Plaid Cymru's first MP 'helped change course of a nation'

- Published

Gwynfor Evans was elected Plaid Cymru's first MP after a by-election held in Carmarthen on 14 July 1966. Dr Martin Johnes, a lecturer at Swansea University argues it was an election which "helped change the course of a nation".

In 1964, Emrys Roberts, Plaid Cymru's general secretary, argued his party was scarcely known and seen as fanatical, old fashioned, puritan and almost synonymous with the Welsh language.

This was rooted in the affectionate but ultimately retrograde view the majority of Welsh people then had of traditional Welsh culture.

Welsh identity was something to be celebrated in sport or on St David's Day, but it was also associated with a chapel and linguistic culture perceived to be out of kilter with modern life.

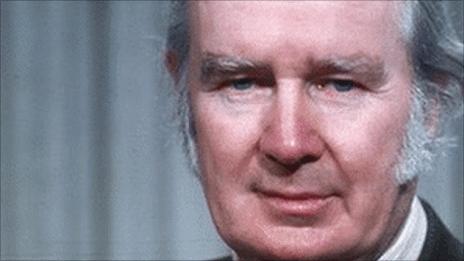

However, some in Plaid Cymru also blamed its leader, Gwynfor Evans, for the party's marginal position in Welsh politics.

Roberts accused him of being "shy, weak, unimaginative, lacking in drive".

The 1966 general election seemed to confirm the analysis. Plaid Cymru won just 4.3% of the Welsh vote.

Lady Megan Lloyd George was elected Carmarthen's MP in a 1957 by-election. She held the seat until her death from cancer on 14 May 1966

Shortly after that election, Megan Lloyd George, Carmarthen's Labour MP, died.

This meant a by-election in Gwynfor Evans's home constituency at a time when the Labour government was enduring criticism of its financial policies and suffering internal strife.

Within the constituency, there were significant concerns that local collieries and rural schools were threatened with closure, while farmers worried about small business taxes.

The Labour candidate was a shy north Walian who was perceived to be condescending, none of which endeared him to the local party and its supporters.

Plaid Cymru, in contrast, fought an effective and nuanced campaign, using different slogans in the rural west of the constituency ('For a better Wales') and the industrial east ('For work in Wales').

Here's how the Carmarthen by-election result was announced

Despite the favourable circumstances, few anticipated a Plaid Cymru victory, let alone the comfortable 2,436 majority Mr Evans secured.

Outside the count, a jubilant crowd of 2,000 sang the national anthem and waved Welsh flags.

The local newspaper's headline declared: "Election of the Century - Plaid's Astonishing Win."

Evans's nationalism was rooted in a deep personal patriotism but also a belief in the value of democracy and small communities.

This, together with his personal dignity and lack of pretention, made him a genuinely popular figure with the local electorate and young nationalists, even if some of his colleagues did see him as politically naive.

Gwynfor Evans, greeted by crowds of press and supporters at the St Stephen's entrance of the Palace of Westminster on July 21st 1966

When Mr Evans took his seat in the Commons, there was an excited crowd there to welcome him.

The Daily Mirror described it as "one of those highly-emotional occasions the Welsh do so well. All leeks and flags, hymns and chants as they invaded the capital by rail and coach."

A porter at the house remarked: "There's been nothing like it since the Beatles were here."

Welsh nationalism had suddenly and unexpectedly come of age and Mr Evans was its icon.

It was not just Welsh nationalists who were delighted. There was a positive reaction to the win and to Mr Evans himself in much of England, not least among the right-leaning press who saw it as a welcome blow to the government and a departure from old party politics.

