Forgotten legacy of the actor and missionary Gareth Hughes

- Published

Who was the first Welsh film star? A few might say Anthony Hopkins. Some might say Stanley Baker. The Oscar-winning Ray Milland might come to mind or even Ivor Novello.

None of these were the first Welsh star, though. That title goes to a man who is all but forgotten in his homeland.

A man who dancer Isadora Duncan once called "the world's greatest dancer", a man filmmaker Cecil B De Mille called "the young idealist".

A man whose performance was once described by legendary producer David Belasco as "among the most magnificent that I have ever seen on the English-speaking stage".

This forgotten star from Llanelli was once one of the most lauded actors in America. This is his story.

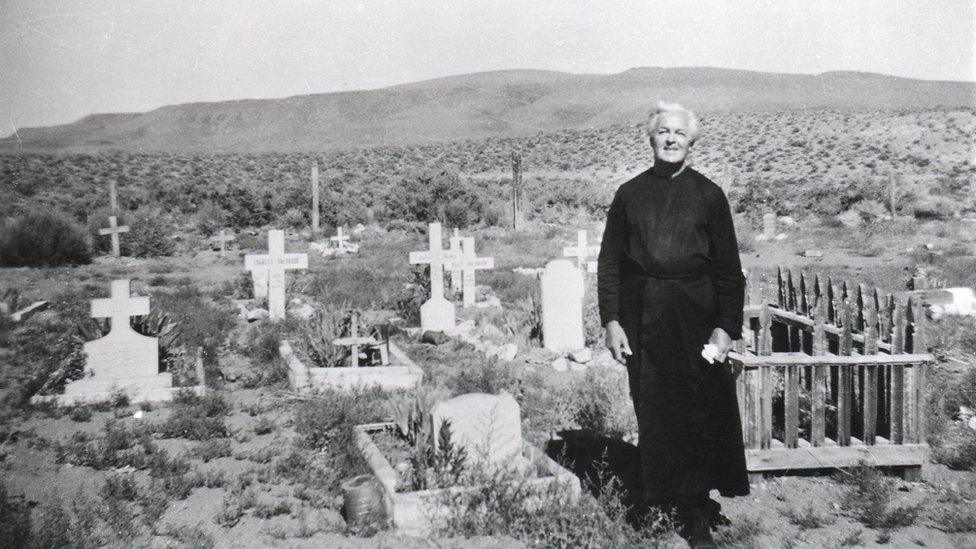

On a cold, February morning in 1992, a small group gathered at the old Mission House on the Pyramid Lake Indian Reservation at Nixon, Nevada.

The whitewashed and wooden slatted St John Baptist's House had been the home of the protestant mission to the Paiute Indians in the 1940s, 50s and 60s.

Now uninhabitable and due to be torn down, it had become the scene of one last moment of mystery and excitement as a trunk belonging to former resident, Welsh missionary Brother David, was brought from the cellar where it had been discovered, overlooked for many years, to be officially opened.

Present were Lorraine Wadsworth, a Paiute; Carrie Townley-Porter, historian and archivist to the protestant diocese of Nevada; and a handful of other interested local people: all gathered to witness the opening of the dirty and rusted, old trunk which bore the legend "G. H." for Gareth Hughes, Brother David's former name.

A stranger would have been baffled as to why the discarded belongings of an old missionary would be of any interest to anyone at all.

But, to those who knew even a little of the history of Brother David, the event would have provoked a wide range of emotions.

The trunk was brought into the daylight, carefully opened and, as the smell of rotting clothing wafted away, a disappointment spread through the gathering.

Not a shred of his Celtic origins, his salad days notoriety as a household name, his service at Nixon.

The anticipation and brief spark of excitement snuffed out, the trail to the Welshman who had impacted so greatly on their lives gone, as quickly as the stale air in the trunk.

