Mametz Wood and the 38th: 'What dark convulsed cacophony'

- Published

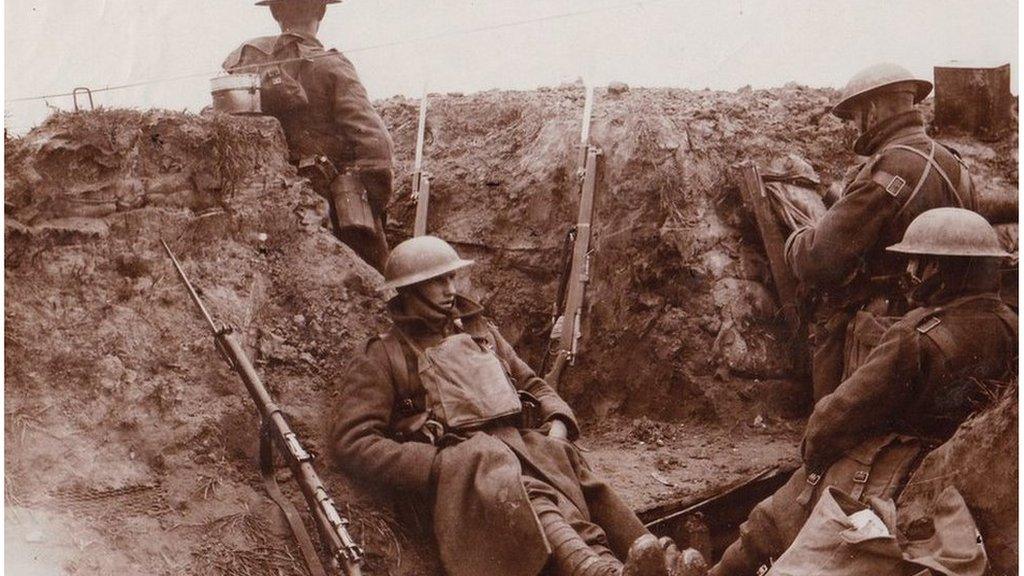

Soldiers of the Royal Welch Fusiliers which played such a vita role in the capture of Mametz Wood, pose for a photograph in their trench

On the eve of the 100th anniversary of the battle of Mametz Wood - the first major offensive of World War One for many Welsh soldiers - memorial services are being held across the country.

The 38th (Welsh) Division paved the way for control of the woodland - nearly a mile wide and more than a mile deep - in northern France. Its capture was of key importance in the Battle of the Somme where Allied forces would fight the Germans on a 15-mile front for five months.

During a bloody five-day battle, 3,993 Welsh soldiers were killed, missing or injured, putting their division out of action for almost a year.

In the first of two written documentaries, Lt Gen Jonathon Riley, late of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, described the events leading up to and during the battle. Here, in the second part, he explores the battle itself and the extraordinary literary legacy of Mametz Wood.

Gen Riley is a former Commander British Forces Iraq and Deputy Commander NATO forces in Afghanistan; now Visiting Professor in War Studies at King's College London and Chairman of the Royal Welch Fusiliers Regimental Trust. Editor of Llewelyn Wyn Griffith's memoir Up to Mametz - and Beyond and author of 17 other books.

Royal Welch Fusiliers rested on 2 July and on the night of 3 July was ordered, with the 2nd Royal Irish Regiment, to move up and secure a line from the south of Mametz Wood to Strip Trench, Wood Trench and the Quadrangle as far as its junction with Bottom Wood Alley.

It was believed that the position was only lightly held. This was not the case and the two battalions withdrew.

They were ordered to mount a formal attack during the night of 4-5 July, in conjunction with the 17th Division.

After a deal of confusion in the dark, the battalion gained its objectives, using once more the new bombing tactics, for the loss of eight killed and 55 wounded.

Battle for Mametz Wood explained

It was here that Siegfried Sassoon won his Military Cross, bringing in a wounded NCO from the German lines under fire. However there was more, as Robert Graves recalled in Goodbye to All That:

Siegfried had then distinguished himself by taking [on 3 July] single-handedly a battalion frontage that the Royal Irish Regiment had failed to take.

