Tragedy after surviving a WW2 shipwreck for 70 days

- Published

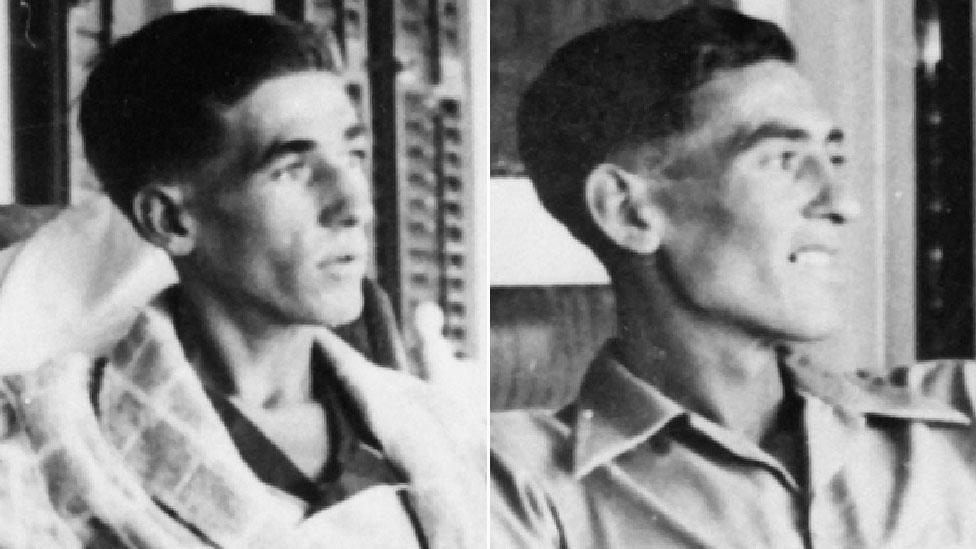

Roy Widdicombe and Bob Tapscott were visited by the Duke and Duchess of Windsor in hospital in Nassau at the end of 1940

Shipwrecked twice, what luck 21-year-old merchant seaman Roy Widdicombe had finally ran out 75 years ago.

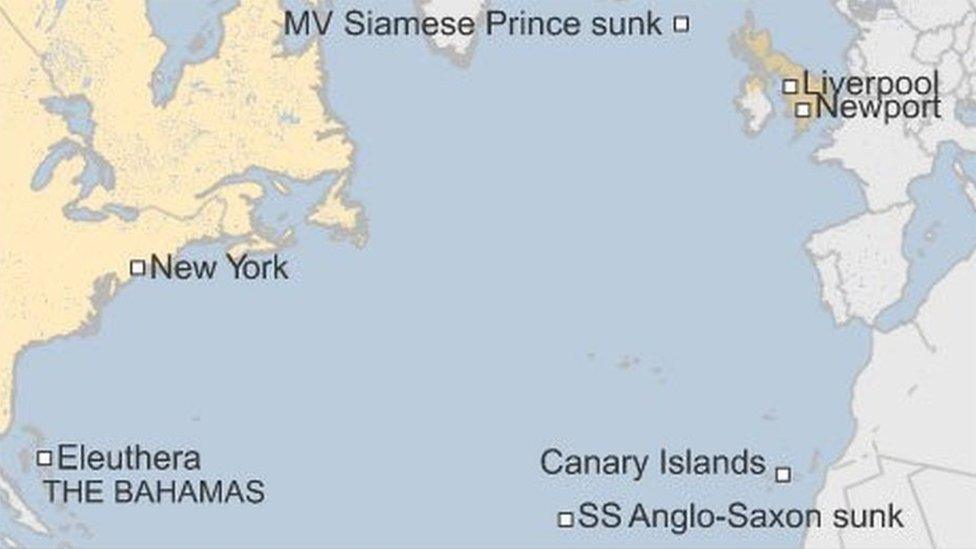

The sailor was heading back to Britain, a VIP passenger on board the cargo ship Siamese Prince, when it was sunk by a U-boat off the coast of Scotland. He died along with 67 crew and other passengers.

