Mametz Wood and the 38th: The Welsh at the Somme

- Published

The Welsh at Mametz Wood by Christopher Williams, commissioned by David Lloyd George in 1916

On the eve of the 100th anniversary of the battle of Mametz Wood - the first major offensive of World War One for many Welsh soldiers - memorial services are being planned across the country.

The 38th (Welsh) Division paved the way for control of the woodland - nearly a mile wide and more than a mile deep - in northern France. Its capture was of key importance in the Battle of the Somme where Allied forces would fight the Germans on a 15-mile front for five months.

During a bloody five-day battle 3,993 Welsh soldiers were killed, missing or injured, putting their division out of action for almost a year.

In the first of two written documentaries, Lieutenant-General Jonathon Riley, late of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, describes the events leading up to and during the battle, recorded in such depth thanks to the literary tradition of his former regiment.

Lieutenant General Riley is a former Commander British Forces Iraq and Deputy Commander NATO forces in Afghanistan; now Visiting Professor in War Studies at King's College London and Chairman of the Royal Welch Fusiliers Regimental Trust. Editor of Llewelyn Wyn Griffith's memoir Up to Mametz - and Beyond and author of 17 other books.

Between 2001 and 2015, the British Armed Forces lost 454 men and women in Afghanistan.

We lost that number on one morning, 7 July 1916, before the attack by the 38th (Welsh) Division had even reached the edge of its objective, Mametz Wood on the Somme battlefield.

The 38th Division had been raised in late 1914 as part of Kitchener's New Army - an army for the long war that he was the first to recognise.

Formations like it were being raised all over the country but Wales more than played its part in fielding the huge new army.

In spite of the paucity of population in Wales, The Royal Welch Fusiliers, for example, raised the fourth highest number of battalions - a total of 45 - of all regiments on the Army List during the war, beaten only by those with large urban populations: Greater London and Middlesex, Durham and Manchester.

David Lloyd George was active in the campaign to expand the army in Wales, espousing even a Welsh Army Corps.