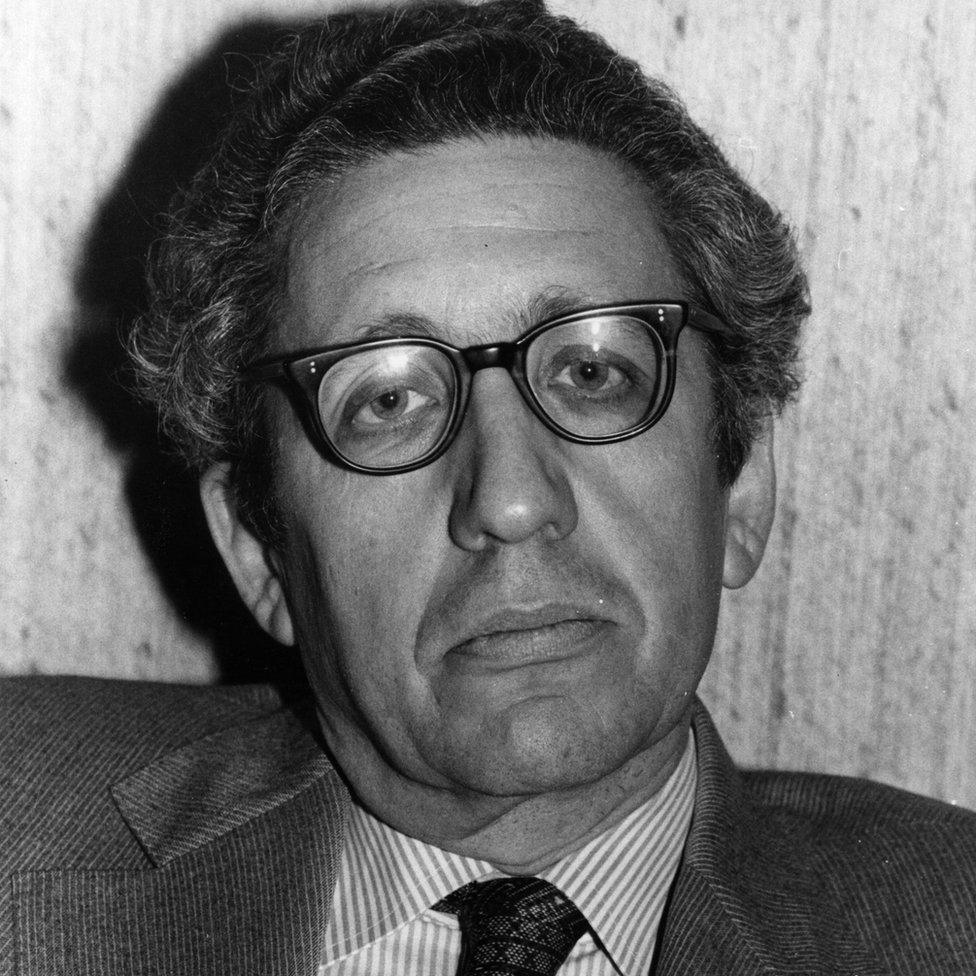

During the 1970s, Bernard Levin wrote a political column for the Spectator, and also wrote for the Daily Mail and the Daily Express

In 1970, Bernard Levin, one of the most famous journalists of the time, looked back on the by-election as part of a trend of ordinary voters resisting the might of central government.

The nationalist feeling was, he argued, "mere top-dressing, which provided the character and flavour of the movement without necessarily expressing the fundamental truth in what was affecting its supporters".

For Levin, Mr Evans's victory was evidence that ordinary people felt disconnected and lost.

They voted Plaid Cymru to take back control.

That interpretation underestimated the emotional pull of patriotism, but it does point to how the alienation and anger with mainstream politics that contributed so much to the 2016 EU referendum result long predate the governments of Tony Blair that are usually blamed for falling faith in the political system.

Welsh hostility

Many reactions in Wales were less sympathetic than those of the English right.

As politicians and commentators worried about how Wales would replace the jobs being shed in a declining coal industry, nationalism was widely seen as a distraction rather than a solution.

In the wake of Mr Evans's victory, a Caernarfon newspaper argued economic problems showed "vividly the irrelevance of what he represents. The peoples of Britain - all of us - stand or fall together".

Such hostility to nationalism did extend beyond practical concerns. World War Two was little more than 20 years past and was blamed by many on the forces of nationalism.

Some Labour MPs reputedly refused to speak to Mr Evans or even look at him in the House of Commons.

Of course, this also owed something to Labour fears the Carmarthen result had opened the electoral door for Plaid Cymru at a time when economic pessimism in industrial communities meant they were susceptible to new alternatives.

Plaid Cymru slashed huge Labour majorities at by-elections in Rhondda West (1967) and Caerphilly (1968).

Although both seats remained in Labour hands and the results owed much to protest votes, Plaid Cymru had quite suddenly been transformed into a serious political force and it was now evident that popular patriotism had moved beyond the realms of language, chapel and sport.