It was a fateful twist to an extraordinary World War Two story, which links together two maritime tragedies.

Widdicombe had been on the voyage home to Newport, weeks after he and Cardiff seaman Bob Tapscott rowed for 70 days in a tiny open-top boat after their ship was sunk in the mid Atlantic.

Their skeletal figures had washed up finally on a Bahamas beach after a remarkable and harrowing journey of nearly 2,300 miles (3,700km).

The survivors were greeted as heroes, but sadly there would be no happy ending for either of the young men.

Able seaman

They had been merchant seamen on board the ship Anglo-Saxon, which had left Newport with a crew of 32, many from south Wales.

After the ship's sinking, seven men managed to escape in an open boat in the middle of the Atlantic. But only two would survive the ordeal.

Tapscott was 19 and the youngest of six children. His father and grandfather were ships' pilots in Cardiff. He first went to sea before the war, aged 15, and had sailed to Argentina, Africa and the United States. By the time war was declared he was an able seaman.

Widdicombe had been born in Totnes, Devon, and sailed dinghies from the age of six. Just before he turned 11, he opted to join a training ship instead of taking his place at grammar school and eventually went to sea on passenger trips to the Caribbean and Mediterranean and later on freighters.

In the early days of the war, he spent just over a week in a lifeboat after his ship was lost. He survived another trip to Baltimore carrying scrap metal.

In Newport, he met Cynthia Pitman, and bought the suit for his wedding by bartering American cigarettes in Alicante during the Spanish civil war. They married in April 1940 and bought a house.

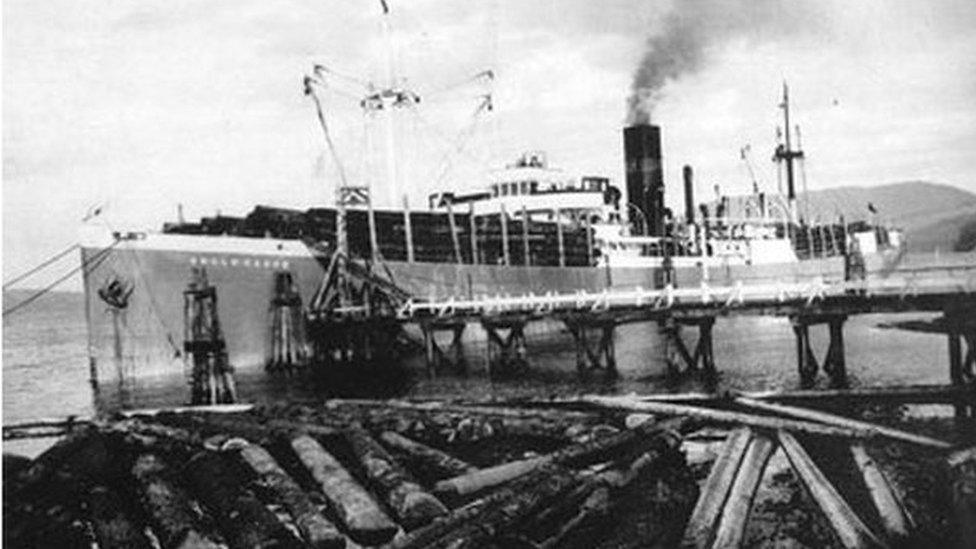

The Anglo-Saxon, in a photo taken by its chief engineer in the 1930s

Then in the July, he joined the Anglo-Saxon.

The ship left Newport on 5 August, loaded with coal with only the captain initially knowing they were bound for Buenos Aires. It was also armed with a naval gun for protection.

By 21 August, the ship was 500 miles (800km) west of the Azores. As Widdicombe began his evening watch in the wheelhouse and Tapscott played cards, the ship was rocked by four explosions and then machine gun fire across the deck.