He had gone over with bombs in daylight, under covering fire from a couple of rifles, and scared the occupants out.

It was a pointless feat; instead of reporting or signalling for reinforcements he sat down in the German trench and began dozing over a book of poems which he had brought with him.

Some of the atists and writers who served at Mametz l-r clockwise: Siegfried Sassoon (Getty); Frank Richards (RWF Museum); Sir Wynn Powell Wheldon (National Portrait Gallery, London; David Jones; Robert Graves

The colonel [Stockwell] was furious. The attack on Mametz had been delayed for two hours because it was reported that British patrols were still out. "British patrols" were Siegfried and his book of poems.

The bulk of Mametz Wood was, however, still in German hands.

The task of clearing it was now allocated to XIV Corps under Lt Gen Sir Henry Horne.

Horne decided to attack the wood from two directions using two divisions: the 17th Division would attack from the West, out of 1 R.W. Fusiliers' objective, Quadrangle trench at 02:00 on 7 July, to capture Quadrangle Support Trench and Pearl Alley.

If this succeeded, a combined attack on the wood would be mounted by the 17th and 38th (Welsh) Divisions, with 38th (Welsh) Division attacking across open ground from the east out of Caterpillar and Marlborough Woods.

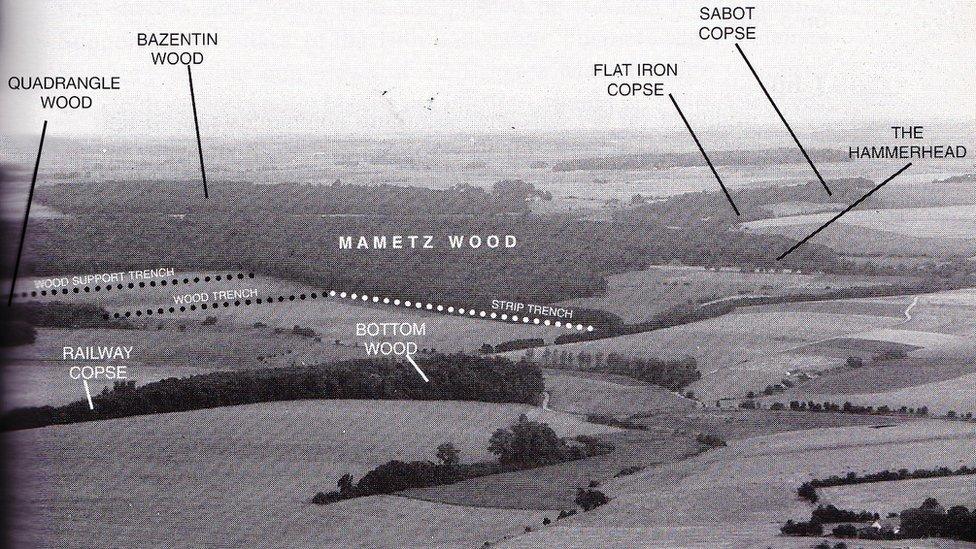

Aerial photographs taken of Mametz Wood in late June 1916 for planning purposes

If the first attack by 17th Division succeeded, the second attack would go in at 08:00; if it did not, there would be an additional 30 minutes of artillery preparation and zero-hour would be 08:30.

At its longest, Mametz Wood was about a mile (1,500m) from north to south and about the same in width. However, about half-way down, its width narrowed to no more than 500 yards and then tapered to a point.

Mametz Wood was a mature deciduous wood, with large trees and very thick undergrowth. It was dissected by a series of lateral rides running east to west and one long vertical ride running south to north.

The other woods around Mametz were smaller, but equally thick, and all were incorporated into the German defence scheme. Between the woods, the slopes were chiefly open meadows typical of chalk down land.

38th Division was to attack in echelon, that is, with the first assault brigade, 115, leading, followed by the second brigade, followed by the third.

The line of assault would take the troops parallel with the German second line trenches and without suppressing artillery fire and a smoke barrage, the troops would be raked by flanking fire from German strong-points in Sabot and Flat Iron copses.

