Why I used holiday to understand Greek migrant crisis

- Published

Thousands of migrants have reached Greece via boat crossing the Aegean Sea from Turkey

I'm on a plane to Athens, my stomach churning as I try to focus on what's ahead of me. A few days ago, I made the decision to do this and suddenly here I am doing it.

When I land I will meet a woman called Zena, a refugee from Iraq and for the next few days she will be my host and her apartment will be my home.

I know nothing about Zena only that she is in Athens with her children having gained asylum after escaping the war in Iraq. I don't even know what she looks like and she's meeting me at the airport.

Back at home I'm a journalist, and I process lots of information every day.

Stories from Wales and the world arrive at my desk and I process them and sometimes make them into neat, broadcast bulletins which arrive in your car or home or wherever it is that you like listening to the radio.

The last couple of years the news had been tumultuous; the EU Referendum, American and British elections, terrorism attacks, the war in Syria and Iraq and the refugee crisis.

And so there I was at my desk, looking at the statistics, the numbers, the government responses and watching people from a land far away from my ideal holiday destinations making their way into countries across Europe.

And then suddenly it all becomes a blur and slightly saturated like it does with all rolling news stories.

Nia (left) with Zena who says she still fears for her safety and asked her identity be protected

The words become meaningless because I've read and heard them so much.

Asylum seekers, refugees, migrants - they are just words you are typing and broadcasting - not people with hopes, dreams, fears and children they need to protect at all costs.

As I read and broadcast I realise I really don't understand what's going on from an 'on the ground', the human perspective.

The wars in the middle east and the refugee crisis are bound together and I have this overwhelming need to get to grips with it all as a human being by meeting the people who are being affected.

As Syria and Iraq are out of the question I decide on Greece, and my friend who had volunteered there some time ago puts me in touch with people who can guide me through it all for the next couple of weeks.

Migrants who make it to Greece have often embarked on perilous journeys

I land in Athens and meet Zena. She's slightly nervous as am I and I instantly love her pink and blue headscarf. On the train to her apartment she gives me a run-down of who she is.

Zena comes from a middle-class background and lived a lovely life in a beautiful home in Iraq.

The family were well off with herself and her husband having good jobs that paid well.

Less than two years ago when the war was still raging, the militia knocked on the door of the family home, demanding that her husband join them in their quest.

He refused but they kept coming back and eventually threatened the family.

In order to protect them he left the country and eventually ended up in another country in Europe where he remains while the family await reunification.

But the militia kept coming back to Zena's door and eventually threatened to take one of her teenage sons if she didn't reveal where her husband was.

That night they pack their bags, gather some money, and set out for what was eventually an almost 2,000km journey on foot to the Turkish border in what Zena describes as "the summer of hell" that she can't bring herself to think about too much in fear of sinking into depression.

Children's terror

When they weren't walking and waiting at borders, their homes became make shift refugee camps in the mountains of no man's land.

They would try to sleep, terrified of the dangerous people and wildlife around them.

Each night Zena would pray for her children's safety as they gripped each other's hands in a kind of terror that no child should ever have to experience.

She shows me pictures of these camps and eventually swipes to an image of the unrecognisable, torn and saturated clothes that they lived in for months.

I try not to cry in front of her.

That night is the first of five wonderful nights I spend with Zena and her boys in her small apartment in Athens.

We all sleep in the same room, the boys on the bunk beds, Zena on the floor and myself in the single bed.

While I nod off exhausted after my journey I hear the faint sound of the Minecraft game from the bunk beds.

Zena explains to me that she is so glad this game was invented, because the boys are getting lost in positive worlds of building new lands instead of thinking about the lands they have witnessed.

Over the next few days I visit the voluntary school that Zena has set up in the city to teach English and Arabic to refugee children.

She cooks delicious food and introduces me to her community and the network of people she has created in her new home.

If Wales and the UK was ever under attack and destroyed, I would want refugee women at the helm of building it back up.

I have seen them build schools, kitchens, communities and communication networks out of absolutely nothing except sheer will, survival, hope and love.

Migrants granted asylum will travel through the island's main port of Mytilene to the mainland

When I look at Zena, I don't see the nightmare anymore. I see who she really is; a strong, intelligent and kind woman who has the capability of offering so much to humanity, and I am proud to call my friend.

I'm standing by the port of Piraeus ready to board the ship to Lesvos saying goodbye to Zena.

As I lie on my make shift bed on the overnight journey I realise that my first world problems haven't even entered my head over the last week.

It's morning on the Greek Island of Lesvos and already hitting 30 degrees.

I've come here because this is one of the islands in Greece that saw some of the biggest numbers of asylum seekers land during the initial crisis, and landings are still happening there today.