A German raider, the Widder, was attacking them with shells.

Within minutes, the Anglo-Saxon was ablaze, her captain was dead and lifeboats badly damaged. Within the hour she had sunk.

Widdicombe and Tapscott managed to escape with five others in a jolly boat, the 18ft-long (5m) craft used to ferry crew around at port. Others tried to escape in life rafts but were shot under the orders of the German skipper.

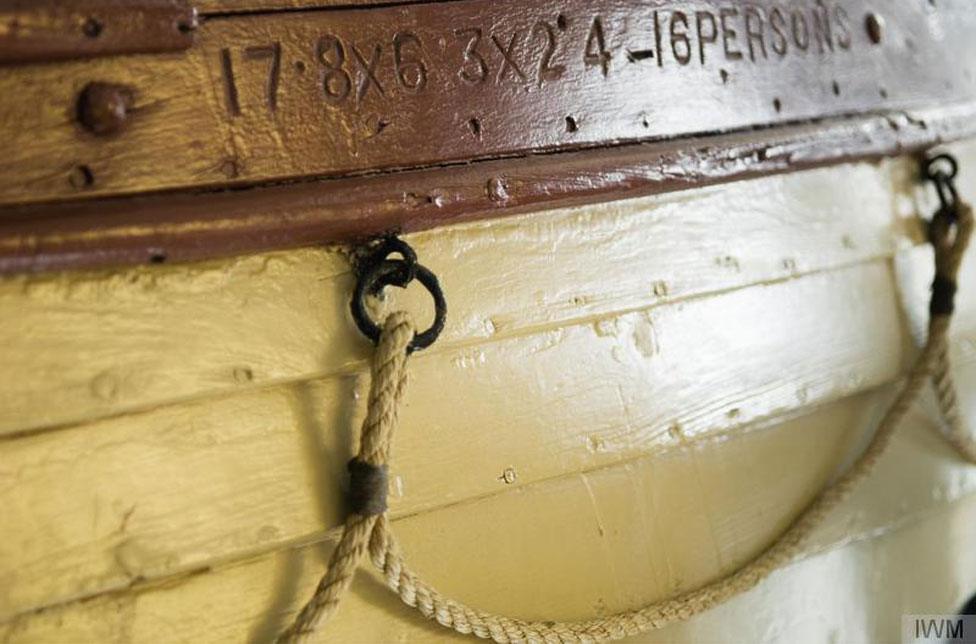

Anglo-Saxon jolly boat

6

oars

4

gallons of water

-

1 sail, compass, rusty axe, razor and oil lamp

-

2 rolls of bandage in medical kit

-

11 tins of condensed milk

-

3 tins of boiled mutton and a tin of ship's biscuit

In darkness, the jolly boat passed close to the enemy raider but the men only started rowing at a safe distance.

Of the seven inside, three had serious injuries.

The men kept to regular watches, strict rations and those fit enough took turns at rowing - with the hope for rescue or landfall within 16 days.

The first night after the wreck they spotted a ship, blacked out, but fearing it was the Widder returning, they were relieved when it passed by.

Four days in, the men were soon getting dehydrated; two of the injured were developing gangrene but Barry Collingwood Denny - keeping a log - reported the men ate a Sunday lunch of tinned mutton "which greatly improved their morale, which is splendid. No signs of giving up hope".

But as time wore on, their rations and water became depleted, they all grew weaker and there was no sign of a rescue.

This is what happened.