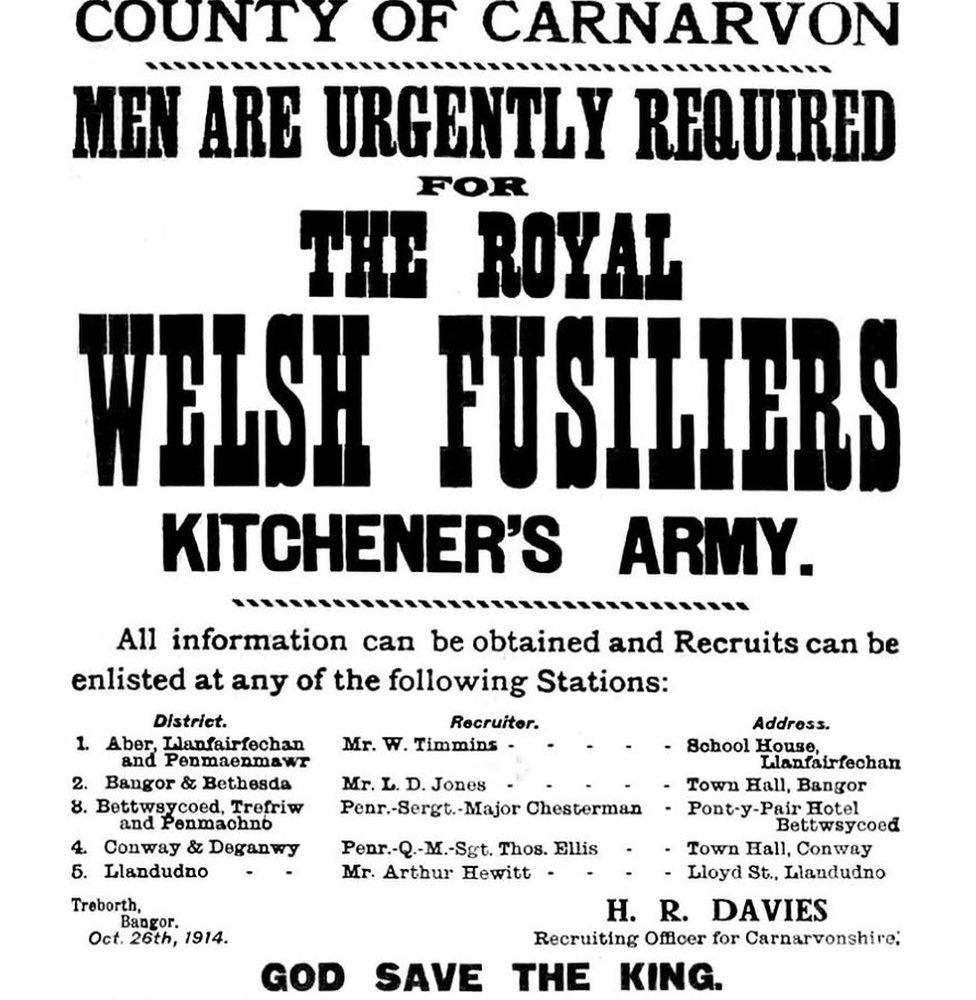

A recruitment poster published in 1914 for 'Kitchener's Army' named after Horatio Kitchener, the then secretary of state for war

This particular initiative came to nothing.

In part, even allowing for the herculean effort of raising the numbers of troops that it did, Wales could not support a corps of perhaps 40,000 men for several years - especially as the high command of the army would not extract the regular Welsh infantry and cavalry units from their parent formations to provide the backbone of a new corps.

Politically, too, a Welsh Army Corps would have opened the door for similar formations in Scotland and Ireland.

Mametz

An army corps is a powerful instrument in the formation of new nations, as those of Australia, New Zealand and Canada showed and at this time, just before the war, the great political issue of the moment had been Irish home rule.

This had been shelved for the duration, by mutual consent, and no one in London would support any move that would bring it back to prominence while the bigger matter of war with Germany demanded their full attention.

The division's first eight months were spent in training in north Wales, at Winchester and on Salisbury Plain.

Much of this seems to have been very basic stuff: close order drill, route marches and PT to get the men fit, equipment husbandry, weapon training, minor tactics and courses for specialists like signallers, medics, Lewis and Vickers gunners.

Artists and writers who served at Mametz Wood, l-r clockwise: Siegfried Sassoon (Getty); Frank Richards (RWF Museum); Sir Wynn Powell Wheldon (National Portrait Gallery, London; David Jones; Robert Graves (PA)

One reason we know so much about the Battle of Mametz lies in the literary tradition of The Royal Welch Fusiliers.

Serving at Mametz, at various times, were Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, James Dunn, Frank Richards, Llewellyn Wyn Griffith, David Jones, Bill Tucker, Harold Gladstone Lewis, and Wynn Powell Wheldon.

These are significant figures in the artistic landscape of the Great War.

The fighting strength of the 38th Welsh Division which, including its combat support and administrative units, stood at about 18,500 men, lay chiefly in its three infantry brigades: 113, 114 and 115 Brigades.

Each of these were composed of four or five battalions drawn from the Welsh Regiments: The Royal Welch Fusiliers, which recruited all over Wales as well as in London and Birmingham; the South Wales Borders, which recruited in south-east Wales and the English border county of Monmouthshire; and the Welch Regiment, drawn from south and west Wales.

However, there was scarcely anyone with military experience in these battalions, save for the few regular officers and NCOs drafted in to form and train them.

Officers in the Service divisions, like 38th, were selected therefore not on any basis of military efficiency but on the basis of patronage - often in the gift of Lloyd George himself.

Distinguished Welsh writer and broadcaster Llewelyn Wyn Griffith (right) described Brigadier-General Llewellyn Alberic Emilius Price-Davies (left) as the second most stupid soldier he ever met

In the 15th (London Welsh) Battalion of The Royal Welch Fusiliers, Noel Evans, for example, came from a noted Merionethshire family.

He was later deputy director of public prosecutions, a JP, high sheriff and deputy lord lieutenant of the county; Goronwy Owen was related to Lloyd George by marriage.

He had a very good war, ending as a Lieutenant-Colonel with a DSO and was later Liberal MP for Caernarvonshire and president of British Controlled Oilfields.

Llewelyn Wyn Griffith owed his commission at least in part to the patronage of the Liberal MP Ellis Griffith.

After its months of basic training, the 38th Division was in late November 1915 reviewed by Queen Mary.