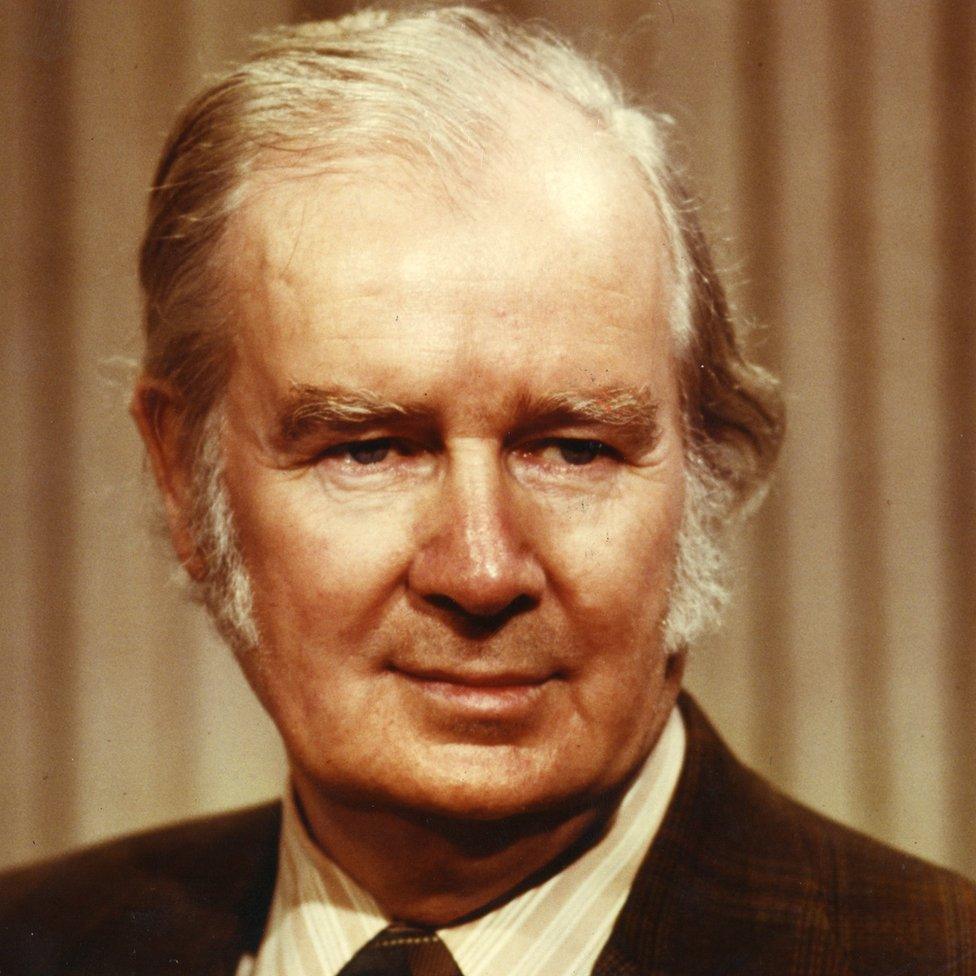

Cledwyn Hughes, later Lord Cledwyn of Penrhos, was the MP for Anglesey for 28 years

In this new climate, concessions were made to Welsh identity.

In 1967, the first Welsh Language Act was passed, giving the two languages of Wales equal validity.

Cledwyn Hughes, secretary of state for Wales from 1966 to 1968, even tried to create an elected Welsh assembly as part of a reform of local government.

That was a step too far for many in Labour and there were fears in cabinet it would encourage nationalism in both Wales and Scotland.

Mr Hughes was thus replaced by George Thomas, who was secretary of state from 1968 to 1970 and seemed to have a virulent and paranoid hatred of nationalism and the Welsh language.

George Thomas, later Viscount Tonypandy, was a Labour MP in Cardiff from 1945 to 1983. He was Speaker of the House of Commons between 1976 and 1983

Figures like Mr Thomas had previously largely ignored Plaid Cymru. Now they devoted energy to attacking and hampering the nationalists.

For those who worried that Carmarthen 1966 was the beginning of a nationalist revolution in Welsh politics, the 1970 general election provided some reassurance.

Plaid Cymru contested every Welsh seat for the first time, but 25 of its 36 candidates lost their deposits, while Mr Evans was defeated by nearly 4,000 votes.

Overall, Plaid won more than 20% of votes in just seven constituencies and it only secured 11.5% of the vote in Wales as a whole.

Despite this step backwards, the Carmarthen by-election had shown Plaid Cymru was more than a language pressure group.

The party had proved itself to be electable and put serious discussion of whether Wales could be self-governing in any way on the agenda.

Labour could no longer be complacent and Welsh politics would never be the same again.

The by-election also fed into a new sense of confidence emerging among young Welsh people.

It was part of the 1960s' atmosphere of optimism and rebellion; it proved change was possible; it proved that Welshness was more than chapels and rugby.

Dafydd Iwan after his release from Cardiff prison on 6 February 1970. He was jailed for daubing English road signs as part of a Welsh Language Society campaign

By 1969 a Welsh magazine could declare: "Wales herself is today at the start of a renaissance... Slowly, but inevitably, the old barriers of resentment, insecurity and isolation are being broken. Self-assurance and national confidence is emerging at an entirely new level."

That was not just evident in the protests of Welsh language society Cymdeithas yr Iaith and the songs of Dafydd Iwan, but also by the 1970s in the behaviour of sports crowds and the growing appetite for Welsh-medium education and Welsh history.

Mr Evans's victory of course was not the only cause, but it was more than just a symbol of a cultural and political shift in Wales.

It was an election that helped change the course of a nation.

- Published1 September 2012