Murder memorials: A grisly history written in stone

- Published

The tragic tale of Margaret Williams is hinted at on the stone which condemns her murderer

Wandering around the picturesque cemetery at St Catwg's church in Cadoxton, Neath, a first-time visitor might be startled out of their gentle stroll by the stark message on top of one tall, weathered stone - MURDER.

This memorial in south Wales is one of a handful of "murder stones" erected around the UK, the majority over a period of about 100 years, to commemorate violent deaths that shocked the local communities.

The Cadoxton stone is dated 1823, and recounts the death of Margaret Williams, 26, who was from Carmarthenshire but was working "in service in this parish" and was found dead "with marks of violence on her person in a ditch on the march below this churchyard".

Miss Williams' story, such as is known from contemporary reports, tells of an unmarried young woman who had been working for a local farmer in Neath when she became pregnant.

The peaceful graveyeard of St Catwg's in Neath hides a harrowing tale in its midst

She had declared the father of the child was the farmer's son, and when her apparently strangled body was discovered head down in a watery inlet in marshes near the town, he was the prime suspect.

But whatever local opinion may have believed, there was no evidence to tie him or anyone else to the crime, and her murder remained unsolved.

However, the murderer was left in no doubt as to the feelings of the local community after this stone, part gravestone and part warning, was erected over poor Margaret's body.

Giving the details of her fate and the date of her death, the stone, erected by a local Quaker, continues: "Although the savage murderer escaped for a season the detection of man yet God hath set his mark upon him either for time or eternity, and the cry of blood will assuredly pursue him to certain and terrible righteous judgement."

This unsolved killing is unusual in the history of the surviving murder stones in that the murderer escaped justice. Most of the other memorials are to people whose killers were quickly detected, sentenced and dispatched via the gallows.

Dr Jan Bondeson, a retired senior lecturer at Cardiff University and a consultant physician, has made a study of the history of crime alongside his medical career and has written a number of books on the subject.

He became interested in murder stones after editing a book which featured them.

He said: "The murder stone in Cadoxton is the only one in Wales. There are plenty of them in England.

"There was an instinct for the local people to erect them. There was a strong instinct to commemorate a tragic murder."

Dr Bondeson has documented several further murder stones across the English counties, and one early example of the type in Scotland.

One murder stone has been immortalised by no less a writer than Charles Dickens himself. In the novel Nicholas Nickleby, the eponymous hero walks through the ominously named Devil's Punch Bowl at Hindhead in Surrey.

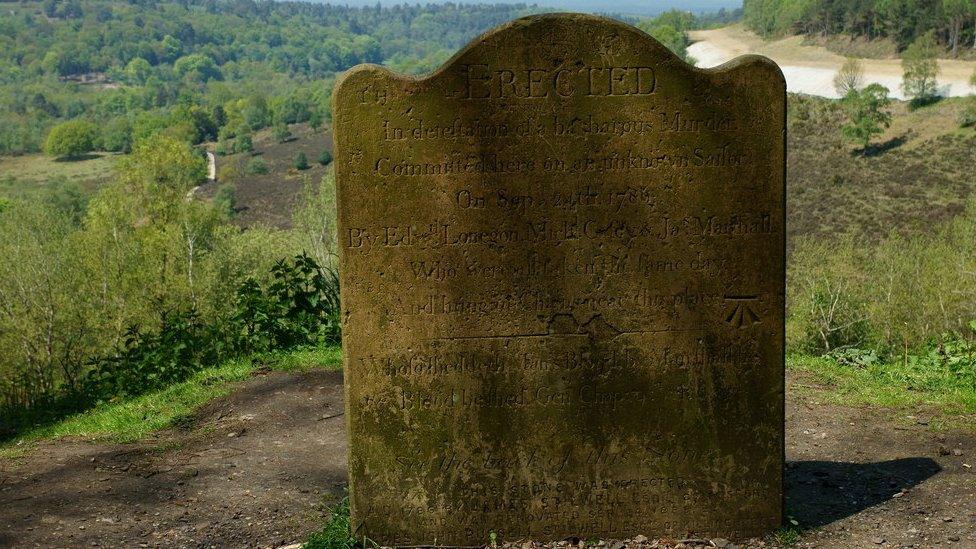

The murder stone at the Devil's Punchbowl, Surrey, features in Charles Dickens' Nicholas Nickleby

There, he and his companion come across the real-life stone marking the 1786 murder of a man known only as the Unknown Sailor.

The unnamed man was en route to his ship in Portsmouth when he visited a local pub in Thursley. There he fell in with three fellow sailors, and paid for their drinks and food before leaving with them.

The sailor was repaid for his generosity in the following way: They "nearly severed his head from his body, stripped him quite naked and threw him into a valley".

