Prince Philip: The Duke of Edinburgh and Wales in light and dark times

- Published

A look back at Prince Philip's legacy in Wales.

Whenever the Duke of Edinburgh visited Wales with the Queen, protocol dictated that he walk two paces behind her.

To the crowds that lined the streets to greet them, this practice perfectly demonstrated his steadfast duty as royal consort. But it also belied the work he did in Wales independently of the monarch.

It was on his wedding day in 1947 that the duality of his role in Wales was made official.

That day, his father-in-law King George VI bestowed on him the title of Duke of Edinburgh. But what few people know is that he also made him the Earl of Merioneth.

Prince Philip was given his Welsh bardic title 'Philip Meirionnydd' by the Archdruid of Wales at the National Eisteddfod in Cardiff, 1960

His primary duty may have been with the Queen, but Prince Philip was determined to carve out a role for himself and the influence of that role was felt widely across Wales, at times not in the most conventional or obvious of ways.

His presence in the immediate aftermath of the Aberfan disaster in 1966, for instance.

His keen interest in the UK's first Outward Bound centre set up in north Wales was said to have been the inspiration behind the Duke of Edinburgh's Award scheme, which he founded in 1956 and has since expanded into 140-plus nations around the world.

But during those early official visits and tours of Wales he made alongside the Queen, the Welsh public lining the streets were preoccupied with the burgeoning symbiosis of the young couple's union.

Dame Shan Legge-Bourke, a former Lord Lieutenant of Powys, who is a trusted confidante of the Royal Family and whose daughter Tiggy was nanny to the young princes William and Harry, said: "They worked brilliantly together.

"They were devoted, the one knew exactly what the other's thinking. It was a hell of a partnership. Considering the job that they both did, it was a remarkable relationship."

The Duke of Edinburgh was awarded the Freedom of the City of Cardiff on 2 December 1954

(Left) Shan Legge-Bourke with the Queen in mid Wales (right) her daughter and former royal nanny Tiggy Pettifer with Prince Harry

In 2009, the duke became the longest-serving British consort, the partnership having come into even sharper focus in recent years as the couple reached their 10th decade.

He was - in the Queen's own words - her "strength and stay" during her reign.

"Beforehand they would often do separate trips," said Sir Norman Lloyd Edwards, who in his role as Lord Lieutenant of South Glamorgan from 1990 to 2008, managed countless royal visits to south Wales.

"It was in the last five years or so that I noticed they would go everywhere together. I think it was to give her a hand really.

"She tries not to, but he was always there for her to take his arm, going down steps, things like that. He was absolutely there for her."

The Duke of Edinburgh and the Queen watched the England v Wales women's hockey match at the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow

Queen Elizabeth ll and Prince Philip at the royal opening of the Senedd in Cardiff Bay on 1 March, 2006

Spool back to 1958 and it was quite a different story - the duke was making his own big impact in Wales.

Then he played a central role in a triumphant moment of the nation's recent history when he opened the British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Cardiff.

Former Wales rugby international and Olympian Ken Jones presented the baton to the Duke of Edinburgh at the opening ceremony at Cardiff Arms Park

Many doubted the ability of Wales - the smallest nation ever to host the games - to pull it off.

But as Prince Philip - president of the Commonwealth Games Federation - presided over the games, in which 1,100 athletes from 35 nations competed at Cardiff Arms Park in front of 178,000 ticket holders, Wales was firmly in the global spotlight.

Some heralded the profile and success of the games as marking a sea change in the profile and the confidence of the country, in particular its newly-confirmed capital.

"You have to remember that at this stage Wales had only just got its own secretary of state and Cardiff hadn't long been confirmed as the Welsh capital," said Prof Peter Stead, a cultural and social historian.

The Duke of Edinburgh presented the gold medal to Herb Elliott of Australia on the final day of the Empire Games

"It was only as a result of the success of the Wales team in these games that the government was finally forced to officially recognise the red dragon as the flag of Wales.

"There wasn't the same sort of secessionist spirit here as you had from many of the African and Caribbean nations, but it did give Wales a sense of confidence in our own identity, starting a process which led to the establishment of the national Assembly, and which is still on-going today."

