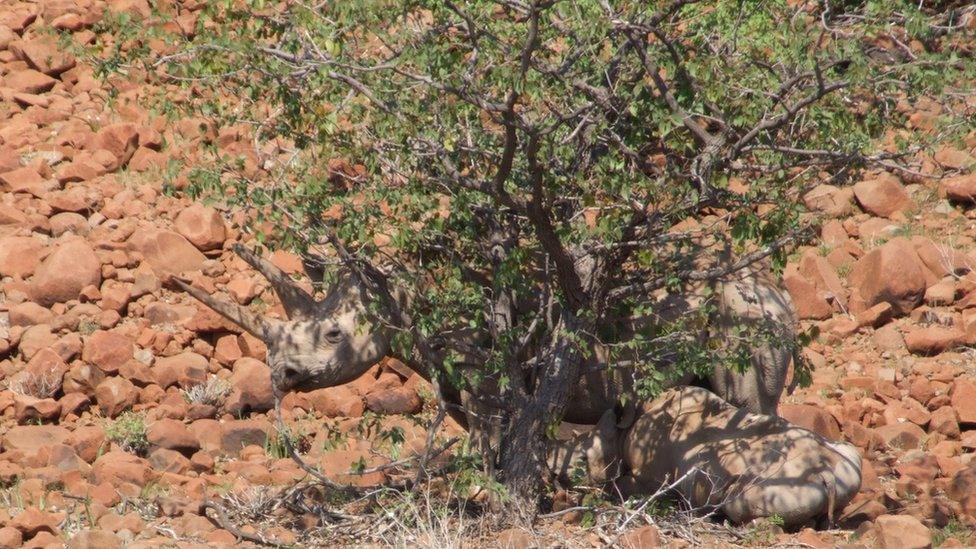

Black rhino: 'New plan' to help save endangered animal

- Published

A new approach is needed to help save the black rhinoceros from extinction, a study involving Cardiff University scientists has found.

Researchers found 70% of the rhino's genetic diversity had been wiped out over the past 200 years due to hunting and loss of habitat.

This means the small number left would be vulnerable to the same diseases.

Prof Mike Bruford said moving bulls to new parks to boost diversity could help combat this "unfolding catastrophe".

From a population in the 1970s of almost 70,000, there are now about 5,000 black rhinos in the wild - the World Wildlife Fund lists the animal as critically endangered, external.

The animal now only survives in South Africa, Namibia, Kenya, Zimbabwe and Tanzania.

Working with colleagues from universities in South Africa, Kenya, Copenhagen and Chester, Cardiff's team compared the genes of living and dead rhinos by visiting museums and herds in the wild.

They found that 44 of 64 genetic lineages no longer exist, which poses a threat to the future of the animal.

Prof Bruford, from Cardiff University's School of Biosciences, said: "The magnitude of this loss in genetic diversity really did surprise us - we did not expect it to be so profound. If you don't have genetic diversity, you can't evolve.

"The new genetic data we have collected will allow us to identify populations of priority for conservation, giving us a better chance of preventing the species from total extinction.

"You could bring a new bull in or swap bulls between parks - you know they're not related so you're bringing fresh genes into the park."

Other suggestions to help conserve the black rhino includes moving animals together to make it cheaper to protect the dwindling population.

The research 'Extinctions, genetic erosion and conservation options for the black rhinoceros' has been published in Scientific Reports., external

- Published9 February 2014

- Published10 November 2011

- Published9 October 2016

- Published9 March 2016