How art legacies helped Swansea's Glynn Vivian gallery

- Published

Watch how three benefactors shaped Glynn Vivian art gallery's collection

The richness of an art gallery's collection is in part related to the wealth and generosity of its benefactors - and Swansea's Glynn Vivian gallery is no exception.

While National Museum Wales can thank the remarkable Gwendoline and Margaret Davies, two daughters of a Powys industrialist, Swansea can look to a Welshman, a Frenchman and a Scot.

The legacies left by these three figures have been important to the gallery's collection over the last 100 years.

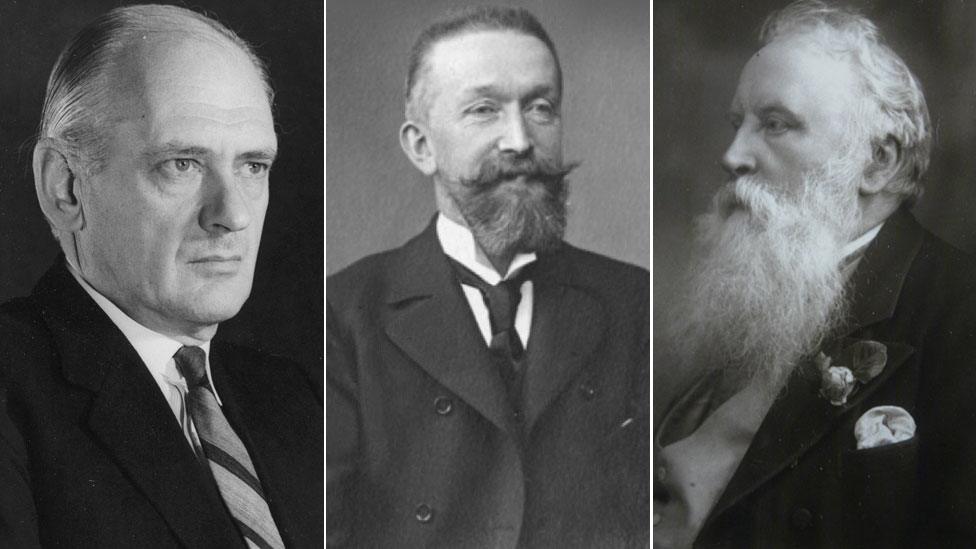

Benefactors: Sir Alex Gordon, François Depeaux and founder Richard Glynn Vivian

Richard Glynn Vivian - who built the gallery but did not live to see it open - donated works to start its collection; François Depeaux, a patron of Claude Monet who had a coal mine in the Swansea valley, donated some of his huge collection of Impressionists; and in modern times, the architect Sir Alex Gordon, who designed Swansea Crown Court among many notable modern Welsh buildings, bequeathed 34 works from his modern art collection.

Who were they?

Richard Glynn Vivian (1835-1910)

