Cancer lessons for NHS Wales from Denmark

- Published

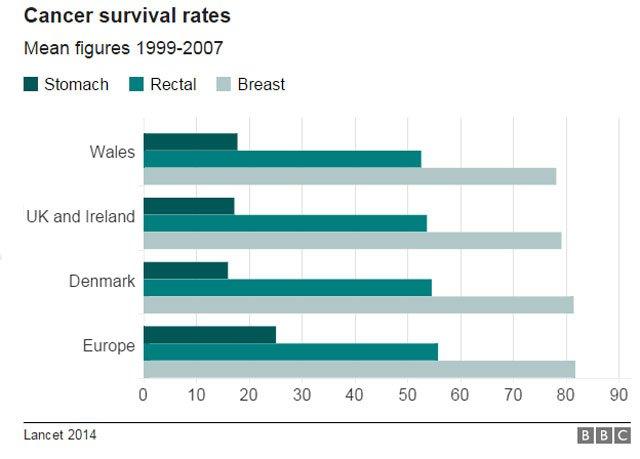

Denmark has improved its cancer survival rates in recent years

Denmark's health service - which is similar to the NHS - started to look in depth at the problem of cancer survival rates in 2000.

It decided to reorganise the way patients were diagnosed by GPs and specialists by bringing in a new approach, especially to deal with those cancer cases which are not initially obvious.

A team of cancer specialists, GPs, NHS and public health experts from Wales have just returned from a fact-finding visit to Aarhus, Denmark's second city.

So what was the problem?

Prof Frede Olesen of Aarhus University said the changes followed "quite alarming" cancer survival statistics more than 15 years ago showing Denmark was performing poorly compared to other European countries, including the rest of Scandinavia.

Part of the problem was that waiting times patients faced before getting diagnosed were too long.

It was not so much the most serious cases where patients came to the GP with obvious symptoms. They could be fast-tracked to specialists in hospital.

It was the cancer cases where patients either had vague or more difficult to diagnose symptoms - or the small number of cancers found in patients who said they were ill but mostly needed a quick test or scan to rule something serious out.

"We looked at 30,000 cancer cases - and more than 25% of all cancer cases were from this group where we didn't think it was something but it suddenly showed as being something and so it's important to find those cases," said Prof Olesen.

Prof Frede Olesen explains how the concept of the Danish diagnostic centres

What were the changes?

The model of care introduced in Denmark has three routes.

First - for patients with " alarm" symptoms of specific cancers - there are fast-track diagnosis and treatment routes with strict time targets.

In addition to that, by law, any patient with a physical illness in Denmark must be investigated within 30 days of a GP referral.

Second, the Danish health service from 2007 set up diagnosis centres - at existing hospitals and clinics - where patients with symptoms which GPs cannot diagnose are given a range of tests and scans quickly to find out what is wrong with them, whether it is cancer or something else.

GP Dr Hanne Heje, who works in Aarhus - a city slightly smaller than Cardiff - said the new system helps doctors who suspect something is wrong but not necessarily cancer.

It also stops the "ping pong" between GPs and different specialists.

"Now we know there's a department meeting the patient with open arms saying 'we welcome you', even though there's not a diagnosis written on their forehead," she said.

Danish GP Dr Hanne Heje explains how the yes-no clinics can turn around one-off tests and scans like X-rays quickly

The third route deals with the group of patients with minor symptoms, which are very unlikely to be cancer but in rare cases could be.

These patients go to so-called "yes-no" centres which offer a simple test or scan so they can be seen quickly and any problems identified.

"This can be solved within hours in some cases but 1% will have a serious disease and this can be detected," said Prof Olesen.

"For these patients before - they might have had to wait four to six months, so for the small percentage where something is found, they'd start treatment six months behind the time schedule."

The results so far

Prof Olesen - a former GP himself - said the changes have not led to a "flooding of the system" by more GP referrals but better organisation of how patients are diagnosed within existing resources.

Importantly, he says it has also led to better survival rates.

"We've got very optimistic results showing Norway, Sweden and Finland are becoming better year by year," he said. "But very clearly in the data Denmark is becoming better, a faster pace than before and catching up and getting closer to where we should be."

Denmark has a similar health system in how it is funded and organised to Wales.

He said there could be lessons shared between Wales and Denmark on how better organisation can help "in catching up the elite in Europe".

Dr Tom Crosby, medical director of the Wales Cancer Network, said he had been impressed with how the Danish health service had broken down the barriers between GPs and specialists to work better together.

He said: "People are not just doing tests in isolation - they are working together to achieve a diagnosis."

- Published11 April 2016