One of its brigades, 113 (Royal Welch) Brigade, also received a new commander, Brigadier-General Llewellyn Alberic Emilius Price-Davies, who replaced Brigadier-General Owen Thomas - a man who had done more than anyone else to to invigorate recruiting in Wales - in controversial circumstances; although later knighted, Owen Thomas lost all three of his sons killed during the war.

Llewelyn Wyn Griffith described Price-Davies as the second most stupid soldier he ever met.

Price-Davies had done well in the small wars which preceded 1914 and had won a VC and a DSO in South Africa. He was, said Wyn Griffith, too dull to be frightened.

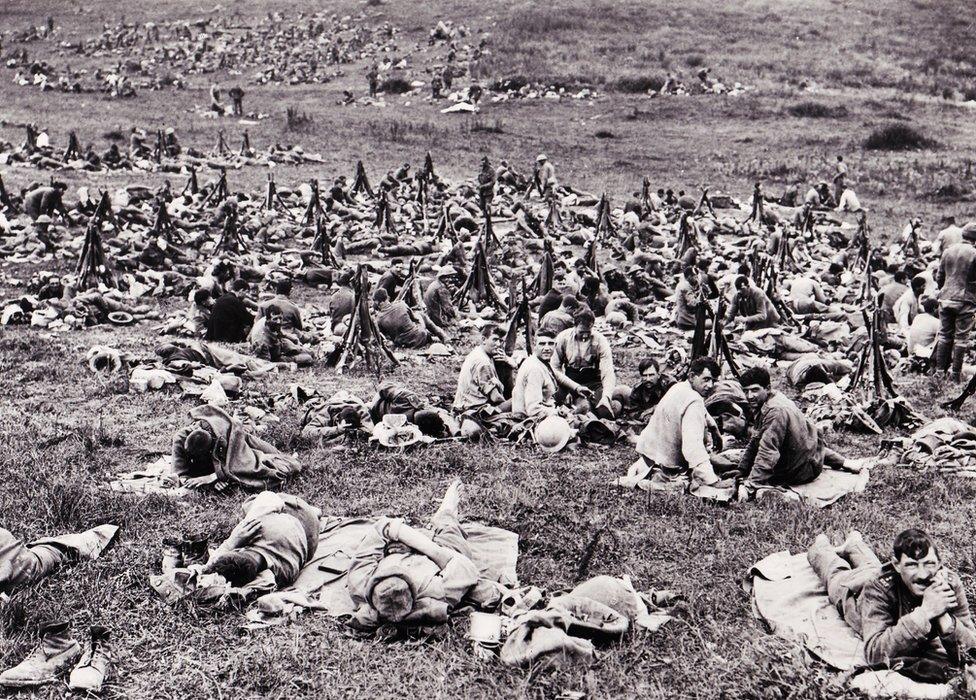

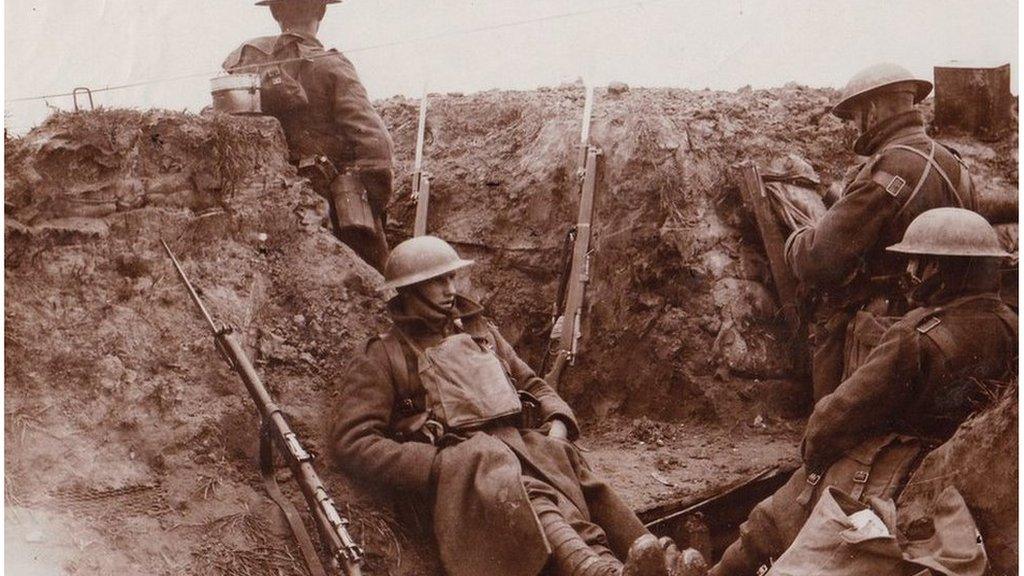

Soldiers of the Royal Welch Fusiliers resting after the attack on 1 July, a week before the assault of Mametz Wood begins

His recently published letters fail to give us a kinder view of him.