THE ORIGINAL SEVEN SURVIVORS:

Roy Hamilton Pilcher, 21, of Godalming, Surrey. "A proper gentleman". Radio operator and 2nd warrant officer he had been asleep when the ship was struck. His foot was injured by gunfire and left completely shattered. Gangrene set in, he grew delirious and the crew considered amputating his foot with the axe as his condition got worse. He was the first to die, on 1 September, the 11th day

Francis Graham Penny, 44, gunner, Royal Marine veteran, from Eastney, Hampshire, married with a son. Good humoured and fitted in well on board the ship. Shot through the right wrist and suffered a shrapnel wound to his hip. He became withdrawn and while steering the boat, decided to go over the side at 1.30pm on 4 September, the 14th day, 700 miles from the sinking site. "Penny, very much weaker, slipped overboard," the log recorded.

Chief Mate, First Officer Barry Collingwood Denny, 31, from Sydenham, south east London. Found the captain dead during the attack on the ship and within six minutes had ordered the men to the boats. He kept a log until 2 September when he grew too weak with serious cramps. "Crew now feeling rather low" was in his final entry. By then, the boat's rudder was lost and they had run out of water. He decides to go over the side and asks "who's coming with me?" He hands his signet ring to Widdicombe to give to his mother before he jumps over the side of the boat on 5 September, the 15th day.

Lionel Henry Hawks, 22, from Sunderland, third engineer. His first sea trip, was said to be afraid of water. He was asleep when the ship was attacked but was in a protected area. He goes over the side with Denny, floating away apparently in each other's arms.

Leslie Morgan, 20, lived near Widdicombe in Lewis Street, Newport, second cook. "Garrulous" and had been listening to the radio when the first shell struck. Flying metal injured his foot. He took to drinking sea water after fresh water ran out and had bouts of delirium. On 9 September - the 19th day - Widdicombe wrote in log: "2nd Cook goes mad; dies. Only two of us left" There are different accounts however - one says he announced "I'll go down the street for a drink" and went over the side, the other that he fell overboard in rough seas.

Roy Widdicombe - prone to mood swings - and Bob Tapscott - a calmer character - were different personalities and there had been some tension between them on the ship, but now they were thrown together. The two survivors.

'GETTING VERY WEAK'

Tapscott and Widdicombe had their own struggles. In the desperate ordeal, both twice decided to end it all over the side of the boat. But times they dragged themselves back inside, unable to accept their fate.

That last aborted attempt heralded a turning point. They took alcohol from the compass and drank it together that evening, laughing and joking. It was followed by their first proper sleep for weeks.

The next day - 12 September - the 22nd day on the boat - it finally started to rain and gave them enough water for the next six days and made swallowing a nibble from their diminishing biscuit ration a little easier.

It rained again on 20 September, two days after their rainwater had run out. But the sun was getting stronger and they were desperately hungry.

"Getting very weak but trusting in God to pull us through," Widdicombe wrote.

The next few days turned into weeks.

They thought they spotted land but it was a mirage. Their first sight of a ship - a large steam liner on the horizon - sped out of reach as they exhausted themselves rowing towards it.

They rode out a violent two-day storm and hit a whale.

By now, they took to chewing ribbons of floating seaweed although it increased their thirst. They took to eating their own peeling skin, shoes and the lining of Pilcher's tobacco pouch.

A flying fish flew into the boat and they sliced it in half with a razor. There were meagre handfuls of tiny crabs but fishing with a hook made from a safety pin proved useless.

By mid October, they could only crawl on all fours and were too weak to stay awake to sail during the night. Both started to suffer in the sun and were covered in small blisters; they had lost up to 80lbs (36kg) each - nearly half their body weight.

A DREAM AND A BEACH

By 27 October 1940, both men were too weak to row.

That night they heard a fish flapping in the bottom of the boat and in the morning they recovered it. It was a Bahamian hound fish and, when they looked up, the pair got their first sight of land.

It was no mirage this time. Within 20 minutes, they grounded on the beach and staggered into the shade on the edge of the bush.

On 30 October, 70 days after being shipwrecked and a journey of 2,275 miles (3660km), they were found by farmer Lewis Johnson and his wife Florence on the island of Eleuthera.

