World War One soldier Percy's love letters reveal last months

- Published

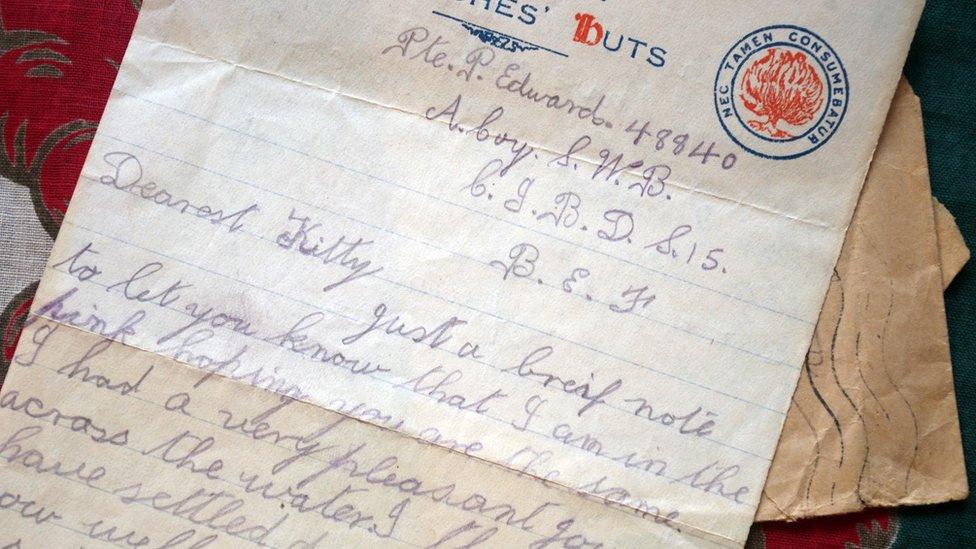

"I am in the pink...I had a very pleasant journey across the waters," wrote Percy

"It will be a long while before we meet again," wrote Pte Percy Edwards in a love letter to his girlfriend back home in Wrexham as he prepared to go to war.

But the pit worker, who had been called to serve in World War One, died on 28 September 1918 three weeks after arriving on the frontline in France.

His forgotten letters were rediscovered in London in a box of old postcards.

The centenary of his death is being marked in his home town with a talk by a historian who researched his life.

Percy, from Cefn Mawr, was "called up" and assigned to South Wales Borderers soon after his 18th birthday.

And he began his training in Liverpool from where he wrote regularly to Kitty Tombleson, a "domestic servant" from Froncysyllte, a stone's throw from his own family home.

In July 1918, during his army training, a letter described how he and comrades were being taught to use their bayonets against the enemy.

"The man who can pull the ugliest face and do the most shouting is the best, so you can think what sort of a thing it is," he wrote.

Fallen soldiers remembered

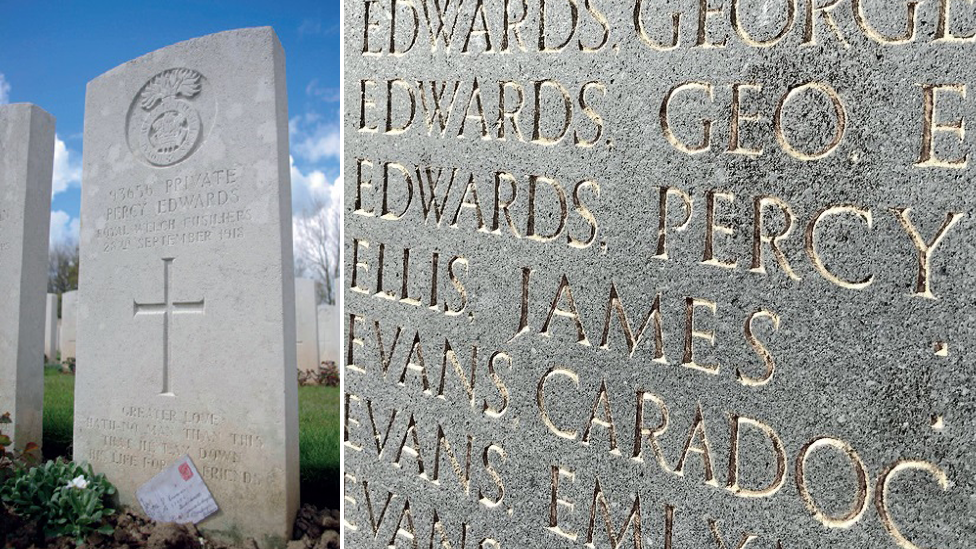

Percy's grave is in France and his name is on a war memorial at his family home in Cefn Mawr

School children in Cefn Mawr have spent the last 12 months researching the names of 130 local men, including Percy's, which are inscribed on their community's cenotaph.