Known as 'Jane' by his fellow regulars, he exemplified the thoughtless brutality that is many people's stereotype of the Great War general officer - unimaginative, slow, fascinated by the minor trivia of latrine buckets and polished brass.

He was one of those who had to be promoted to fill command appointments in a rapidly expanding army, promoted on the basis that bravery in combat signifies the ability to exercise high command - but for whom the demands of modern war were all too much.

Under Price-Davies, the brigade embarked for service in France on 1 December 1915 in pouring rain.

Not long after its arrival, the division was doing duty in trenches at Laventie, where some of its units took part in the little-known second Christmas Truce - that again is another story.

From January until June 1916 the battalions and brigades took their turn at the drudgery of trenches, learning their trade and being slowly transformed from a bunch of amateurs into something approaching units capable of simple tasks.

The Battle of the Somme

Began on 1 July 1916 and was fought along a 15-mile front near the River Somme in northern France

19,240 British soldiers died on the first day - the bloodiest day in the history of the British army

The British captured just three square miles of territory on the first day

At the end of hostilities, five months later, the British had advanced just seven miles and failed to break the German defence

In total, there were more than a million dead and wounded on all sides, including 420,000 British, about 200,000 from France and an estimated 465,000 from Germany

Find out more:

These tours of trenches were not, as many people think, affairs lasting months.

In the desperate days of late 1914 and early 1915 there were recorded instances of units holding the line for weeks at a time but by the spring of 1915, most divisions operated a rotation in which each brigade spent a few days in the front line; then a few days in the support line, then days in reserve - these were often the worst period as the men would spend all night on duties like carrying supplies up to the line, or sand-bagging and wiring and other heavy work.

This would be followed by a rest period and training, before the rotation began again.

In spite of all this, the 38th Division could not be described as capable of taking part in a major combined-arms operation against fortified German positions in mid 1916 - which was the task they would be given at Mametz.

And so we come to the summer of 1916.

Allied war strategy for the year had been formulated during a major conference at Chantilly in December 1915, where it was agreed that major, simultaneous offensives would be launched by the Russians, the Italians in the Alps, and the British and French in the West - thus assailing the Central Powers around the whole perimeter of the war.

Shortly after the conference, General Sir Douglas Haig replaced Sir John French as Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force.

Haig favoured an attack in Flanders, which was easily served by the line of communication through the Channel Ports and which, if it went well, might even drive the Germans away from the Belgian coast from where their submarines were decimating British shipping.

However, rather as we were with the Americans in Iraq and Afghanistan, the British in 1916 were the junior partners in a coalition with the French and in February 1916, General Joseph Joffre, the French C-in-C, insisted on a joint British and French attack astride the River Somme in Picardy, beginning in August.

Shortly afterwards, the Germans launched their attack around Verdun.

The French threw all they had into preventing a German breakthrough here, which if it succeeded would open a major avenue of advance towards Paris.

Moving up for the Mametz attack: A lone Welsh soldier in the trenches in July 1916

Their commitment to the Somme battle was thus significantly reduced and the bulk of the burden shifted to the British and Imperial troops. Twenty divisions were now committed as against only 13 French divisions.

Moreover as the mincing machine of Verdun developed, the aim of the Somme offensive changed from being part of a decisive allied blow against Germany, to one of relieving the pressure on the French; the date of the attack was brought forward from August to July.

Among senior British commanders there was disagreement on how the required effect would be achieved.

'Bite-and-hold'

General Sir Henry Rawlinson, whose Fourth Army would conduct the attack, favoured a 'bite-and-hold' approach, which would concentrate resources and which recognised the British inability to exploit a breakthrough even if one were made.

Haig's concept, by contrast, was for a more general attack on a wider front.

