Greece's refugee children learn the hard way

- Published

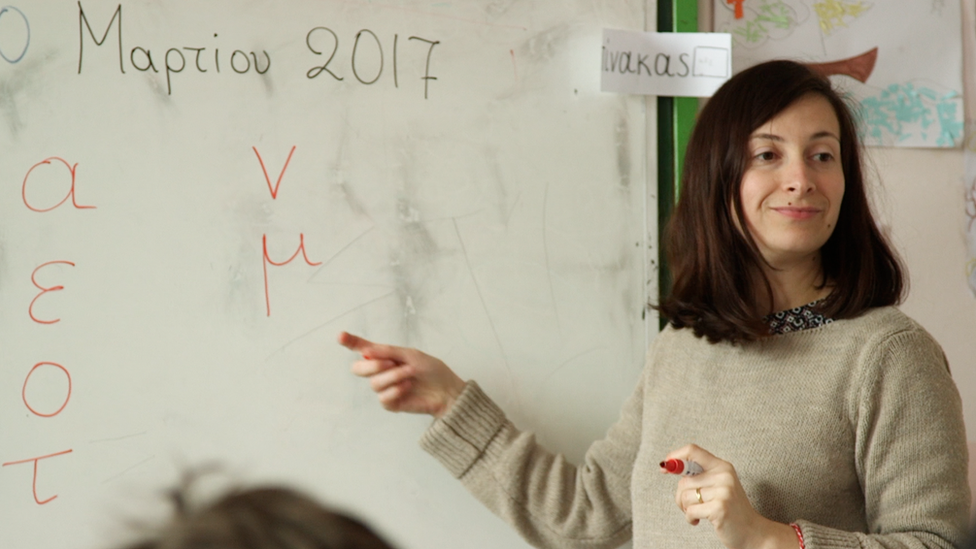

Refugee children attend school in Greece

The first day of school. It was supposed to be an exciting, happy time for so many of the 2,500 refugee children now living in camps in Greece.

But instead some were met with stone-throwing and nationalist slogans, after far-right demonstrators took issue with the government's policy to integrate them.

Fortunately for 10-year-old Moustafa, his appointed school in Thessaloniki saw no protests. And despite living in a metal container known as an isobox, the past few months have brought a form of structure to his life.

He spent a year fleeing war and fearing for his life, but now he has a schedule.

Every afternoon he boards a coach organised by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) that takes him to the city centre for school. He is one of 60,000 refugees and migrants trapped in Greece since relocation to European countries stagnated and the borders were closed.

Nationalists protested as refugee children started school in Oraiokastro, near Thessaloniki, in February

Moustafa explains how his village near Damascus was trapped between rival warring groups and, before it was too late, his family headed for Europe.

He recounts the moment they were rescued from a sinking dinghy - so accurately, it is as if he is playing back recorded footage.

He shows off the school kit he has been given, including notebooks, pens, pencils and a rucksack.

"The most important thing now is for me to study and learn Greek," Moustafa says. "I want to be a doctor."

Hostile reception

The new school initiative backed by the EU follows a law passed by the Greek parliament last August. It kickstarted new classes to prepare refugee children for eventual integration into the Greek education system.

Ninety-seven schools are currently involved. In three, the initiative was met with contempt. Crowds of far-right nationalists gathered to wave Greek flags, boo the children and shout slogans such as "My homeland won't fall!"

In the town of Profitis, riot police were called in to escort pupils after stones were thrown.

Nationalists demanded that Greeks should come first, not refugees

In Oraiokastro, protesters chained themselves to the school gates. The self-styled "Patriotic Union of Greek Citizens of Oraiokastro" said they didn't believe the pupils had been adequately vaccinated - something the health ministry has denied. In Perama, there were reports of physical violence.

In contrast, the arrival of pupils at Moustafa's school in Thessaloniki went smoothly. The headteacher, Ioannis Nomikoudis, says it is down to the communication between the government, school and parents' committee.

"The parents of the children here are not racist, but they do still have concerns and we cannot ignore that. The thing is, we didn't make the children's arrival debatable - like in some places."

For Education Ministry General Secretary Giannis Pantis, the fact that there were protests at only three of the 97 schools was a success. "In many other schools the children were welcomed with songs and balloons," he said.

He oversaw the programme from the start, when a scientific committee of leading Greek intercultural education experts and sociologists was brought together to provide advice. They assessed the work of NGOs in the camps and designed the curriculum of maths, Greek, English, art, IT and physical education.

Integration into the school system is an important part of establishing a new home

Lost in translation

The implementation of the programme has not come without its problems, though.

The lack of certified Greek-Arabic translators is a huge issue. The government says it is not a question of not being able to afford them, but that they just do not exist.

Refugee children are taught Greek - but lessons can be hard because few Greeks speak Arabic

Maths teacher Irene Voutskoglou said she did not realise how big the challenge would be.

"We can't really communicate well at all," she says. "I have to appoint a student as an 'assistant teacher' to help me. I didn't even realise that numbers were different in Arabic. Our zero is a dot in Arabic for example. And our five looks like a seven in Arabic."

Most translators are provided through charities, who receive funding from the European Union. But camp coordinators say the translators' language skills are often not good enough and that they are also needed to teach the children their native language.

Scarred by war

"This is supposed to be a transitional year," says Giannis Pantis, the man from the ministry.

"The children attend school in the afternoon, when the school day for current pupils has finished. We believe they cannot yet be fully integrated.

"Last week a child saw a helicopter and ran out of the school. Another started to cry and hid beneath the table. Some of these children, due to the war, are almost 10 years old but have never been to school. They can't read or write. Many of them have post-traumatic stress disorder. We have a lot to do this year."

Greek schoolchildren quickly made their refugee classmates feel at home

With a flagging economy and an education system already crippled by six years of austerity, the refugee crisis has further stretched Greece's capacity.

The government is reliant on just €7m (£6m; $7.5m) of European funding for the next two years (NGOs have received €83m directly) and the Greek national budget to implement the programme.

Despite the struggles, Mr Pantis says they are determined to honour the government's commitment to the fundamental and universal right to education.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.