Ian Puleston–Davies on his obsessive compulsive disorder

- Published

Obsessing about a stain on a piece of paper or fearing he will injure himself by sitting down is part of every day life for former Coronation Street actor Ian Puleston-Davies, who has Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. This is his story.

Sometimes a simple question can have more than one answer. For me, it's: "So when did you know you had OCD?"

The obvious response is I was diagnosed at 35 when I went to get some help with a condition that had become so disabling I was struggling to get out of bed in the morning, for fear of breaking my neck.

But the real answer is, I'd known I was different from as early as seven years old. And there's one particular memory that's become stamped in my mind.

I grew up in north Wales in the town of Flint and have happy memories as a school boy at Ysgol Gwynedd. But it was also where I started to show signs of OCD.

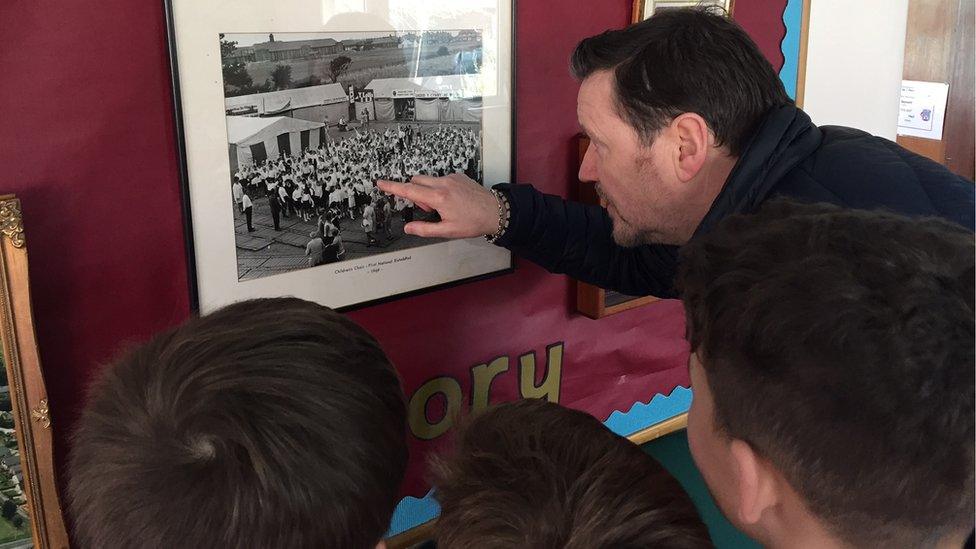

Filming with the BBC, I went back to my old junior school for the first time since I'd left. The memories came flooding back.

Walking the corridors, there were the pictures of the old head teacher, and then I came across a photograph from 1969 and there I was. I'm part of the school Eisteddfod choir and we're waving up at the photographer up on his ladder.

I'm waving, but I'm the only one not looking at camera - my eyes are down - probably worrying about some small thing - OCD captured in time.

The playing fields where I used to kick a ball around with my mates are also still there.

I loved football but for some reason, every time I was passed the ball I would anxiously check the flies of my shorts to make sure they were done up.

You can't help noticing something like that, and I stood out. Back then, of course, I just thought I was a bit odd. Now I realise that my "habits" were in fact my OCDs.

Actor's first memory of OCD 'playing football in school'

Here's another question - what exactly is OCD?

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder can be a seriously disabling condition. It's a clinically recognised disorder and those with OCD experience intensely negative and intrusive thoughts that cause huge anxiety.

That's the obsessive bit. Then in order to quell the thought or quieten the anxiety, we repeat an action again and again. That's the compulsion.

OCD can vary a great deal. It's not all about washing hands. For me I can obsess about anything, from a stain on a piece of paper to the fear I'll injure myself simply sitting down.

Then I'm compelled to do some mental checks, or perform careful rituals to quell my anxiety.

There's part of me that knows my fears are irrational, but that doesn't help. Once I've got a thought in my head, I just keep over-thinking it.

Actor with OCD 'fears injury when sitting down'

For years I couldn't go to the cinema because I'd be obsessing about why a couple sitting behind me had decided to watch that film that night, why he chose that tie, what was in her handbag, where were they going to eat later, and so on and so on.

It feels a bit like my mind is like a whale catching all the krill. The krill being the thousands of thoughts that go through our minds every day.

Most people let them slip away, but when you've got OCD they get stuck and your mind can be a blur trying to analyse it all.

Over the years I've had help and learned to manage it, but it can still get very noisy in my head.

I'm not alone. It's estimated between 1% and 2% of the population have OCD, although I think the figure could be higher.

Compulsions can be embarrassing, and we all go to great lengths to hide them. OCD is not nicknamed the "secretive disorder" for nothing.

Treatment for OCD

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is the treatment recommended for OCD in the NICE Guidelines, external

The British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy (BABCP) is the specialist body for accrediting CBT therapists

There are 89 BABCP accredited CBT practitioners in Wales, compared with 4,623 in England - that means there are three times as many accredited CBT practitioners per head in England as Wales

Of the 89 in Wales, 33 work for the NHS, the rest are private

No health board in Wales currently uses private CBT practitioners to treat OCD patients

The Welsh Government has invested £3m in the past two years specifically in psychological therapies such as CBT for adults

The good news is there is help for OCD. NHS guidelines recommend OCD should be treated with medication and therapy.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy or CBT is the type for OCD. Research suggests 75% of those who get it see big improvements.

It is available on the NHS, but while I was filming in Wales I heard a lot of stories of people saying it's hard to get the right level of help.

I also discovered there is a shortage of accredited CBT therapists. That's so frustrating because I know how OCD can take over your life.

If there's treatment out there that offers a good chance of overcoming or even just managing OCD, then I think people wherever they live should be given the chance of trying it.

While filming I met some very brave people and their families who agreed to talk about how OCD had had a negative effect on their lives.

I met people whose rituals took up 90% of their day, and those who had been driven to despair.

They were stories I recognised myself and I really felt for the people I met.

I think things are changing, but I don't think people quite realise how far OCD can affect people and their families, and I hope this film will at least raise awareness about that.

OCD - An Actor's Tale is available to view on BBC iPlayer

- Published27 March 2017

- Published10 March 2017

- Published29 November 2016

- Published16 June 2016

- Published3 December 2015

- Published3 December 2015

- Published30 July 2013