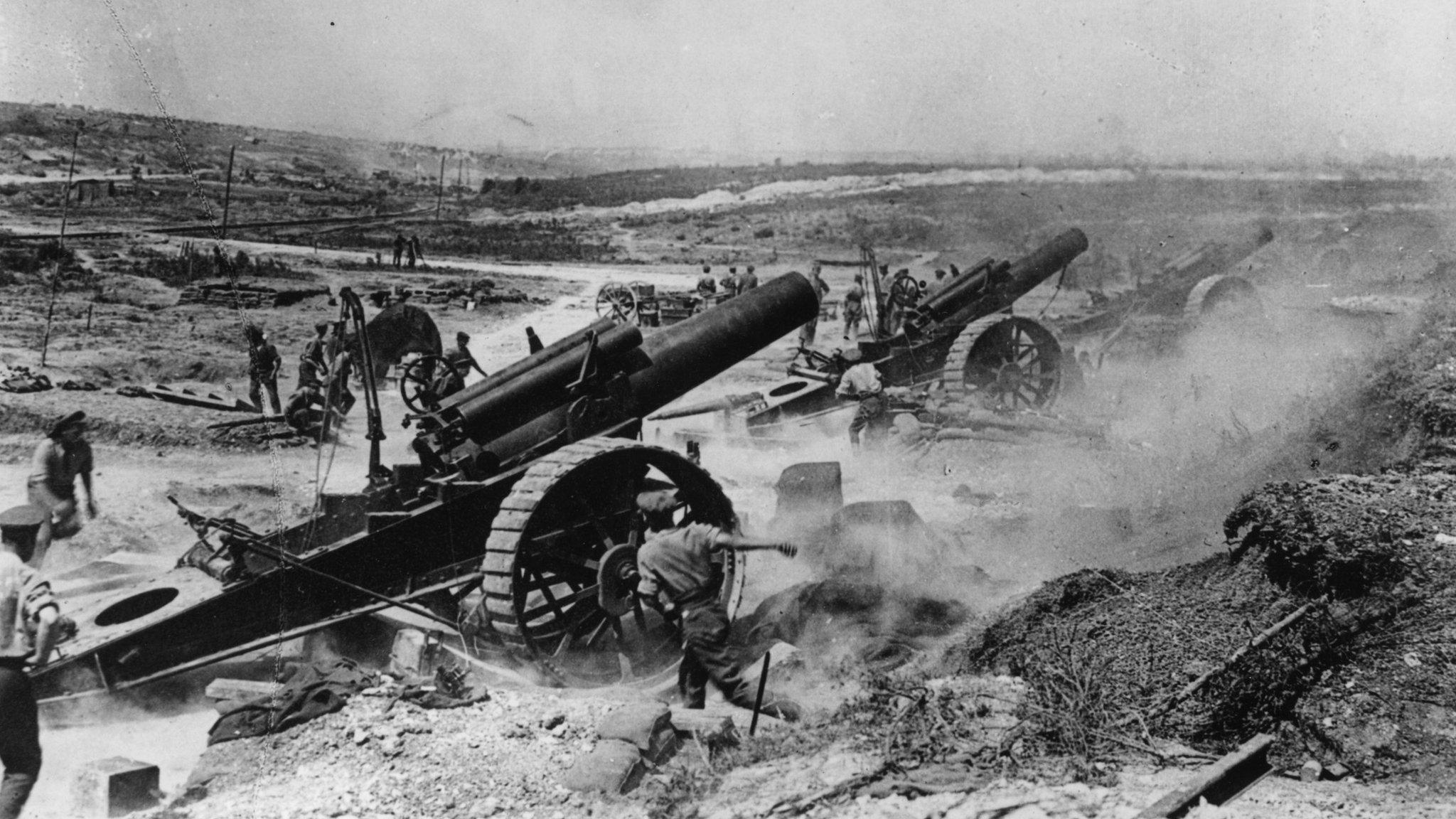

Much emphasis was based on the ability of allied artillery to destroy German wire and fortifications and allow the infantry first to break in to the German defences, and then break through.

In reality, British field artillery was still woefully behind that of the Germans.

These are the air photographs taken of Mametz for planning purposes immediately before the Somme offensive, in late June 1916 (RWF Museum)

Most of it was of light or medium calibres - without therefore the weight of shell needed to cut up barbed wire or demolish deep dugouts - nor had the huge strides in fuse technology that appeared in late 1917 yet emerged, which would allow artillery to do these things with devastating effect.