The three did not get far. The sailor's body was found soon after, and James Marshall, Michael Casey and Edward Lonegon were chased and captured after trying to sell the dead man's clothes at a pub.

They were hanged from a triple gibbet near the murder scene, and the unknown man was buried in Thursley with a stone paid for by local people.

But the local mill owner, James Stillwell, went a step further. He placed a stone in Devil's Punch Bowl itself, with this grim warning to future generations:

"ERECTED, In detestation of a barbarous Murder, Committed here on an unknown Sailor, On Sep, 24th 1786, By Edwd. Lonegon, Mich. Casey & Jas. Marshall

"Who were all taken the same day, And hung in Chains near this place, Whoso sheddeth Man's Blood by Man shall his, Blood be shed. Gen Chap 9 Ver 6"

Dr Bondeson said the majority of the stones appeared around the 1820s, adding "That was the high level for the erecting of murder stones. All of them are in the country - none are in urban areas."

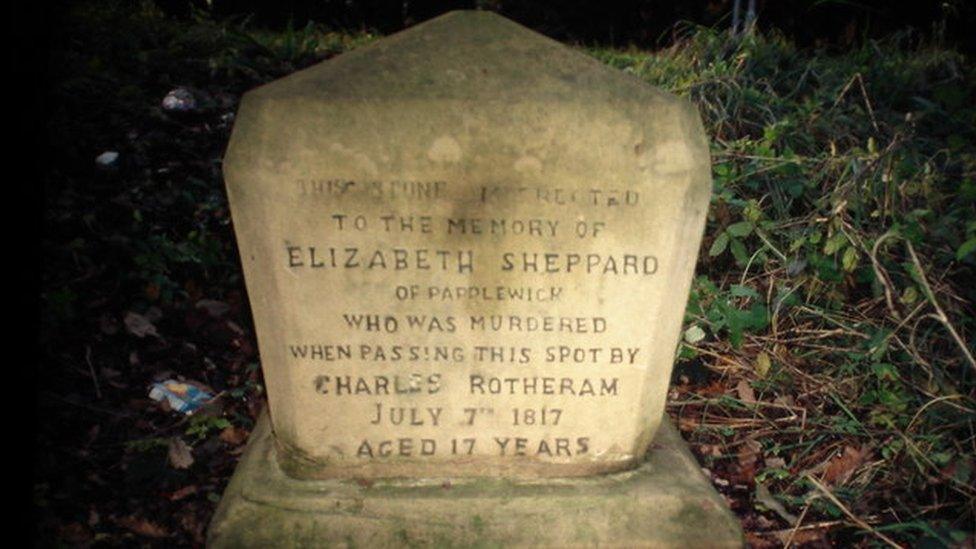

Bessie Sheppard was murdered on her way home after going to look for work

Elizabeth - Bessie - Sheppard was just 17 when she set out from her home in Papplewick, Nottingham, on 7 July 1817, to seek work as a servant in Mansfield, seven miles away. She found a job, but she never found her way back home, because on her return journey, a travelling knife grinder found her.

Charles Rotherham, a man in his early 30s, had served as a soldier in the Napoleonic wars for 12 years before beginning this new stage in his life.

He was seen on the road coming from Mansfield after drinking several pints where his path crossed Bessie's.

Her severely battered body was found in a ditch by quarrymen the next day. Her shoes and distinctive yellow umbrella were missing and there was evidence her attacker had tried to remove her dress but had failed.

Rotherham had sold Bessie's shoes and was on his way to Loughborough when he was arrested. He confessed to the crime and was returned to the scene where he showed a constable the hedge stake he had used to kill Bessie.

Like all murderers at the time, Rotherham swung for his crime. Local people, outraged by the attack, banded together to raise money for a stone to commemorate Bessie, which was placed on the site where she was attacked.

Bessie's stone simply honours the memory of the dead girl, but another stone erected to a female victim of violence has more of a moral tone, seemingly warning women against certain behaviour as much as expressing anger with the killer.

"As a warning to Female Virtue, and a humble Monument to Female Chastity: this Stone marks the Grave of MARY ASHFORD, who, in the twentieth year of her age, having incautiously repaired to a scene of amusement, without proper protection, was brutally violated and murdered on the 27th of May, 1817."

The story behind Mary Ashford's death and its aftermath is one which left a permanent mark on English legal history.