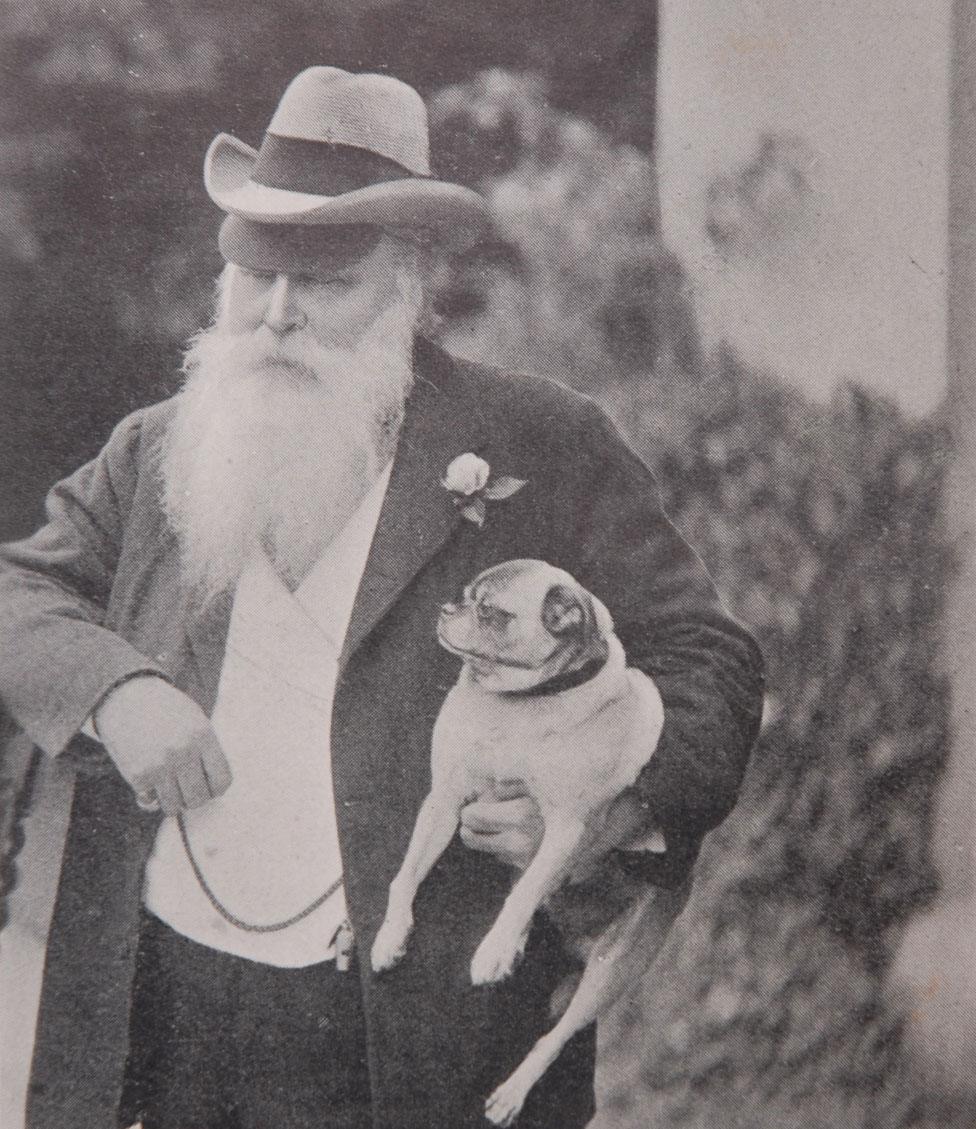

The lifelong art lover suffered blindness near the end of his life

The fourth son of Swansea copper magnate John Henry Vivian, Glynn Vivian had no interest in the family business. But its wealth allowed him to indulge his love of foreign travel and art, which intensified after a short-lived, unhappy marriage.

He was a patron of the French painter and illustrator Gustave Doré and travelled the world collecting works, but also sketching and keeping detailed diaries - all now with the gallery.

One two-year trip from 1869 took Glynn - as he was known - across America and then he set sail from San Francisco to Japan, China and on to Indonesia, Australia and New Zealand.

Glynn was a humanitarian and unlike many from his era, was not an imperialist.

"He abhorred European dominance of these cultures - and in this way he was ahead of his time," said Glynn Vivian gallery curator Jenni Spencer-Davies.

"Glynn was a people person. He was very interested in photography too but it wasn't landscapes, it was in photographing ordinary people."

In his 60s he returned to Swansea to buy Sketty Hall and transformed it into a home for his collection of paintings, watercolours and prints, but also ceramics, glass and books.

Landscape with Shepherd by David Cox

Life studies by Caravaggio - donated by Richard Glynn Vivian

In the last years of his life, nearly totally blind, Glynn offered to leave his art collection to Swansea and build a gallery for it. He laid the foundation stone but did not live to see it open.

He died at his mansion near Victoria in London in 1910 and left a fortune, worth £30m in today's money. His will included generous provisions for the females of the family - traditionally forgotten in inheritance.

Glynn Vivian loved Dutch artist van der Helst's work but it was only 65 years after his death that the gallery managed to buy a painting by Rembrandt's contemporary

As well as his art, his legacy also included a home for the blind and school for the deaf in Swansea, while leaving a network of refuges for miners across the world.

"Glynn did a huge amount of good really," said Ms Spencer-Davies.

The re-opened gallery will include a permanent display, and an app, taking you on a journey through his life and art.

"He inherited his love of art from his father, who died when he was 15," she added.

"Art changed his life and he bought art in the hope it would change others' lives."