Mrs Johnson had had a premonition they would find something if they went to the beach. They did and returned with a rescue party.

Bob Tapscott and Roy Widdicombe pictured back on the jolly boat during their recovery in Nassau

Barely able to stand, Tapscott and Widdicombe were given coconuts and, soon, beer and bully beef and biscuits. They were taken by truck to the island commissioner's house.

After more food, clean clothes and a shave, they were flown to hospital in Nassau where they spent the next eight days. They had suffered exposure, starvation which brought on pellagra, insomnia and it had taken a huge mental toll, especially on Tapscott.

They started to recover and met the islands' governor, the Duke of Windsor - the former King Edward VIII - and the duchess, Wallace Simpson.

HEADING HOME

By the end of January 1941, Widdicombe was well enough to head home.

At one point, it had looked as if he might have to work his passage back to Britain.

But after some discussions between government departments it was agreed he should be a passenger on the Siamese Prince, a cargo ship carrying beef from New York to Liverpool and "some fuss" should be made of him.

But within a day's sailing British shores, off the Faroe Islands, the ship was hit by two torpedoes from a U-boat. This time there were no survivors.

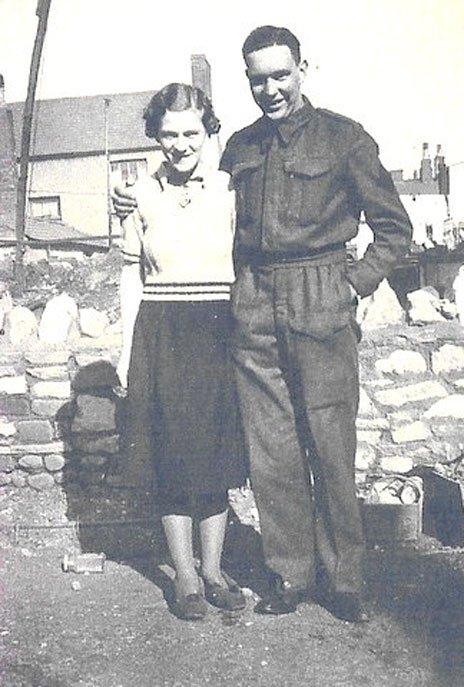

Cynthia, pictured with her brother-in-law George

The trauma for Widdicombe's young bride Cynthia seems unimaginable. She was married for only four months before he left Newport.

Despite hearing in October the Anglo-Saxon "must be presumed lost", she had never given up hope that he was still alive. Then was the joy at his survival.

Arrangements had been made for Cynthia to travel by train to Liverpool to be reunited with her husband. Her bag was packed waiting for the final word, while the bunting was ready in Lewis Street for the welcome home party.

Widdicombe was to have been met off the ship by ministry and naval top brass, "given a good lunch or dinner" before a function involving the Lord Mayor and the press.

"Although the position in which the vessel was sunk was carefully searched, no survivors could be found," says a letter from the Admiralty, expressing great regret.

Cynthia's daughter Sue Irvine, from her second marriage, said nothing had mattered more to her than "seeing my Roy again".

"Even after more than 50 years, mum still became tearful when she recalled the telegram telling her not to go to Liverpool as the Siamese Prince had been torpedoed," she said.

"One other thing I remember her saying is that on the night she was given the news that the Siamese Prince had been sunk she eventually fell asleep but woke very suddenly and, in her words 'Roy was standing at the end of my bed, he was wearing the suit he got married in and he smiled at me. I knew then that he was looking after me.'"