The field of physical endeavour, combined with service to others and personal development in young people, had always been subjects close the duke's heart.

Two years before the games were held, he had established the Duke of Edinburgh's Award scheme for young people.

Former naval officer Prince Philip visited Aberdovey Training Centre in north Wales in July 1949

The awards were based on the principles and philosophy of the UK's first Outward Bound centre, which opened in Aberdovey, north Wales.

It was established in 1941 with the aim of building resilience in young sailors for service in the Merchant Navy, so vital in the war effort.

The centre's pioneer was Prince Philip's mentor, German educationalist Kurt Hahn, who had also set up Gordonstoun School where the duke was educated.

"The award scheme was a good reflection of the values of Prince Philip," said Sir Norman.

"It demonstrated 'stick-ability' - a quality that he felt very strongly about. You had to give it a go and it was hard and there were times you wanted to give it up - you were cold and wet but you kept on with it.

"He was a disciplinarian and not giving up easily sums him up rather well."

Reaction to death of Prince Philip

In stark contrast to the success and celebration of sporting and youth achievement, just eight years later, Wales entered one of its darkest chapters.

The world watched in horror as news began to emerge of the tragic event unleashed upon a small mining village in the heart of the industrial south Wales' coalfields on 21 October 1966.

The duke met rescue workers and miners in Aberfan as people searched through the rubble

A total of 116 children and 28 adults were killed when a coal waste tip slid and crashed down a mountain, engulfing Pantglas Junior School and a neighbouring terrace of houses in the village of Aberfan.

Within hours of the tragedy, Prince Philip's helicopter had arrived. He later said he had never seen anything to compare to the scenes he encountered.

His personal interaction with grieving families and those involved in the recovery operation showed a side to the Royal Family which was not often seen in those days - it was one which was to become more and more prevalent and important as it evolved to resonate with modern-day British society.

The Duke of Edinburgh talked to the police and community in Aberfan just hours after disaster struck

Former royal writer and broadcaster Brian Hoey, then a newspaper reporter in Wales, was among the first journalists to arrive on the scene.

"Prince Philip came as an advance party on the Saturday morning and quietly moved among the villagers offering words of condolence before returning to Buckingham Palace and telling Her Majesty it would be more appropriate for her to wait," he said.

"He was briefed on the problems facing the recovery operation, which it had now become, again insisting on a total absence of protocol."

Jeff Edwards MBE accompanied the Queen during her fourth visit to Aberfan as part of her Diamond Jubilee tour of Wales

Just over a week later, he escorted the Queen in what was to become one of the most poignant and tragic royal visits of her reign.

"Both royal visits were very much appreciated by the people of Aberfan, for their compassion and approachability, and for showing that they cared," Mr Hoey added.

Jeff Edwards, the last child to be pulled out of Pant Glas School alive, said: "The Queen and Prince Philip went into a nearby house after visiting the cemetery where the children were buried.

"She was really upset and she had to compose herself before she went on to meet the families who had lost children and relatives.

"I remember being told that the duke was offered a Welsh cake made by Mrs Jones who lived in the house.

"He told her they were the best Welsh cakes he'd ever tasted. And from that time everyone in the village would say Mrs Jones, who used to live next door to us in later years, made Welsh cakes fit for a queen."

The Queen and Duke of Edinburgh officially opened Ynysowen Community Primary School in Aberfan in 2012

The Queen's Diamond Jubilee celebrations marked the royal couple's fourth and final trip to Aberfan, a community they shared a special connection with

Mr Edwards, who went on to become mayor of Merthyr Tydfil, met the duke during a further three visits he made to Aberfan.

"He struck me as incredibly knowledgeable and thoughtful," he recalled.

"And with a great sense of humour. I was showing him round a pharmaceutical company, Simbec Research, in Merthyr one time.

"He turned to me and said 'Simbec? Wasn't that the company which did the heart tablets?' I told him yes, he was correct, and that they'd also made Viagra. 'Oh really?' he said with a wry smile. 'Oh, we'll keep that one quiet'."