Francois Depeaux (1853-1920)

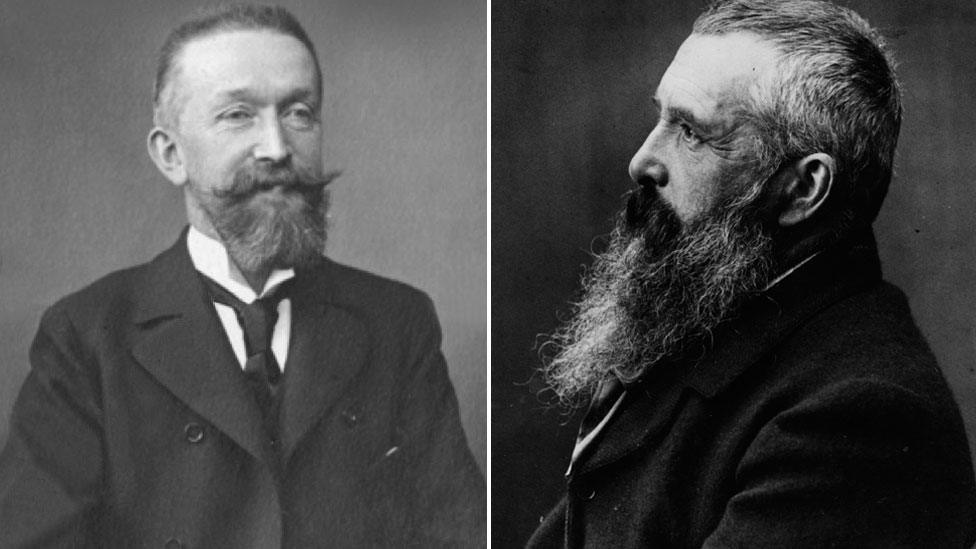

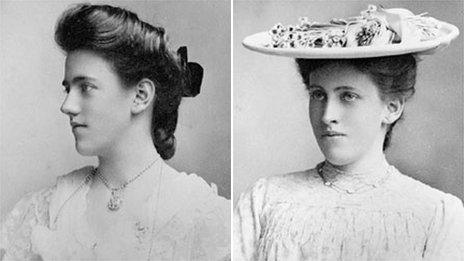

Francois Depeaux (left) was a patron of renowned French Impressionist painter Claude Monet

A coal trader and industrialist from Rouen, Francois Depeaux first visited Swansea in the 1870s, when he was in his 20s. He opened offices in the town and later took over a mine at Abercrave in the Swansea valley, which at one time employed 250 men.

Aside from business, Depeaux was a Renaissance man - an art lover, writer and inventor. He was friend and patron of painters Claude Monet and Alfred Sisley, crucially encouraging the latter to visit south Wales to work.

At one point he had a collection of 600 paintings and supported artists back in Rouen by buying their work.

A Wharf on the Seine at Dieppedalle by Albert Lebourg was donated by Depeaux

View of Rouen through an Apple Tree by Charles Frechon

Vieilles Maisons by Joseph Delattre, a gift by Depeaux a year before he died

His collection also included work by Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec and Gauguin.

But a divorce forced him into splitting up the collection - although he tried to buy some back as they were sold off - and also led to the sale of his Swansea mine.

He knew the Vivian family and after the gallery opened, he donated eight paintings and loaned others.

"He was an amazing person really," said Ms Spencer-Davies.

"Depeaux became one of France's biggest collectors of art, he was supposed to have had 34 Monets. But later he went bankrupt."

Sir Alex Gordon (1917-1999)

Sir Alex Gordon was known for sober suits and precision in his work - and left a personal collection of modern art to his adopted city

Born in Ayr, Alex Gordon moved to Swansea as a boy and worked with Dylan Thomas on the school magazine at Swansea Grammar.

After serving as a major with the Royal Engineers in World War Two he studied architecture. His career would lead to him forming his own award-winning practice and he left his signature on many notable public buildings in south Wales - including Swansea's crown court and telephone exchange and in the Welsh Office building and Sherman Theatre in Cardiff.

Like Glynn Vivian 90 years before him, Gordon also suffered from blindness in his final years. As an art collector, he left paintings to the Friends of Glynn Vivian gallery, including works by Marc Chagall, Augustus John, Kyffin Williams and Barbara Hepworth.

