Lessons from Lansbury Park - 'Wales' poorest estate'

- Published

- comments

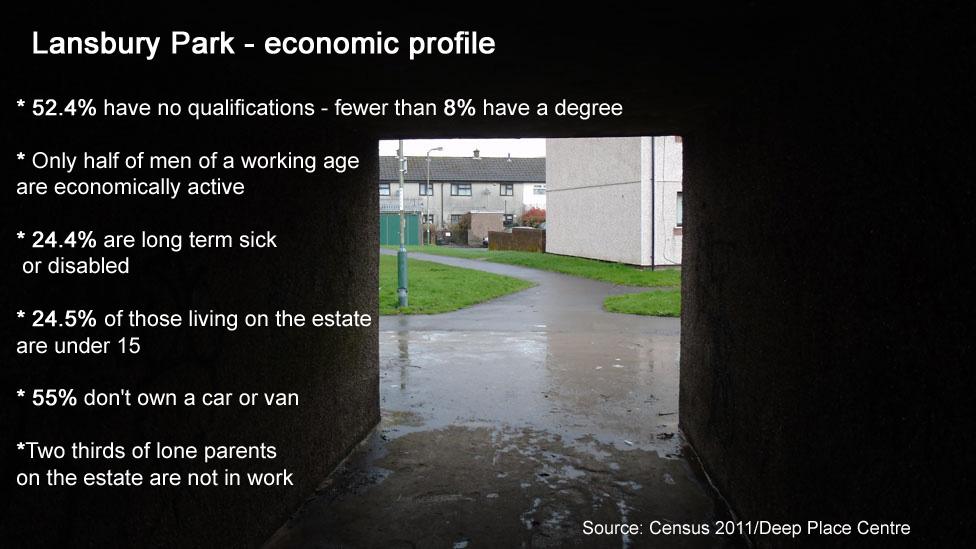

It has already lived with the label "Wales' most deprived area" for the last two years.

Now major economic research centred on Lansbury Park in Caerphilly suggests that there needs to be fresh thinking about how we tackle the poorest places in Wales.

As would-be councillors campaign to be elected, these are challenges that local authorities cannot simply solve on their own.

Dr Mark Lang explains why Lansbury Park still feels isolated despite the work that has gone on

Poverty is on the increase in Wales amongst children, working age adults and pensioners, despite attempts to reduce it over decades, according to the Bevan Foundation think-tank. , external

It calculates that dealing with the consequences of poverty is now costing the Welsh public purse £1 out of every £5 it spends.

Those findings are now swiftly followed by a report into Lansbury Park, which advocates a new approach but no magic wand.

It is nearly 25 years since a range of social and economic problems were first highlighted by research on the estate, which lies just a mile from Caerphilly town centre.

More recently, Lansbury succeeded part of Rhyl to a title no one wants - officially ranked as Wales' most deprived community.

If you walk through the estate - home to 2,200 people - very little has changed on the surface from how it looked decades ago.

Lansbury was named after a Labour leader of the Depression era when it was built in the 1960s and Attlee Court in the middle is among reminders of other figures from the party's past., external

Caerphilly council since 1996 has been under both Labour and Plaid Cymru control.

This "deep place" study was commissioned by the local authority and its analysis does not apportion blame - only recognising the approaches of a generation or more have simply not worked.

Despite money being spent, and a Communities First programme running, economic and social problems have become "embedded".

Dr Mark Lang spent six months working on the Lansbury Park "deep place" study, with Prof Dave Adamson, who led the original research in 1993.

Beyond the stark economic statistics, the research looks at less tangible but equally relevant factors.

Indeed, the "feel" of the place is possibly as much of an obstacle to progress.

The "sterile" urban landscape, the lack of trees on the little green space the estate has, are all features; horizons are limited, physically and emotionally.

So as new councillors are soon elected across Wales, are there lessons for similar urban areas too? Especially at a time of austerity, council budget pressures, uncertainty over filling future gaps left by European funding and the forthcoming overhaul of Communities First.

Dr Lang believes it is about understanding the specifics of a place - and spending what money there is, more wisely.