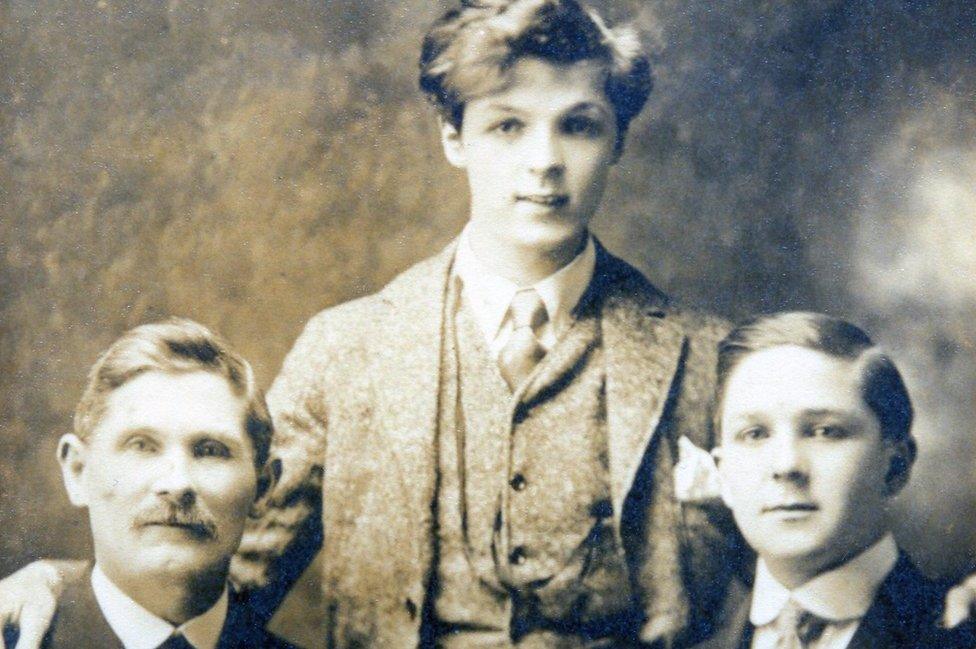

Gareth Hughes is pictured with his father and brother

The key to their disappointment lies in the extraordinary story of a man who had crammed several lives into just one - the story of a boy from a Welsh tin town who had known stardom and poverty, acclaim and hatred but then had aspired to a far greater reward.

His was a trail which, to all but a few, had gone cold in the passing of time.

William John Hughes, as he was born in Dafen, Llanelli in 1894, was the son of a tinplate worker whose oratory skills won him many a cup and silver purse in his day.

William John, himself, had performance in his blood and, with his family's blessing, chose to pursue an acting career. London beckoned and he accepted the invitation.

US success

Adopting the name Gareth Hughes several engagements with companies touring Shakespeare and Melodrama followed and then, with a company of Welsh Players, he sailed for New York in 1914 to take a slice of Wales to the Broadway stage.

Undaunted by the less than hoped-for response to their play, Hughes saw unimagined opportunities in America and chose to stay. He rapidly found work, again and again, moving in ever-important theatrical circles.

In 1915, in an astoundingly brief appearance, his portrayal of a dying soldier stole the cream of Broadway reviews for that season.

In 1917 he was billed as "America's Foremost Young Actor" and he had made history in the USA by playing two stage roles never before played by a man - Everyman and Ariel.