And Percy's own letters have helped to paint a picture of that time after being included in a book by military historian and author Prof Peter Doyle.

He explained how an associate bought a box of old picture postcards at an auction only to find the bundle of letters.

Using them, local newspaper cuttings and war records, Prof Doyle, based at London South Bank University, has been able to tell his story in a new book Percy, A Story of 1918.

He is also sharing Percy's experiences with school children at Cefn Mawr Library on the centenary of Percy's death as well as giving a talk to the local historical society at George Edwards Hall.

In another letter, Percy revealed how some men became ill after being vaccinated against Typhoid, external fever, a bacterial infection that can spread throughout the body, affecting organs, ahead of being deployed overseas.

"The chaps are fainting when they are on parade, but they don't get much sympathy here," he wrote.

"Some chaps' arms have swollen so much that you can't see the shape of their elbows."

In late July 1918, Percy wrote: "I had a very pleasant journey across the water. I think we have settled down for a while now. Well, I hope so anyhow."

He was referring to his Channel crossing and his journey on to the Western Front in France.

"I think it will be a long while before we meet again, but I hope it will come very soon," he later wrote.

But by August, after being transferred to the 17th Royal Welsh Fusiliers, he was getting closer to the action.

"Dear Kitty, I have been up the line, and have now come back to the base for a rest."

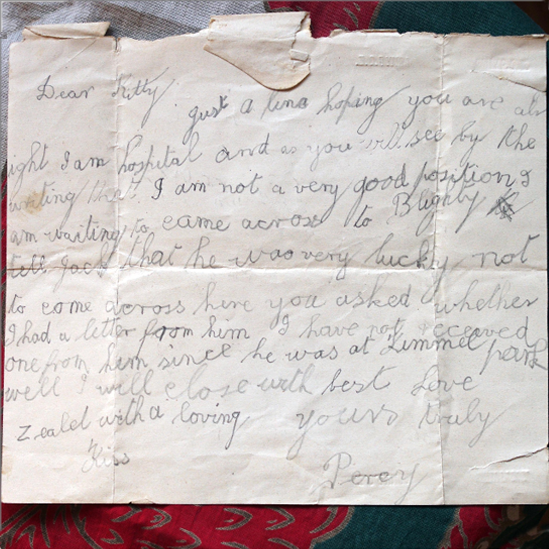

Percy's last letter: "I am not in a very good position. I am waiting to come across to Blighty"

In early September, he wrote: "I have had no time to write because we have been after old Fritz, who's been retiring ever since we went into the line.

"We followed him up for about six miles and he kept running away all the time.

"Fritz caught a few of our chaps with his artillery, and our artillery knocked many of his out," he wrote on 10 September 1918.

In this attack, two officers and 30 other soldiers were either killed or wounded, said Prof Doyle after checking the war records.

It was the same archives which explained that Percy had been mortally wounded after the Royal Welch Fusiliers came under artillery fire while at the Somme.

Percy was transferred to a hospital in Boulogne from where he wrote a final letter to Kitty: "Just a line hoping you are all right. I am in hospital and, as you will see by the writing, that I am not in a very good position. I am waiting to come across to Blighty."

Kitty had thought Percy was "safe in hospital" and, among the correspondence, Prof Doyle said he could sense she was "full of hope".

But her own letter addressed to Percy was eventually returned. It has the words "deceased" written on the front and the hospital address scribbled out.

Return to sender: Kitty's letter to Percy appears to have arrived at the hospital after his death

Prof Doyle and a researcher spent about four years researching Percy's story.

They found a local newspaper report in which the chaplain who attended Percy's hospital bedside described him as "true to the good principles in which he has been brought up".

They also found copies of the telegrams sent to Percy's family about his injury and then, three days later, his death.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records his grave, external at a cemetery at Terlincthun, near Boulogne.

Cefn Mawr community councillor Phil Vaughan, who has been organising the school history project, said Percy's letters and the new book helped to give children more details about the men whose names are on the cenotaph.

"We do need to remember them," he said.

So far, 15 descendants of the 130 men who are named on the cenotaph have been traced.

But no surviving family members connected with Percy Edwards have been found.

- Published28 July 2018

- Published26 September 2017

- Published14 February 2017