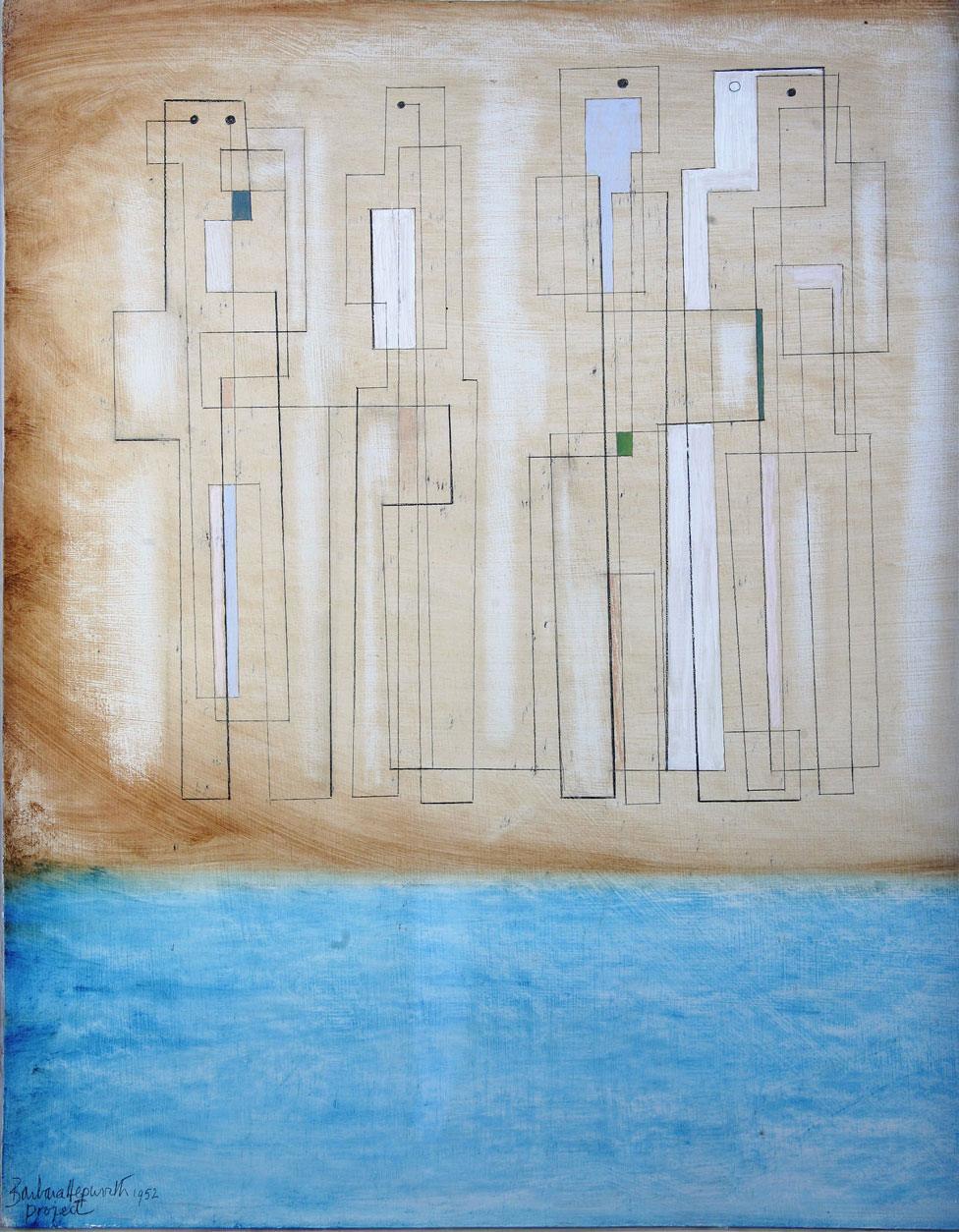

Project (group of figures for sculpture), 1952 by Barbara Hepworth

Ms Spencer-Davies said Gordon had apparently been "inspired" to become an architect after visiting the Glynn Vivian gallery as a young man.

"There is a domestic scale to the work he collected and you can imagine them all around his house. He collected the likes of Kyffin Williams and Gwen John. The Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson are both from 1952 when they were at St Ives, and they're exquisite abstracts."

She said the re-opened gallery was built on legacies of these and other art lovers but particularly of Glynn Vivian himself - whose story will be told in a display dedicated to his collection.

From 18th Century Italian oil paintings to a particular love of ceramics, Glynn Vivian brought the world - and different ages - through its arts and crafts to Swansea but his spirit and attitude is something the gallery is keen to foster as it re-opens.

"It wasn't collecting art for its financial value, but for what it was," said Ms Spencer-Davies.

"It was also the design of things. Glynn was inspired by art and inspired others and he would hope it would continue to bring people together."

- Published14 October 2016

- Published25 August 2016

- Published25 November 2014

- Published20 March 2016

- Published27 January 2014