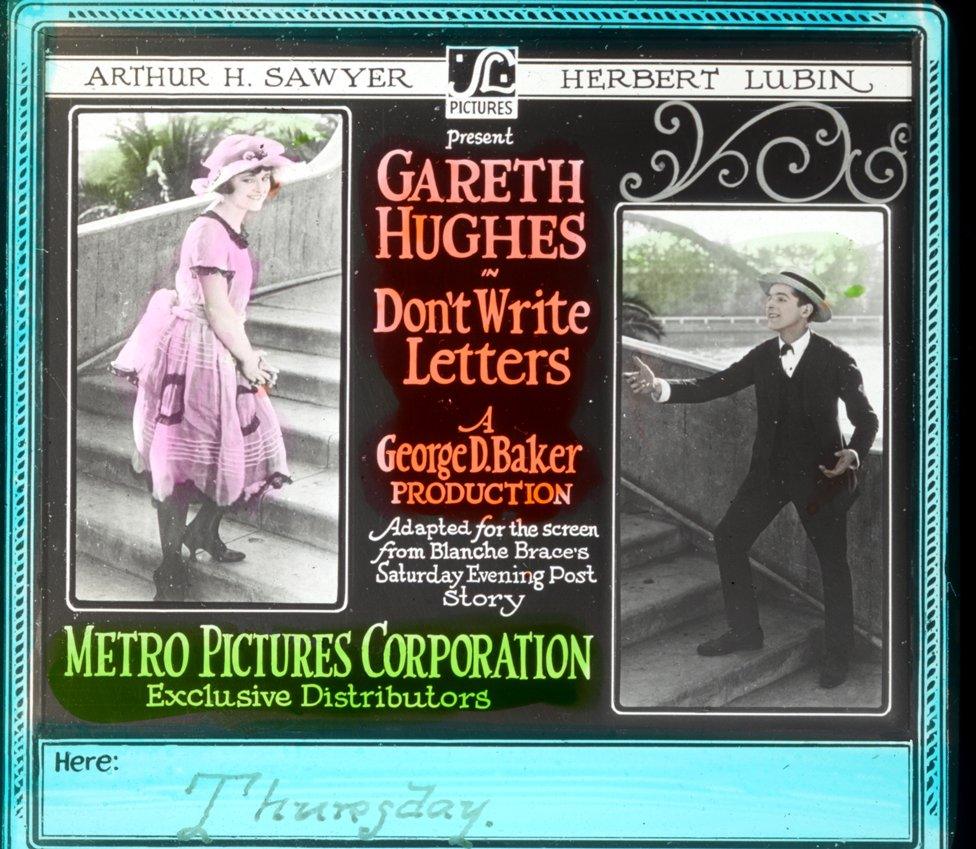

Broadway success opened the door to the silver screen for Hughes, who made his fist movie in Chicago in 1915.

More starring roles on Broadway followed and then with a respectfully, growing portfolio of films under his belt, he was invited to Hollywood.

In 1920 he was offered a contract by Metro Pictures and billed as their "boy star".

No sooner was the ink of his signature dry on the contract than J. M. Barrie, author of Peter Pan, chose Hughes to play the lead in the film of his book Sentimental Tommy.

Loaned by Metro to Famous Players Lasky, Hughes ignored his worsening appendicitis to spend two months back on the east coast fulfilling this wonderful opportunity: the only film of forty-six which he deemed worthy in his career.

A town house in Hollywood and a lodge in Laurel Canyon, two cars, a chauffeur, horses and a groom were the adopted lifestyle while he mingled with the great actors of the day.

With Charlie Chaplin he attended the funeral of actor Rudolph Valentino, who had played a small part in Hughes' first Hollywood film. He attended opening nights with the likes of screen Diva Theda Bara.

Clara Bow, then unknown, danced on a table next to Hughes in one film, while Bela Lugosi played his mean father in another.

Hughes moved in a galaxy of stars and was truly a star himself. He engaged in Vaudeville, as many stars did.

Fading star

But stars fade - and Hughes' began to wane. His youthful demeanour belied his advancing years.

There was little demand for a thirty something-year-old Peter Pan, a role he had once coveted and declaimed, "Why must it always be a Peterless Pan" when Barrie chose an actress for the part.

His film career was settling gently towards more of a B movie existence when, in 1929, the Wall Street crash ruined him, as it destroyed so many others.

His only "talkies" were not great successes and, in the first years of the depression, Hughes disappeared from view.

He moved from one small apartment to another in the Echo Park area of Los Angeles, poor and without work, until Franklin D Roosevelt came to the rescue.

The Federal Theatre Project, Roosevelt's remedy for this particular ailing profession brought Gareth back to the stage.

He began as an actor on $94 (£71) a month - a far cry from his weekly take as a star. He was then appointed as director of Shakespearean and religious drama for the project in Los Angeles on $175.76 (£134.15) a month.

He worked hard and loved his work, but at the cost of his health. He once again starred as Shylock in 1937, a part he had played at school in 1909 to great acclaim, in a way completing his acting circle.

Gareth Hughes starring as Shylock

His work, though, with the religious drama, had a profound effect on Hughes. At the end of the 1930s he experienced a very real, Saul of Tarsus moment.

He felt a very deep calling to serve God. He even declared anger with God and "rebellious that God had not called him sooner to go into the longing": into the pain that devotion to God demanded.

Hughes was baptized and entered holy orders. His former life, in the eyes of his fellow postulants and seniors, made him utterly unsuitable for the cloth.