There were just under 10,000 asylum seekers and refugees there in January this year and each of them, like Zena, with their own individual story of why and how they arrived.

Thousands of discarded life vests in the hills above the town of Mithymna, Lesbos in 2016

My apartment here is the size of Zena's in Athens. At home, I would consider it tiny but now I'm a bit lost without her and the children.

Mytilene is the main port of Lesvos Island and the main route to Athens.

There are many non-government organisations here who provide humanitarian aid and crisis response to the Moria refugee camp which is a few miles away from the port.

I've heard many stories about this camp, how it is essentially a prison and in the past two years it has been set on fire six times during riots.

The organisation I meet with provide legal, medical and housing support to people within the camp and through them I meet Abdullah.

Abdullah is from Syria and came here with his two young children in a story that is not unlike Zena's. However, Abdullah arrived with excruciating tooth ache and has an infection in his mouth which he is still suffering with.

Can you imagine? Having toothache at home is bad enough if you can't get an appointment with the dentist quick enough.

Add 40-degree heat to that, kids who are hungry but you can't afford to feed, no prospects, no job, no hope and a wife who has left you after you've made a treacherous journey to get here for the survival of your family and well - you get the picture.

But he's still smiling. He's smiling because a local organisation has raised the money for him to have the treatment he needs to remove the tooth.

This, he tells me, will at least cancel out one of his problems and greatly improve his mood to face what lies ahead.

It is organisations like this that are so crucial here.

The organisation that I'm spending time with operates from its director's house - a young woman who set it up.

She opens her house up every day to volunteers who come in and take over her personal space to fix whatever problems that have arisen at the camp that day.

Refugee and migrant families walk through the Moria Refugee Camp in 2016

She's constantly on the phone with lawyers, volunteers, refugees and asylum seekers trying her best to iron out all the problems whilst also trying to keep the organisation afloat financially so they can support people like Abdullah.

While they are busy doing all of this I ask how come nobody really knows about the work they do? She explains that no one there is skilled at marketing, communications and social media.

I'm glad she's said this because up until now, except for spending around 200 Euros on ice creams for refugee kids who either hadn't tasted any before or in a very long time - there's not been much else 'hands on' that I've been able to help with.

Within half an hour of that conversation we've set up a social media and communications workshop with the organisation and refugees where I can give advice and practical lessons about using media to reach out, that will improve communication with the rest of the world.

They are building an unofficial school for refugee children to ensure they receive an active life and education.

It's coming to the end of my second week in Greece now and I am aware that after coming this far, I still haven't seen the Moria refugee camp itself.

The organisation I held a workshop for told me they couldn't allow me access to the camp as I wasn't an official long-term volunteer.

The heat of the day would see the people at the camp gather under makeshift shelters

But I must see it.

As if by magic I am introduced to Fatma who is a 20-something refugee from Iraq who is offering her skills as a translator to other refugees.

Fatma has a car and a dog so we strike a deal that if I look after the dog (I am NOT a dog person) while she's in the camp she'll drive me to the outskirts of Moria and then it's up to me to get in. Deal.

An hour later I'm in the passenger seat of a tiny hot box of a car (it's 40 degrees by now) with Fatma at the wheel (who's driving skills are worse than mine) and her screaming abuse at other crazy drivers.

There's a Syrian family in the back who are also getting a lift to the area and there's a dog on heat sat behind me. I seriously couldn't make this up.

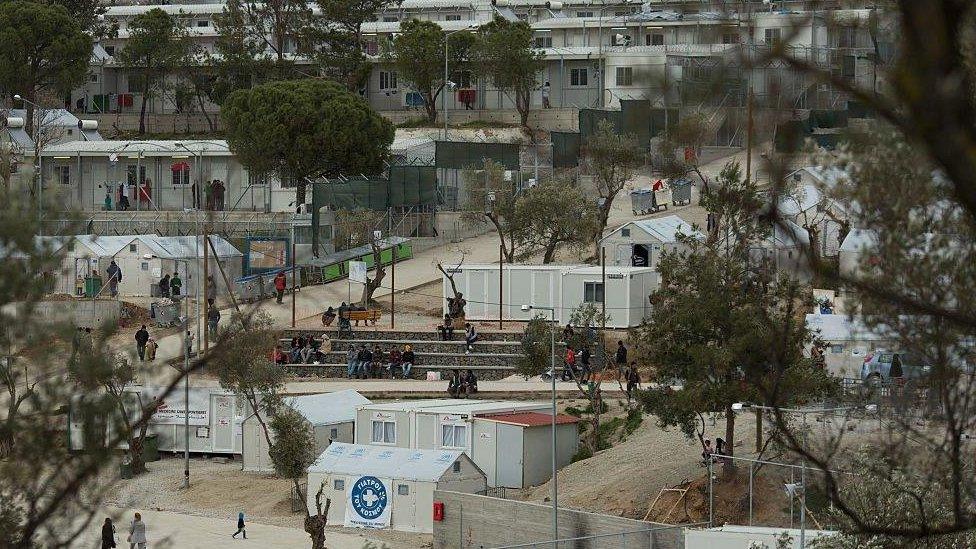

And then we arrive at Moria. People had told me that it looks like what they would imagine to be a 21st century concentration camp and I can see why.