Finally, without battlefield radio, artillery was still controlled on pre-arranged timings.

This meant that the infantry had to keep up with the artillery fire as it shifted, rather than the artillery being manoeuvred to support the infantry.

If the infantry was held up, the barrage would move on, leaving them exposed.

Air support too was in its infancy and could do little other than deliver machine gun fire or small bombs, or direct artillery by observing the fall of shot and sending correction messages.

Rawlinson was, too, well aware of the quality of the infantry with which he had to make this assault.

After the losses among the regular and reserve forces during 1914 and 1915, the bulk of the British Expeditionary Force was made up of the volunteers who had joined Kitchener's New Army.

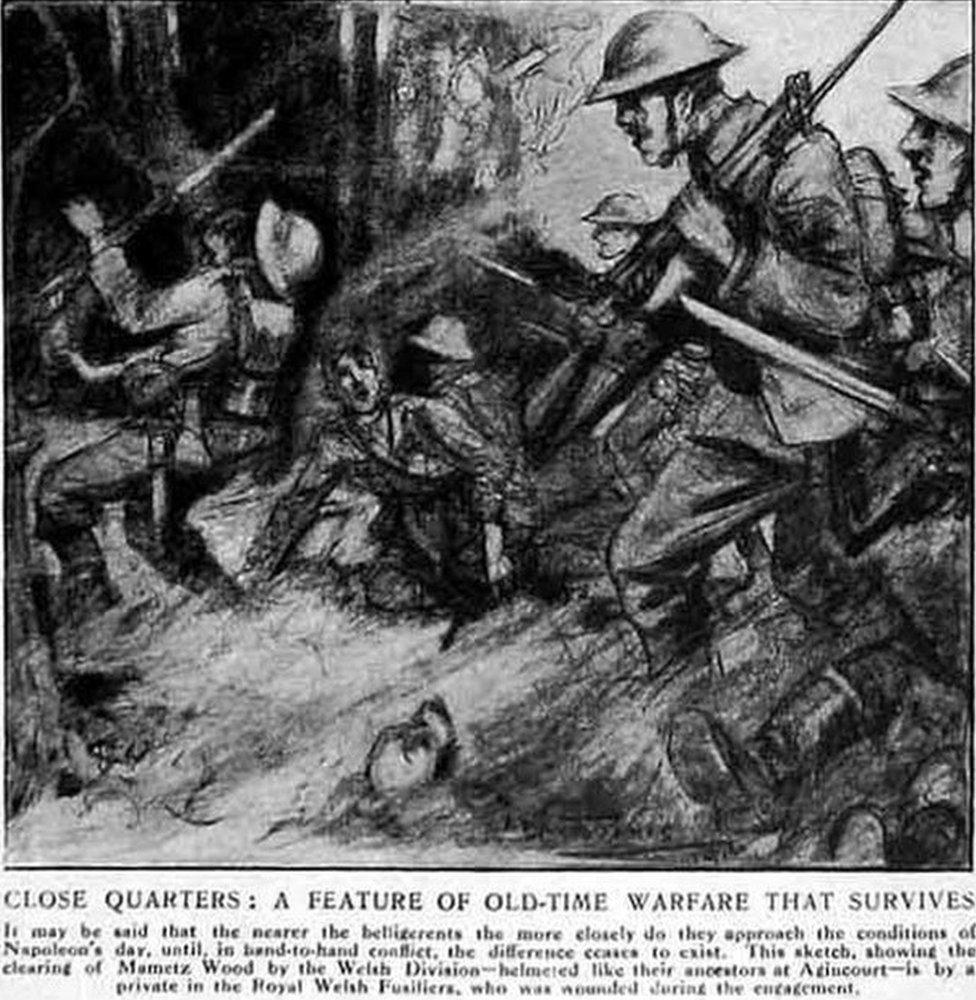

Assault on Mametz Wood by poet and artist David Jones who took part in the battle

Kitchener had formed this army with the intention of having it ready for major operations in 1917: yet now, strategic considerations over-ruled their lack of expertise and these units and formations were to be required to undertake a difficult operation, without enough experience, a year earlier than had been intended, and without the compensation of effective fire support.

This is not to say that preparations were not extensive and as thorough as they could be in a relatively short time.

In fact they were the most extensive that had yet been undertaken in the entire history of the British Army in war.