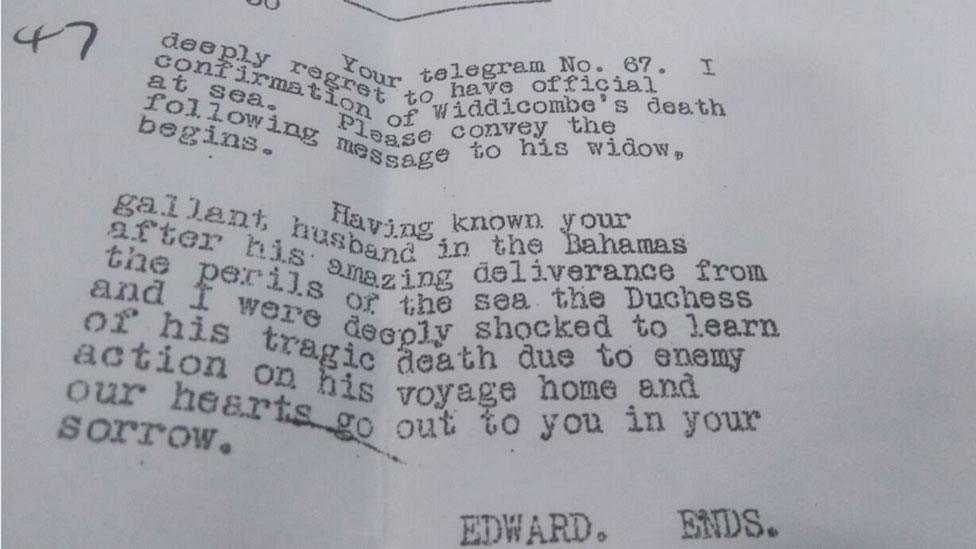

The Duke of Windsor sent a telegram to Cynthia Widdicombe saying he was 'deeply shocked' to learn of the tragedy

Bob Tapscott and Roy Widdicombe

CARRYING A BURDEN

Tapscott stayed in Nassau a little longer before rejoining the war effort with the Canadian Army and the Merchant Navy.

After the war, as now the only Anglo-Saxon survivor, he gave evidence against Helmuth von Ruchteschell, the captain of the Widder, who ordered the shooting of the remaining crew as they escaped in life rafts.

Ruchteschell was sentenced to 10 years in 1947, by a tribunal, as a war criminal and died in custody.

Tapscott returned to Cardiff, he married and had a daughter. But he always carried with him the burden of what happened and suffered depression and symptoms of what would now be recognised as post traumatic stress.

The wartime ordeal was eventually forgotten - at least by the public - and it took him 20 years to even tell those closest to him what had happened.

In 1963, while his wife and daughter were out, he took an overdose of sedatives and a fire started in his home. Despite the rescue efforts of a policeman, he died, aged 42.

Before he took his own life, he wrote a letter to the South Wales Echo newspaper, explaining his actions, which arrived in the editor's office after his death.

To survive was not enough to escape the horrors of war he had experienced.

The jolly boat is displayed at the Imperial War Museum

Notches made on the edge of the boat to mark off the days

A LITTLE BOAT AS A REMINDER

The story of the Anglo-Saxon has been told in three books, one in the weeks after the rescue.

Another was by the late explorer and broadcaster Anthony Smith, who helped bring together relatives of those who died to campaign for the return of the jolly boat to Britain.

American maritime historian J Revell Carr, in the most recent book, wrote: "One must stand in awe and contemplate what happened within the space that this boat represents."

Sue (right) was there to see the jolly boat return with historians J Revell Carr and Anthony Smith and Ted Milburn, whose father Eddie was chief engineer on the Anglo-Saxon

The jolly boat was preserved by Carr's museum but was donated to the Imperial War Museum in London in 1998.

A few months before, Cynthia had died but Sue was there to represent her mother when the boat was unveiled as a centrepiece of an exhibition on the merchant navy.

She said Widdicombe's story gave her mother, suffering from dementia, something to cling to from her long-term memory.

"Her last few months were filled with being able to talk about Roy and what happened, whereas her short term memory loss distressed her," she added.

The jolly boat, as a reminder of that incredible journey and the sacrifice of the men of the merchant fleet, is still on display at the Imperial War Museum.