Writer and broadcaster Llewelyn Wyn Griffith from Clwyd. His memoir Up to Mametz was published in 1931. He was a founder-member of the Round Britain Quiz team.

Not long before the start of the Somme battle, Llewelyn Wyn Griffith had been posted as a staff learner to Headquarters 115 Brigade, which consisted of 17th Royal Welch Fusiliers, 10th and 11th South Wales Borderers, 16th and 19th Welch along with a field artillery brigade, machine-gun company, trench mortar battery and a field ambulance company.

The brigade commander, Brig Gen Horatio Evans, was an old soldier not at all in the mould of Price-Davies.

As Wyn Griffith recalled, Evans thought the attack plan was mad.

"The general was cursing last night at his orders," recalled Wynn Griffith in his memoir Up to Mametz.

"He said that only a madman could have issued them. He called the divisional staff a lot of plumbers, herring-gutted at that."

Troops in part of the square-mile of Mametz Wood where at the end of five days, not a single tree was left standing

The first attack by 17th Division failed and so the second phase went in at 08:30.

16th Welch and 11th South Wales Borderers were stopped by heavy machine-gun fire and the attack failed to get within 300 yards of the wood, not least because the supporting artillery fire did not arrive.

A second attempt was made at 11:00 with a similar result.

Wyn Griffith - who was concerned with taking down messages to coordinate movements or resupply or artillery support, and sending them back or forward as required by runners and field telephone - met up with Evans and the Brigade Major, CL Veal, late in the afternoon

"I stood on a step in the side of the trench, studying the country to the east and identifying the various features on the map," he wrote.

A 'slightly injured' soldier returning from battle at Mametz Wood on 7 July 1916

"The thought of the day's torment, doomed, as I thought, from its beginning, to bring no recompense, weighed like a burden of iron."

A third attempt was ordered for 16:30. It had been raining hard all day, the ground was sodden, the trenches half filled with mud and water and the approach to the wood, which was down a slope which in places was almost a cliff had become near-impossible, and all the telephone lines used to call in artillery fire support had been broken.

Gen Evans was convinced that another attack under these conditions would end in disaster.

He had tried to get through to the divisional commander without success, but Wyn Griffith, who had been speaking to an artillery officer, took him to a captured German dugout, where a heavy artillery brigade had established a forward command post.

Here, after a cup of tea, a hard-tack biscuit and some cheese provided by Wyn Griffith from his knapsack, Evans spoke to the divisional headquarters and after some argument, got the operation called off, thus saving many hundreds of lives - but he knew that it had put an end to his career.

"You mark my words," he told Wyn Griffith, "they'll send me home for this. They want butchers not brigadiers... I shall be in England within a month."

He was in fact posted to a home appointment directly after the battle - found wanting in the offensive spirit by the high command, no doubt.

The next afternoon, 113 and 114 Brigades were ordered to attack the wood again on 9 July with 115 Brigade in reserve; this attack was postponed until dawn on 10 July because the conditions had not improved.

At this moment, Major-General Ivor Phillips was removed from command of the 38th Division - a serious decision by Haig and the corps commander who had lost confidence in Phillips's ability to plan and then control a complex operation.

That said, Phillips had been a political appointment based on his Liberal credentials with Lloyd-George, and he had long been resented by many regular officers.

Maj Gen Thomas Pilcher was also removed from command of the 17th Division for similar reasons.

Maj Gen Herbert Watts, from the 7th Division, was moved in to take over temporary command of the 38th Division in the middle of the battle - no easy task at any date, never mind July 1916.

114 and 113 Brigades were ordered to adopt bombing tactics similar to those used by 1 RW Fus - who had been in Watts' division - and move slowly and methodically up the wood.

There would be three lifts of the artillery barrage within the wood.

Commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel Ronald Carden addressed the battalion before the assault

For 45 minutes hour from 04:15, the guns would bombard the southern edge of the wood with smoke. The fire would then lift at 05:00 and the infantry would take the southern edge of the wood, pushing through to the first lateral east-west ride, 113 Brigade on the left and 114 Brigade on the right, the boundary being the long central north-south ride in the wood.