Millions of shells and tons of other stores of all kinds - food, water, medical equipment, barbed wire, small arms ammunition, spare clothing and weapons - were accumulated behind the front, all very difficult to conceal from German air reconnaissance. Many miles of standard and narrow gauge railway and tramway were laid.

All roads were improved and new causeways laid over marshy ground.

Water for men and horses

Additional dugouts to shelter troops were built by the Labour Corps; magazines and dumps were built, dressing stations and field hospitals erected and staffed.

Gun emplacements and miles of communication trenches were dug.

Telephone cables were laid and mining operations undertaken beneath the German lines.

In most places, water for men and horses was a serious problem so that many wells and boreholes had to be sunk, and more than 100 pumping stations built.

All this is sometimes overlooked in the general recriminations about the level of casualties during the battle.

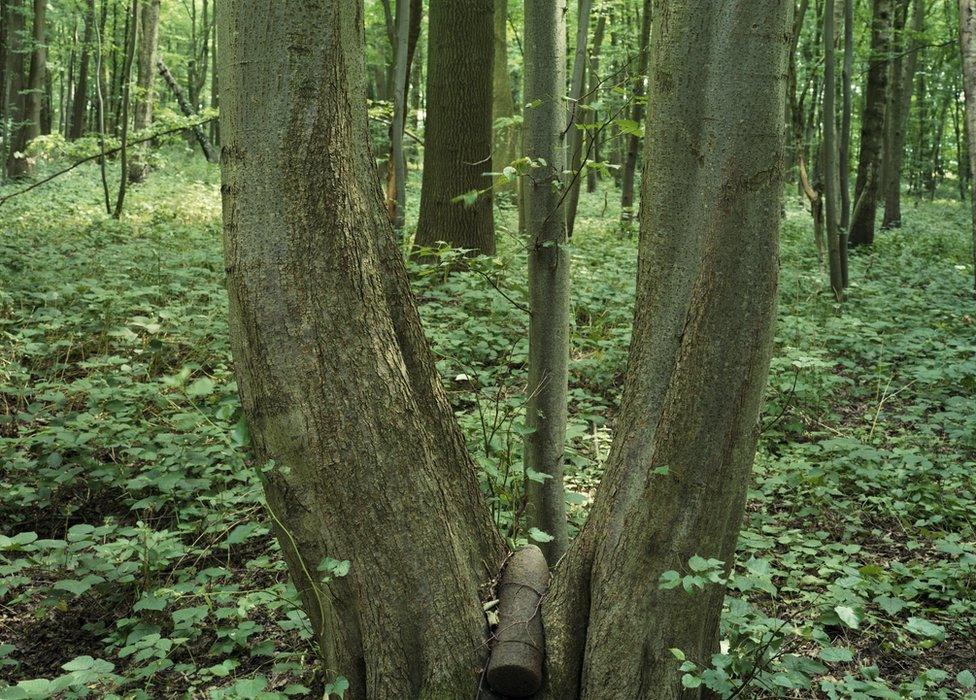

Photographer Aled Rhys Hughes has been visiting Mametz Wood over the last five years

With the benefit of hindsight it is not surprising that except for the area around Montaubin, the objectives of 1 July 1916 were not gained.

Why not surprising then, in spite of all the preparations?

First, because - as we mentioned earlier - the majority of the artillery used in the bombardment that preceded the battle was of light calibres - 15 and 18-pounders and trench mortars.

Although there were 1,500 guns firing in support of the attack, and they fired 1.6 million rounds, only one-third of those were medium or heavy calibres.

The weight of shell was not enough to break up deep German dugouts, nor the extensive belts of German barbed wire - in many places, between 100 and 200 metres thick.

Nor were the fuses then in use sensitive enough to be detonated by a slight brush with the wire.

In many places, assaulting troops came up against unbroken wire covered by German machine-gun fire, which stopped them; and then artillery fire that killed them.

The German artillery, not the machine gun, was the big killer on the post-1915 battlefields of the Great War.

An exhibition at the National Library for Wales of Aled Rhys Hughes' book, Mametz, shows discarded artillery shells

Secondly, because as so often until 1918, there were some places where penetrations were made.

All too often, in such cases, the assaulting troops broke in, but could not break through because of the way that the Germans organised their defence in depth, had massive artillery support on call, and always, always, counter-attacked immediately.