Moria Refugee Camp on Greek island of Lesbos

With its steel structures, high fences, security check points and barbed wire surrounding the whole place it really is a scary and uncomfortable sight.

There are people inside who have done nothing wrong, they just want a better life, but here it seems they are prisoners and they have no idea where their futures lie.

The outskirts of Moria is surrounded by small tents with vans offering food and drink inside.

Being a former DJ and a lover of all music, I am drawn to the one where I can hear reggae music.

Portable shops were set up outside the camp by the aid agencies for people at the camp to buy supplies

Inside that tent there's a group of male asylum seekers gathered around a stereo sipping cans of warm beer.

They were all quiet around that table and didn't seem to understand each other's languages (there are many different forms of Arabic for example). The fear in their eyes was unmistakable and to be honest, if I'd been through what they've experienced I'd want a beer too.

As we communicated through the international language of music a good-looking guy struts confidently into the tent and everyone starts shouting 'Ali! 'Ali!'. Ali is the superstar of the camp.

A refugee himself, he speaks four different languages including various forms of Arabic, English and French.

He's the man who can speak their language and seems to be able to defuse any arguments in minutes.

He asks what I'm doing here and I explain that I'm a journalist from the UK but not here as a journalist, more as a human being that's taken time out from work to understand what's going on in the world I live in.

I explain that I can't get access to inside the camp and he tells me that I could walk to the check point to see if the security guards will let me in.

And they do. And suddenly I'm inside Moria.

It's huge inside there with hundreds of containers that house the asylum seekers while they wait to see if they can be moved to the local town or the mainland. Large tents are in place for people to sit in the shade during the incredible heat that pounds on the camp.

As well as the portable shops outside the camp, makeshift cafes have also been set up

Hundreds of people are lined up by a gated office with barbed wire sprawling across the top to see if they have been granted asylum or not.

In the centre, there are offices which house the lawyers and the doctors and the whole camp is segregated with men on one side and women and children on the other.

The lawyers, doctors and volunteers, of which there are very few between around the 2,200 asylum seekers that live in the camp, are inundated with thousands of cases and the work they do there for either very little money or as volunteers is absolutely astounding.

A ruckus breaks out between a young man and one of the lawyers. He has a young woman by his side and seems really distressed, shouting in Arabic waving documents he has in his hands in the air. Ali steps in to calm things down and later I ask him what the problem was.

Ali explains that the man and woman are married under the law back in Syria, but his wife has two months to go before her 18th birthday and here she is a minor and is therefore separated from her husband.

The documents in his hand were the certificates of marriage but in this country, they mean nothing.

Women make phone calls inside the Moria refugee camp

Along with all the thousands of cases for asylum the lawyers, staff and volunteers must deal with, there are also culture and legal differences such as this that must be dealt with too.

Since returning home from Greece, it turns out Moria has been set on fire because of a protest for the fifth time since the camp was established.

With over 2,200 people inside from different countries, cultures and backgrounds battling to get their cases seen coupled with massive language barriers, relentless heat and very little help available, it is inevitable that protests will happen and eventually get out of hand. Thankfully no one was injured in this blaze and the living quarters remain intact.

I've been back in Cardiff for almost three weeks and I speak to Zena and other friends I made out there every day.

If they have a communication problem with various authorities I try and help them by calling or emailing whoever it is to try and iron out the issues because for now, I speak better English than they do.

I'm trying to get to know refugees in my country and to actually take an interest in the Iraqi family down the road.

In this uncertain world that we live in anything could happen at any time.

What if you and I ever find ourselves in a situation where we need to flee the country in a desperate attempt to protect ourselves and our loved ones and we were told at almost every border that there is no help available and to dust ourselves down and walk another 1,000km to see if a neighbouring country has a different attitude?

What if one day we are in our lovely homes getting up from our beautiful comfy sofas ready to get into our king size beds for a good night's sleep and the next we find ourselves in a gated, barbed wired camp with no money and no prospects?

All I know from this experience is that we are all - each and every one of us - in this together.

- Published19 April 2017

- Published12 July 2017

- Published11 January 2017

- Published4 March 2016