The Duke of Edinburgh with Sir Norman Lloyd Edwards at a royal gala at the Wales Millennium Centre, Cardiff, in 2004

Dame Shan said he was "marvellous at chatting up people" and had "a terrific sense of humour".

She added: "We knew he was renowned for his 'interesting' remarks but he really was brilliant at making people feel at ease.

"He was especially interested in the young, whether it was the cadets, scouts, that sort of thing, he was extremely relaxed. During a visit to Welshpool, I recall him spotting a group of Army cadets and he made a beeline for them.

"Or he'd notice someone in the crowd who'd just been shopping and were carrying a dustpan and brush. He'd spot that and go and speak to them."

At times, the lighter side of the royals' public engagement spilled over into the familiar territory of those so-called "interesting remarks" the duke became famous for.

The Duke of Edinburgh and the Queen attended the opening of Cardiff University's Brain Research Imaging Centre in 2016

In fact the earliest recorded public gaffe was made in Wales.

It was in June 1956 when the duke arrived at the Plas-y-Brenin mountain centre and a reporter from the North Wales Weekly News was among the assembled crowd.

Sir John Hunt, leader of the first successful Everest expedition, was an instructor at the centre and he introduced Prince Philip to ex-servicemen of the British Legion.

"Is everyone here called Jones?," he exclaimed, referring to Wales' most common surname.

Crowds of schoolchildren greeted the Queen and Duke of Edinburgh on the seafront of Llandudno, during a two-day visit to north Wales in 2010

The reaction was good humoured, the North Wales Weekly News reported, as it was pointed out that there were a few Williams, Roberts and Evans there too.

This was the start of a series of faux pas to make headlines during the duke's long life, including one when he met an Eastern-style dance group in Swansea in 2008.

The Duke of Edinburgh joked with the Eastern dance group during a visit to St Thomas Community Primary School in Swansea

Beverly Richards, who was part of the Suhayla Dancers, said: "Prince Philip said 'I thought Eastern women just sit around smoking pipes and eating sweets all day'.

"I said 'we do that as well' and he looked us over and said, with a twinkle in his eye, 'I can see that'.

"We were stunned, then we all burst out laughing... We were not insulted. I think that it's great that he said it. He was very down-to-earth."

In 2016, he made headlines again - this time during a visit to open the Cardiff University Brain Research Imaging Centre.

The Duke of Edinburgh with the Queen at the royal opening of the fifth session of the National Assembly for Wales in 2016

The duke - visiting the city with the Queen, the Prince of Wales and the Duchess of Cornwall for the opening of the fifth session of the National Assembly for Wales at the Senedd - was introduced to a group of school children.

"He asked us if we could speak Welsh," the children recalled, "and we said yes.

"He said: 'You must have really good brains to speak Welsh'."

But his joke, and any offence it might have caused, must be seen in the context of the support and respect he had afforded the Welsh language.

Prince Philip was the one who encouraged a young Prince Charles to learn Welsh while studying at Aberystwyth University.

The Duke of Edinburgh at Aberystwyth in 1973

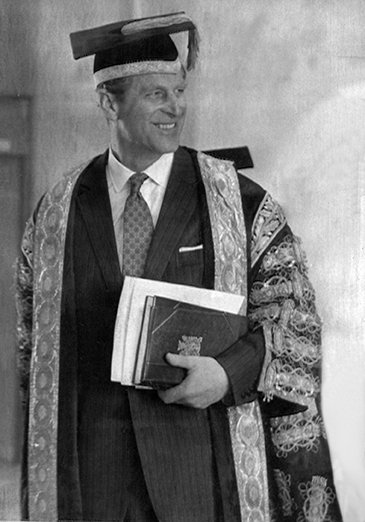

The duke later said it was his role as chancellor of the University of Wales, in Bangor, which he held between 1949 and 1976, that made him realise the importance of the language and culture to many Welsh people.

On that occasion, Princess Elizabeth, the future Queen, walked behind her husband, who led the procession into the stately, oak-panelled Prichard-Jones Hall.

Giving a speech on the importance of university education in post-war Britain, Prince Philip spoke in Welsh as he awarded honorary degrees to his wife, Prime Minister Clement Attlee and actor Emlyn Williams.