The guns would now be firing on the area beyond the second ride and at 07:00 the fire would then lift again to the north edge of the wood, at 08:15 to the German second-line trenches beyond the Wood.

The artillery fire was to be supplemented by medium machine-gun fire from Marlborough and Caterpillar Woods onto the German communications trenches; while medium and heavy trench mortars suppressed Cliff trench; but remember the earlier point about the infantry having to conform to the supporting fire and not the other way around.

To everyone's astonishment, the attack succeeded.

Coloured handkerchief

113 Brigade was composed of four RW Fus battalions - the 13th, 14th, 15th and 16th. 14th and 16th were to lead. The commanding officer of 16 RW Fus, Lieutenant Colonel Ronald Carden, spoke to the battalion before the assault.

"Make your peace with God," he said. "You are going to take that position, and some of us won't come back - but we are going to take it.'

Tying a coloured handkerchief to his walking-stick he said: "This will show you where I am."

The attack, once in the wood, became a very confused affair not least because of the dense undergrowth and the destruction caused by the artillery.

German soldiers taken prisoner at Mametz Wood: The inexperienced 38th Division were up against the well-trained Lehr Regiment of the Prussian Guard

However, junior officers and NCOs kept a grip on the men and the first ride was reached, with many prisoners taken; the 13th and 15th Battalions were ordered to take over the attack so that at one point there were 11 battalions in the wood.

The 15th got into Wood Trench with the 16th but Wood Support was still held by the Germans; they were bombed out by 13th RW Fus and the artillery fire was shifted to the northern part of the wood.

Although the Germans still held on, by dark, the advance was reported to be within 100 yards of the northern edge of the Wood.

In the evening, 115 Brigade was ordered to relieve the two assault brigades and take over the defence of the wood against German counter-attacks.

Wyn Griffith recorded that Evans and the Brig Maj, CL Veal, went up to the Wood and that he followed slightly later.

'Gory scenes met our gaze'

Soon afterwards, Veal was wounded and Wyn Griffith found himself as acting Brig Maj.

In his book Up to Mametz, Wyn Griffith describes the scene in the wood in some detail: the shattered trees, the bursting shells, the litter of discarded equipment, the mangled corpses of the dead - an experience that stayed with him all his life and came back to him in snatches of nightmare.

Emlyn Davies, who had joined 17th RW Fus with Wyn Griffith's brother Watcyn, later wrote Taffy Went to War.

He said this of the inside of the wood: "Gory scenes met our gaze. Mangled corpses in khaki and in field-grey; dismembered bodies, severed heads and limbs; lumps of torn flesh half way up the tree trunks... Shells of all calibres burst in plenteous continuance; furies of flying machine gun bullets swept from three directions."

David Jones' poem, external is also very largely based on these same horrific scenes

When the shivered rowan fell

you couldn't hear the fall of it.

Barrage with counter-barrage shockt

deprive all several sounds of their identity,

what dark convulsed cacophony

conditions each disparity

and the trembling woods are vortex for the storm;

through which their bodies grope the mazy charnel-ways -

seek to distinguish waling men from walking trees and branchy

moving like a Birnam corpse.

The relief was completed at first light on 11 July.

There was a lot of wild shooting all night, with groups of men firing on one another, mistaking each other for the Germans.

German soldier's overcoat hanging from a tree in Mametz Wood - photographs taken in August 1916

British artillery fire continued to fall, much of it dropping short onto the Fusiliers.

Evans made what reconnaissance he could and found that the line was not as far north as had been reported and was about 300 yards short of the north-eastern extremity, diagonally to a point just above Wood Support Trench.

He proposed to straighten the line from the north by a surprise attack at 15:30 that afternoon, without a preliminary barrage - but before he could put this plan into operation, the brigade again came under fire from British artillery falling short of the German trenches.

This fire not only pinned down the brigade, but put a stop to any prospect of a surprise attack for the Germans were now thoroughly roused. Progress was made, however, on the western side and the line was brought up to within 300 yards from the northern end of the wood.