Some witnesses recalled the German signal rockets going up for fire on their defensive tasks, looking "like a line of poplar trees".

But there was some success around Montauban.

The 7th and 21st Divisions broke into the German lines at Fricourt and captured Mametz village.

Taking part in that attack was the 1st Battalion R.W. Fusiliers, Siegfried Sassoon among them, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel C.I. Stockwell, ('Buffalo Bill') a participant in the famous Christmas Truce of 1914.

At 06.45 in the morning, the bombardment rose to a crescendo. At 07.25, mines were fired under the German lines.

At first, the German resistance was strong and the assaults by two other battalions were stopped and a second attack in the afternoon, not properly co-ordinated, was also stopped with the loss of half the attacking troops.

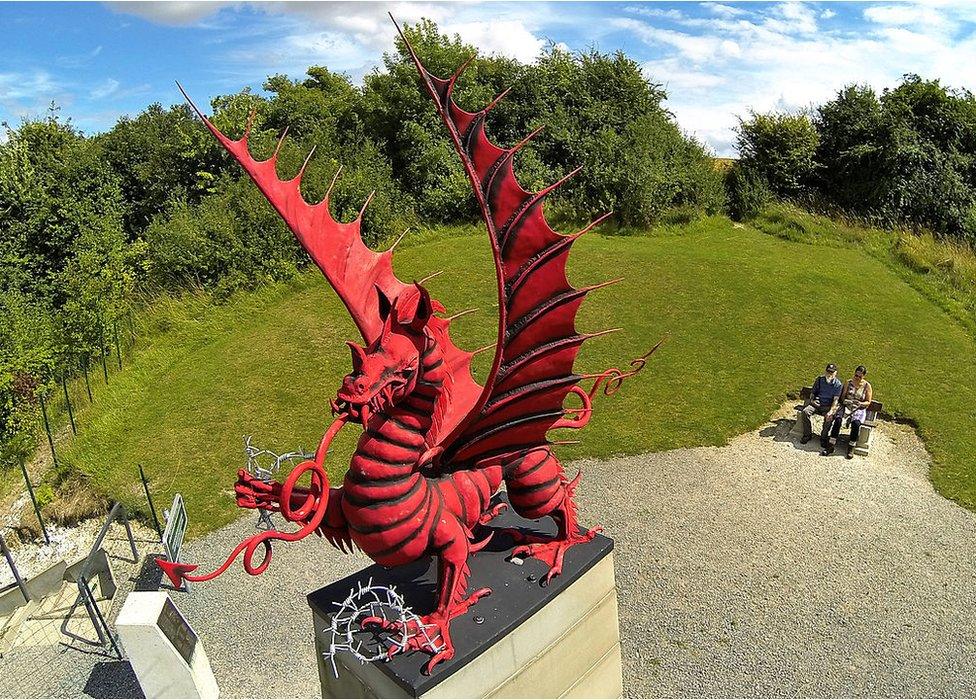

The memorial by Welsh sculptor David Petersen was erected in 1987 - a Welsh red dragon on a three-metre stone plinth facing the wood and tearing at barbed wire

At 16.00, 1st Royal Welch Fusiliers was ordered to capture the high ground to the east of Fricourt. 1 R.W. Fus, and indeed the rest of 20 Infantry Brigade to which it belonged, had been specially organised and trained by Stockwell and their brigade commander, another R.W. Fusilier, John Minshull-Ford (known as 'Scatter').

Using techniques later adopted by the whole army, the battalion infiltrated using shell-holes and portions of captured German trenches, leading with bombing parties supported by other parties carrying ammunition - giving rise to the expression "bombing along".

By dark - about 22.30, Sunken Road trench had been consolidated and several hundred prisoners taken, for the loss of only four men killed and 35 wounded: not at all the usual story of 1 July 1916.

That evening, Haig decided to reinforce what success he had, and attack again around Fricourt in order to capture the German second defence line at its closest point between Longeval and Bazentin.

Rawlinson had little option but to assault this position, which was a low but commanding ridge, frontally.

He decided to do so between the two large woods of Mametz on the left and Trones on the right.

The assault would be phased in order to provide the maximum possible weight of artillery fire in support of the assaulting troops.

Mametz would be taken first, to secure the flank against the inevitable German counter-attack.

- Published7 July 2016

- Published14 July 2016

- Published7 July 2016

- Published4 July 2016

- Published4 July 2016