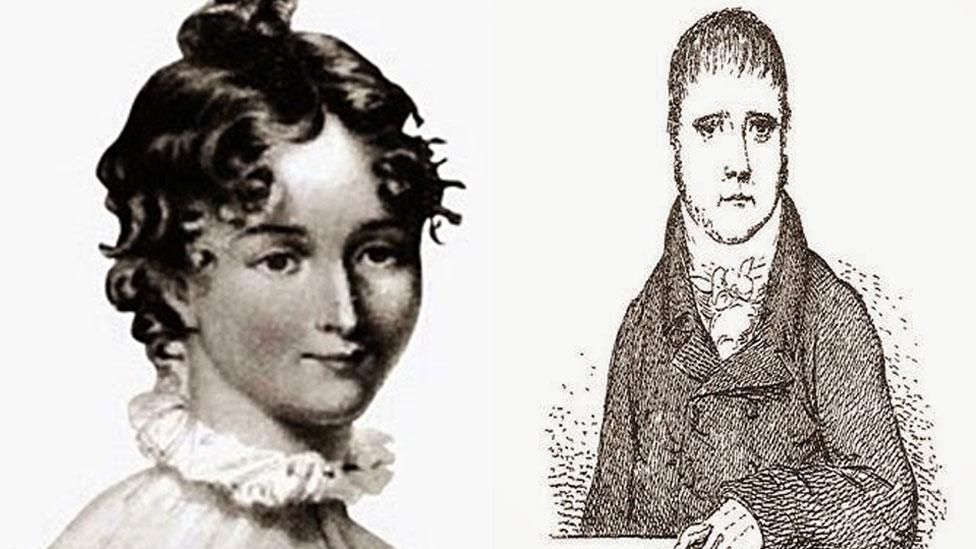

Mary Ashford and the man accused of her murder, Abraham Thornton

She had gone to a dance in Erdington, Birmingham, with her friend Hannah Cox, whom she planned to stay with overnight before returning to her place of work at her uncle's house in a neighbouring village.

At the dance, she met a local landowner's son, Abraham Thornton, and later reports confirmed the pair spent most of the night dancing together and having fun.

When they left the dance, Mary told her friend she would spend the night at her grandparents' home - possibly a ploy to spend more time with Thornton - and Mary and he went off together.

Mary returned to Hannah's house at 4am, changed her dancing clothes for her working clothes, collected some parcels and set out for her uncle's home.

About two hours later a labourer found a bundle of clothing and parcels on the path leading to Mary's home. The alarm was raised and her body was found submerged in a water-filled pit.

An autopsy showed she had drowned and had been raped shortly before her death.

You may also like:

People believed Thornton, having been rebuffed by Mary during their hours together, had lain in wait for her to return home and raped her before throwing her into the pit to drown.

He was duly arrested and tried, but a number of witnesses placed him at another location at the time of Mary's death and he was acquitted.

But the story does not end there. Mary's brother William Ashford began a private prosecution under an obscure ancient law, which allowed relatives of murder victims to bring an "appeal of murder" following an acquittal.

Thornton had a surprise up his sleeve though. In response, he demanded a trial by combat as was his right under that law, under which he could legally have killed Ashford, or if he defeated him, gone free.

Ashford was much smaller than Thornton, and declined the battle. Thornton was a free man, and the case was swiftly followed by a change in the law in 1819, banning such appeals and therefore trial by battle.

This murder stone at Disley in Cheshire commemorating William Wood was erected 50 years after the crime

Other victims include:

William Wood, of Eyam, Derbyshire, murdered by three men who robbed him of £100 in 1823 - his head was "beaten in the most dreadful manner possible". Two men were caught, one escaped justice. A permanent memorial was erected over 50 years after the crime after earlier versions were destroyed or removed, which showed the strength of feeling still present in the community about the murder.

Father and son William and Thomas Bradbury, who were brutally attacked in William's pub The Cherry Arms, known as Bill O'Jacks locally, on 2 April 1832 in Greenfield, Saddleworth. Their unsolved killings were recorded on a stone which noted their "dreadfully bruised and lacerated bodies".

The Marshall family - the "special horror", as noted in The Spectator at the time, of the Denham murders in Buckinghamshire, where a family of seven including three young girls were beaten to death at their home attached to their father's blacksmith's premises. The youngest, Gertrude, four, was found still clutched in her grandmother Mary Marshall's arms. Killer John Jones was found a few days after the killings on 22 May 1870 and speedily tried and executed. They are buried in one grave in St Mary's Church, Denham, where the original worn murder stone has been supplemented by a modern plaque to remember the victims.

The last word goes to those who chose to commemorate Nicholas Carter, a 55-year-old farmer from Bedale, Yorkshire, killed by a farm labourer as he rode home from market.

The stone laid at the murder site in Akebar - later to become a Grade II listed monument which hit the headlines earlier this year when it was badly broken in a car crash - had a very simple message, along with the date of his death, May 19, 1826.

Do No Murder.

- Published14 October 2010

- Published13 January 2015

- Published20 January 2011

- Published4 August 2012