He struggled but persevered and, finally, was asked to become a missionary with the Order of the Holy Cross at Nixon, Nevada, on the Pyramid Lake Indian Reservation. He was now Brother David.

His last nod to his former life was as Welsh dialect coach to Bette Davis and others on The Corn Is Green. From that moment on, he became besotted with his Paiute Indians.

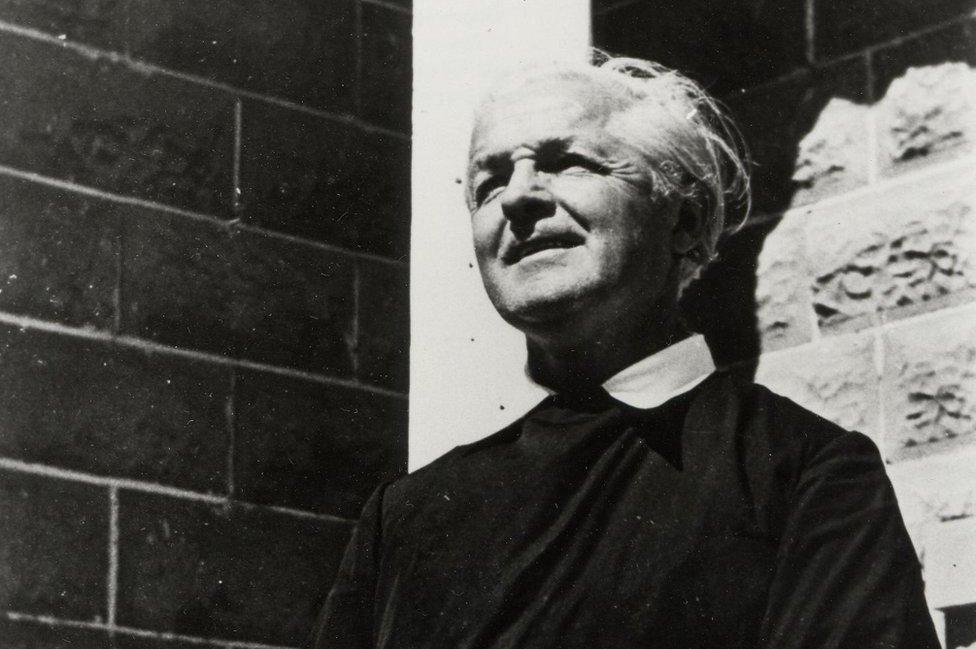

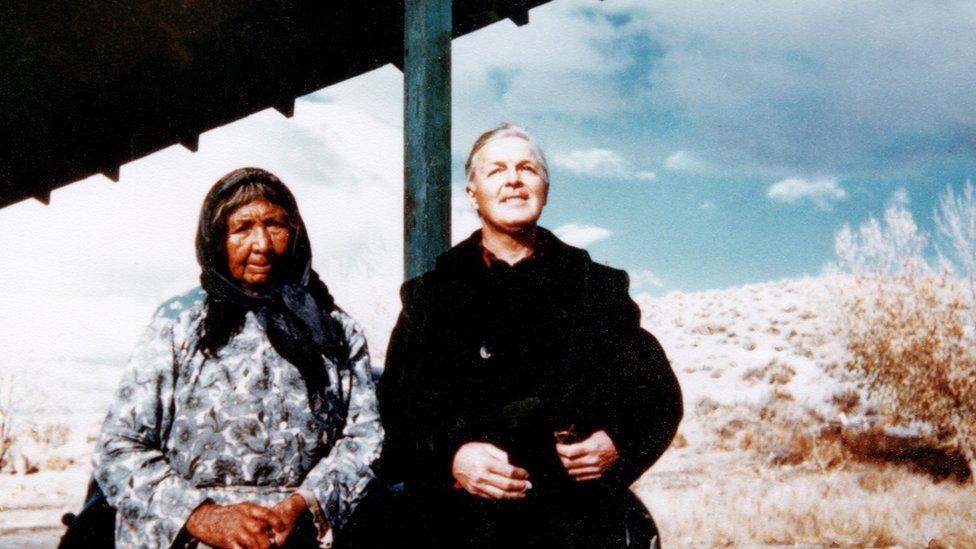

Gareth Hughes with Bishop Lewis

'Unreserved affection'

