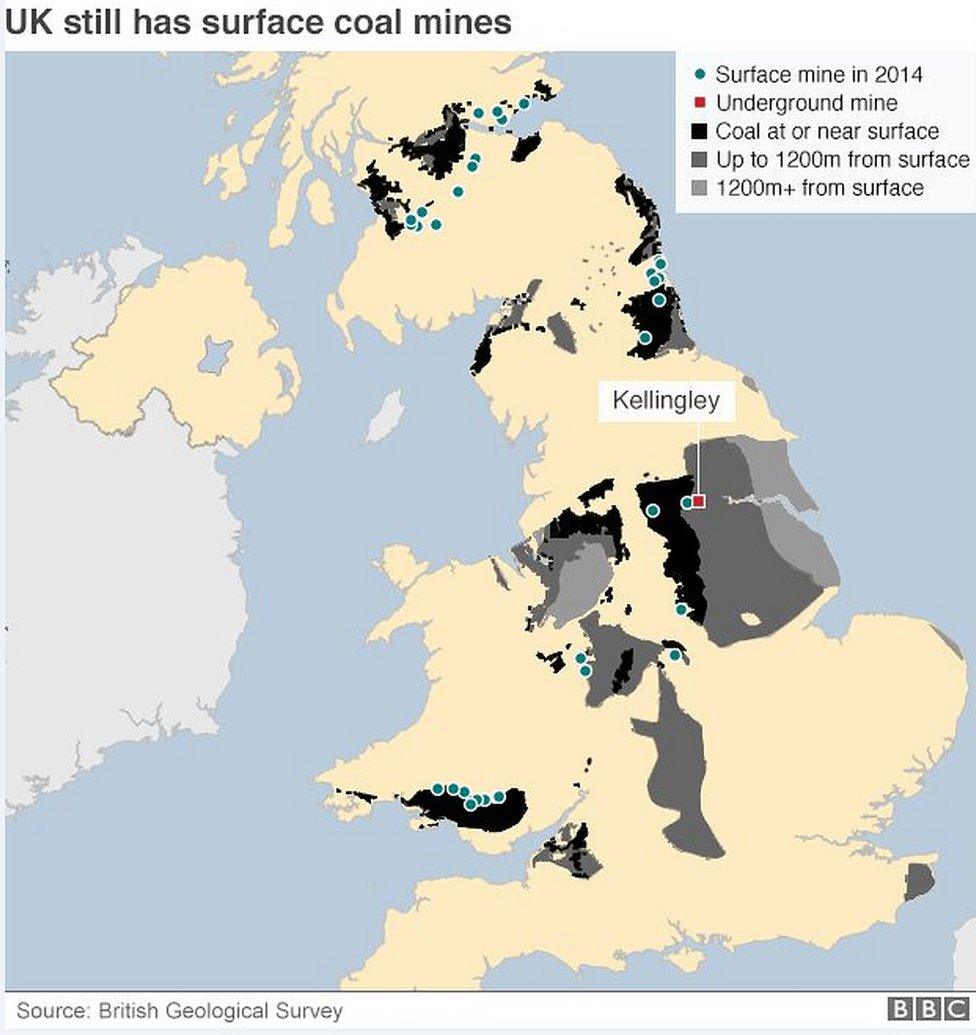

Phil Whitehurst, national officer of the GMB union, said: "The final 450 miners, the last in a long line stretching back for generations, are having to search for new jobs before the shafts that lead down to 30 million tons of untouched coal are sealed with concrete.

"This is a very sad day as our proud industrial heritage is destroyed [by the government]."

In 2014 Michael Fallon, Conservative MP and the then business minister, said: "There is no value-for-money case for a level of investment that would keep the deep mines open beyond this managed wind-down period to autumn 2015."

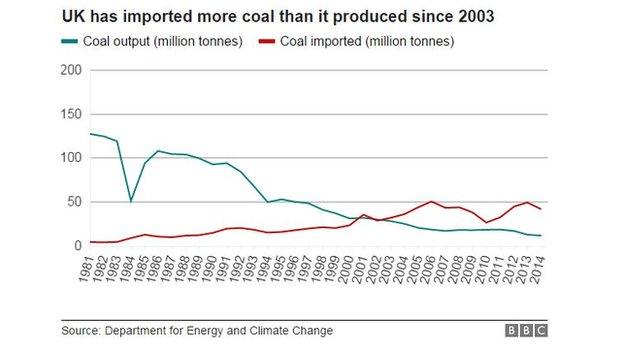

How coal production has fallen

Official figures from the Department for Energy and Climate Change show the UK imported more coal than it produced for the first time in 2001 - a trend repeated every year since 2003.

In 2003 the UK produced 28.28m tonnes and imported 31.89m The graph below shows how output and imports have changed, with the big dip in 1984 due to the miners' strike, external.

UK coal production and imports

Miners at Kellingley are expected to join a march planned to take place on Saturday at nearby Knottingley, West Yorkshire, to mark the closure.

Seventeen miners have lost their lives at the 58-hectare site since production began in April 1965.

A memorial to the dead miners is being transferred from the colliery to the National Coal Mining Museum in Wakefield.

Photographers meet Kellingley staff at their Christmas party

Updates on this story and more from around the region

Known locally as the Big K, the largest deep pit in Europe was hailed as the new generation of coal mining and could bring up to 900 tonnes an hour to the surface.

Kellingley is among the deepest pits of its kind in the world

At its height, Kellingley employed more than 2,000 workers. At the same time, up to 500,000 people were working in the coal industry nationally.

Analysis

Danni Hewson, BBC Look North Business Correspondent

The cold truth is that the way our economy works made the closure of our last coal mines inevitable.

No matter the murmurings of an ideological campaign, market forces are the main axe wielder here.

The US's dash for shale created a glut of cheap imports that Kellingley coal simply couldn't compete against.

But, of course, that's not the whole story. Environmentally, coal could only have had a long-term future if we'd developed and perfected Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), and plans for that were shelved earlier this year. And that's where it does get interesting.

The current government is pushing shale as the potential stop gap, but the industry-backed Task Force on Shale has said gas, like coal, has no real longevity without CCS.

And so the wheel goes round, the UK is perusing a relationship with gas, other countries are still flirting with King Coal - both fossil fuels. All seem to agree that relying on renewables alone is still a somewhat distant dream.

- Published18 December 2015

- Published18 December 2015

- Published18 December 2015

- Published18 December 2015

- Published10 December 2015

- Published10 July 2015

- Published31 January 2015

- Published30 December 2014

- Published10 April 2014