In a speech at Aberystwyth University in the 1970s he said: "I find it rather difficult to realise that I have been chancellor of the University of Wales for 25 years.

"But I do know that it has been long enough to begin to appreciate some of the qualities of life in the principality that are so much cherished by Welshmen.

"And this really was one of the reasons why I encouraged my son to spend at least part of his time as a student here in Aberystwyth."

The duke and the Queen with Prince Charles at his investiture in Caernarfon Castle July 1969

Prince Charles studied Welsh and Welsh history and culture in Aberystwyth, leading up to his investiture at Caernarfon Castle in July 1969.

It was hoped that he would become a role model for youth at a time dominated by hippies and the "summer of love".

During the 1970s and 1980s, the duke was a regular visitor to Wales. But it was perhaps with the dawning of devolution that his role in Welsh public life took on new significance.

In May 1999 he arrived in Cardiff with the Queen at Crickhowell House, where the Queen signed a special edition of the Government of Wales Act, which symbolised the transfer of powers from Westminster to the Welsh Assembly.

In June 2006 the royal couple came to Wales to open the new Welsh Assembly building, when it moved to its current home, the Senedd.

Attending all five of the official openings of the Welsh Assembly - which is now called the Welsh Parliament - with the Queen, as well as more low-scale visits, the duke's busy schedule continued into old age.

A proud grandfather, the duke visited Prince William's search and rescue base at RAF Valley, Holyhead

The duke shared a joke with his grandson, Prince William, during the official visit to RAF Valley in April 2011

And with that old age, the more robust side of the duke's character had perhaps taken on a gentler nature.

"I think he mellowed in his old age," Dame Shan said. "He was still impatient, but not so impatient as he used to be.

"Irascible? Yes, that's a very good word. You needed to watch your 'Ps and Qs' and if you brought up a subject or talked to him about something - if you got it wrong - he would say 'you're completely wrong on that' and explain exactly why you were wrong. He was incredibly well-informed."

There is perhaps one anecdote, told by Sir Norman, that more than any other sums up the duke's down-to-earth, inquisitive, informed and, at times, mischievous character.

Sir Norman had been escorting the Queen and Prince Philip for the first opening of the Welsh Assembly on 26 May 1999.

"There was so much happening that day, a big concert, cocktail party in St David's Hotel which was followed by a very select dinner party," he explained.

"At the dinner party there were four tables, with about eight people or so on each. The Queen sat on one, the Duke of Edinburgh on the other, Lord Dafydd Elis-Thomas as presiding officer on the third and I was on the fourth.

"A lady sitting next to me said 'anyone know what's happening to the soccer?'

"I said I didn't have the foggiest idea. 'Oh', she said, 'there's a big match tonight - Man U against Bayern Munich in the Champions League final'.

"I summoned a young waiter and asked him if he could find out the score. He came back and said the Germans are leading 1-0. A short while later he came back out and said Manchester United had equalised. Then five minutes later, Man U had scored again, the game was over and they'd won.

"I said 'are you sure?' He was only a young chap, maybe his first job as a waiter. He looked worried but said yes he was sure.

The Duke of Edinburgh appeared at the opening of the fourth session of the Welsh assembly in June 2011, three days before his 90th birthday

"So I said to him: 'Will you go and tell the Duke of Edinburgh?' He looked terrified and said 'what do I say?

"I said 'just say excuse me sir the lord lieutenant has asked me to tell you that Manchester United have won the European Cup' And so he went off looking grave, rehearsing the words under his breath.

"I saw him address the duke and the relief on his face was palpable having delivered the message. 'Oh splendid!' the duke exclaimed. 'Please go and tell the Queen.'

"That poor young man. His face was a picture."

The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh toured RAF Valley, Anglesey, in 2011

Held with affection by many for his humour, his character was just a small part of the unstinting contribution and legacy remembered by so many across Wales.

His constant support of the Queen, the work he did here independently of her, at times out of public view, demonstrated time and again that he was a man who led by example to uphold his firm belief that duty and service were cornerstones of the monarchy.

Children looked through a marquee window to see the duke and the Queen at the Diamonds In The Park festival in Glanusk Park in April 2012