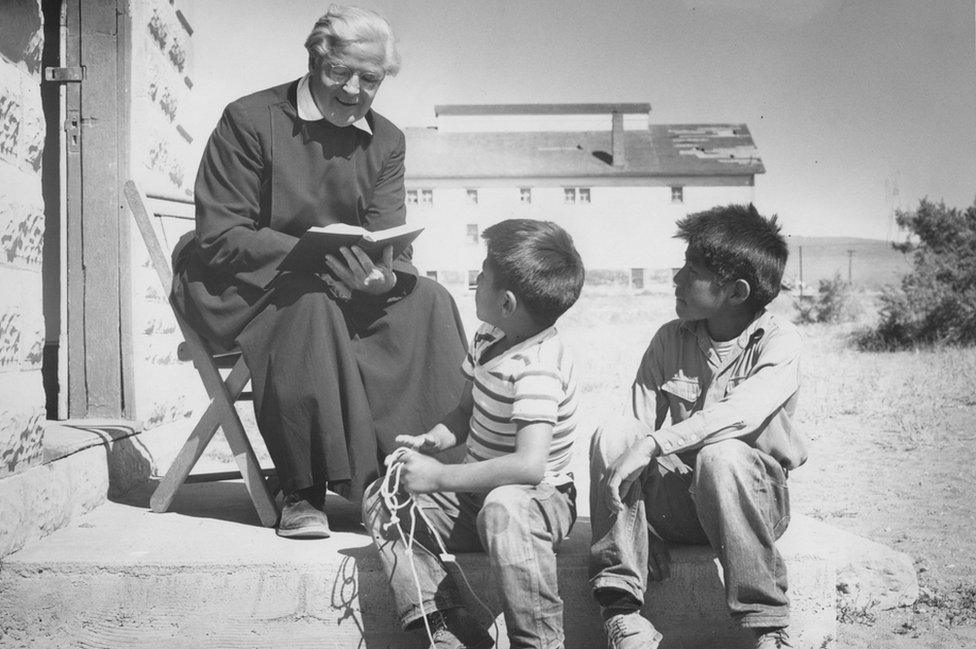

For the next fourteen years he devoted himself to providing a humanitarian mission to the Paiutes.

His journey involved rejection of his employers, hardship and sacrifice, abuse and hatred and a commitment to serve on his terms and no other.

Bishop Lewis, in charge of the Protestant Diocese of Nevada wrote of Brother David: "He is the only white man I have ever known who seems to win immediately the unreserved affection of the Paiute people.

He scolds them, cajoles them, and he is fiercely partisan in their behalf. He is the most effective teacher of the simple essentials of the faith I have ever known."

If ego be a sin then we must forgive Brother David the ego which was a part of the baggage of his former life.

He himself believed that every part of his previous life had been merely a grounding and knowledge which allowed him to serve God.

Although he made serious enemies with his maverick approach to the teaching of the Christian beliefs, his ability to mix his Christianity with the ancient native American beliefs endeared him to the hearts of the Paiutes way beyond his tenure.

Over 40 years after Hughes left the reservation, a display cabinet in the Nixon Church Hall contained newspaper photos and clippings about him, nothing more.

The Paiute children he taught at Sunday school still talked of him as someone who treated them in a way no other white man had dreamed of. His legacy was tangible in an unmistakeable way.

A nurse who witnessed his kindness to a suffering child in hospital, when he himself was suffering, said of him "he traded the glitter for the pure gold".

In 1958, ill health led him to retire to Llanelli, but after years living in the desert he could not settle.

He took up residence at The Motion Picture Home and Country Hospital in Woodland Hills, California, a beneficial institution his years in the film industry allowed him to enjoy.

He lived out his days and officiated as an unofficial chaplain at the home, always in touch with his Paiutes, and died there in 1965 of byssinosis, fibre on the lung, caused by sorting the clothing sent by his old Hollywood comrades and others to help the plight of his beloved Paiutes.

William John Hughes, who was Gareth Hughes, who was Brother David, was one of the most extraordinary Welshmen to ever live.

Brother David at Nixon Cemetery

- Published21 August 2010