"With some of the funded activities, I feel, they don't take the community out of itself; they don't encourage people to leave their communities and do something somewhere else, experience a broader world," he said.

"It might well be you spend the same money on supporting activities but you spend it differently, more intelligently.

"If you take people out of their community and engage in activities not inside it, you can broaden people's horizons and aspirations.

"That in itself will lead on to people wanting to gain more skills and better skills. We need to break through those barriers."

Engaging hard-to-reach men in their 20s and 30s is the biggest challenge for those already running programmes to get people both fit and into work.

Even the "stick" of recent welfare reforms has not had a spike in more people joining programmes on the estate, compared with other parts of the town.

Those that do are helped towards interviews in construction, security and call centre work. Cardiff is only 40 minutes away by train and groups have been given work experience as part of their training.

The low level of educational attainment - more than half of 16 to 64-year-olds without any qualifications - is a worry if Lansbury is not to stay at the back of the queue.

More than half the pupils at the local primary school, St James, qualify for free school meals and last year's inspection report found overall it was "adequate", external but called for an improvement in reading and writing standards, as well as attendance and punctuality.

There is a new head teacher in charge but the challenge is continuing and goes beyond the classroom.

The visual impact of the estate is something all are conscious of. There is something of a time-warp about the 1960s flats and homes, all in uniform colour.

That is changing with a £10m housing programme over the next 18 months, which includes 320 council properties getting £2m of new external cladding.

Another £500,000 will go on environmental improvements and demolition has started of an "eyesore" footbridge.

Lorna Wellington and Heidi Wilkie talk about what the Lansbury Park Estate needs - and what the community provides

Sian Denatale has lived at Lansbury for 18 years and four of her five children still live on the estate. One works part-time for a retailer and another works in a nearby food factory.

"It has changed a lot - for the better," she said. "There's a massive sense of community, everyone pulls together. But we need help to improve the area like they're doing with the housing.

"Parks and a resource centre would be nice, an internet cafe for the older children - they go up town, hanging around the streets and the station, anything could happen."

Lorna Wellington, who grew up on the estate from the age of seven, moved to live a mile away but still comes back for an exercise class at the community centre and most of her friends are still on the estate.

"Lansbury's had a bad name for many, many years but you are who you are - there are other places just as bad," she said.

Heidi Wilkie added: "It's unjustified. I never felt lonely, there was never that isolation, you always had someone to fall back on, you could always walk down the street and knock on someone's door."

Council officials accept Dr Lang's findings and said all organisations involved have to adopt a mature approach, recognising past failures.

It was not just about more money and investing in buildings but focusing support on making an impact on people themselves.

"It's a cycle, if people say you're not good enough, you believe you're not good enough, and around it goes and we have to intervene," said Christina Harrhy, Caerphilly Council's corporate director for communities.

"The jobs and opportunities are out there, it's a fantastic location and with transport infrastructure changes we're going to be more accessible to Cardiff and the wider region - this community just needs the belief in themselves."

Work on improving the estate - mostly council homes - includes internal and external work

The report makes 22 recommendations, which includes offering learning opportunities outside the classroom and chances for young people to widen social horizons.

It also suggests involving the whole community in activities - not just singling out disadvantaged groups.

The phasing out of Communities First - but with legacy funding of £6m from 2018 - reflected a view from a significant number that far-reaching reform was needed with ministers pointing towards a "new approach focused on employment, early years and empowerment".

Dr Lang said the lesson for Lansbury and other poor areas is that it might take 15 years to make a real impact.

"There's not a silver bullet which will miraculously improve things overnight," he said.

"There's a multiplicity of things you need to do, some small, some big, to assist this community to grow, to re-integrate into the economy and improve household income levels.

"That's not going to happen overnight, it's a long term challenge, a multi-generational challenge and you have to be honest from day one how long it's going to take and the scale of the challenge. If you do that, you can move on."

Twelve candidates are standing in the local elections for the St James ward, external, which includes Lansbury Park.

- Published14 March 2016

- Published26 November 2014