Around this time, Wyn Griffith met the brigade signals officer, whom he calls "Taylor". He told him he had met a Chaplain, referred to as "Evans". Evans had been walking the battlefield for days, trying to find his son, who had been reported killed.

Wyn Griffith knew the boy.

Taylor did not speak much Welsh and felt this keenly: "You could not," he said, "talk English to a man who had lost his son."

Evans never did find the boy or his grave.

Man of a working-party attending to a war grave, near Mametz Wood. August 1916

The Padre was later identified by Patricia Evans as the Rev Peter Jones Roberts, a Welsh Methodist minister from Barmouth who had joined up as a chaplain aged 51, beyond the usual age limits.

He had four sons, all of whom were commissioned into the RW Fusiliers. The son second was captured in late 1916; the third badly wounded in 1918. The youngest got into the war in 1918 and survived.

The boy whom Roberts was looking for was his eldest, Glyn, who had been commissioned in 1915 and was serving in the 9th Battalion, which was not in the 38th Division but was close by. He had been killed on 3 July and Roberts had spent a week searching for him.

The splintered remains of a section of Mametz Wood - mature deciduous wood with large trees and very thick undergrowth- photographed in August 1916

But there was much worse to come for Wyn Griffith.

The brigade signals officer had sent relays of runners back during the preparation for the surprise attack, to get the unwanted artillery fire stopped. One of these runners was Wyn Griffith's younger brother, Watcyn, who had enlisted into the 17th RW Fus and then transferred to the Divisional Signal Company.

Watcyn got through with his message, but on the way back he was hit by a shell and killed at once. Wyn Griffith learned of Watcyn's death within an hour - and clearly blamed himself.

As Brigade Major, he had ordered the signals officer to get a message through. "I had sent him to his death," he said, "bearing a message from my own hand, in an endeavour to save other men's brothers."

Watcyn's body was never found and he is one of those whose grave is unknown.

That night, the 38th Division was relieved in the line by the 21st Division and pulled back into rest.

Road signs to the Welsh memorial at Mametz Wood

Robert Graves was with the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Welch Fusiliers in the 33rd Division when they entered Mametz Wood shortly afterwards and he described the scene thus in Good bye to All That:

"Mametz Wood was full of the dead of the Prussian Guards reserve, big men, and the Royal Welch and South Wales Borderers of the new-army battalions, little men.

"There was not a single tree unbroken... There had been bayonet fighting in the wood. There was a man of the South Wales Borderers and one of the Lehr Regiment who had succeeded in bayoneting each other simultaneously.

"A survivor of the fighting told me later that he had seen a young solder of the 14th Royal Welch bayoneting a German in parade-ground style, automatically exclaiming as he had been taught: "in, out, on guard..."

The 38th Division, much reduced by casualties, was moved away into rest.

A total of 190 officers and 3,803 NCOs and men of the 38th Division were killed, wounded or missing.

The red dragon memorial looks on defiantly towards Mametz Wood where around 4,000 men were killed, missing for or injured

Casualties were especially heavy among junior officers and sergeants - leading from the front - but five of the infantry battalions lost their commanding officers.

It was this level of losses, approaching a quarter of the division's strength and probably one-third of the combat units, combined with the severity of the conditions, that made such a mark on the art and literature of the battle, so much of it created by Welsh officers and men.

And made such a mark on the individual and collective memory of the Welsh soldiers, who had endured something which to us is unimaginable.

It was also an experience that created an extraordinary bond between those who had been there - something that could not and cannot be understood by anyone who was not there.

Robert Graves's poem Two Fusiliers, which explicitly refers to Fricourt in one of its verses, and which captures this feeling, provides some fitting last words:

And have we done with war at last?

Well we've been lucky devils, both

And we've no need of bond or oath

to bind our lovely friendship fast.

By firmer stuff

Close bound enough

Show me the two so closely bound

As we, by the wet bond of blood,

By friendship blossoming from mud,

By Death: we faced him, and we found

Beauty in Death,

In dead men, breath.

The casualty rolls are incomplete, but the losses amounted to somewhere between one third and a half of the division's fighting strength.

- Published6 July 2016

- Published14 July 2016

- Published7 July 2016