World War One: Whitchurch Hospital provided solace from shell shock

- Published

The Welsh Metropolitan War Hospital's lodge and entrance

It was the condition that left World War One troops blind, deaf, mute and paralysed after the trauma of the trenches.

But soldiers were able to find some solace from shell shock at Whitchurch Hospital in Cardiff when they returned.

By the end of the war, tens of thousands of men were suffering from the condition initially thought to be caused by nerve damage after hearing the cacophony of the shells.

Dr Edwin Goodall was famed for his pioneering work as the medical superintendent of the hospital, which was known as the Welsh Metropolitan War Hospital during the war and run by the military.

Dr Goodall, who was appointed in 1906, opted for a more therapeutic approach than the other "quite brutal" treatments offered, explains historian Dr Ian Beech, a lecturer in nursing at Swansea University.

"For example, if a soldier was mute because of shell shock, then they would apply electric shocks to his jaw," Dr Beech said of the other techniques.

"Once the soldier shouted out, they considered that he was no longer mute."

Opening of Whitchurch Hospital on 15 April 1908. Left to right: Dr Edwin Goodall, Alderman Jacobs and William Brace, MP for South Glamorganshire

Nurses from The Welsh Metropolitan War Hospital in 1918

Dr Goodall was influenced by the work of Silas Weir Mitchell, who proposed that diet and rest could help treat nervous problems.

Alongside these changes, he used massages to relax patients and prevent muscle wastage.

Due to his emphasis on massage, prior to the war, all the nurses in Whitchurch had been trained as masseurs.

Despite the treatments being more humane, Dr Beech does not believe that the more caring treatment was due to Dr Goodall's kind nature - he says that he simply realised that harsher treatments were "unproductive in terms of a therapeutic approach".

Dr Goodall was also forward-thinking in his management of nurses - he insisted that civilian nurses treated the patients, despite the hospital coming under military control.

After the war he ensured that female nurses continued to nurse male mental health patients, something which was unusual at the time.

A postcard from William Dean, a soldier of the Welsh Regiment, who was admitted to the hospital in November 1917

Dr Beech, who wrote his PhD on Whitchurch Hospital, explained: "He believed that the nursing of male patients by males was less therapeutic insofar as it was less relaxing, less caring.

"At the end of the war he insisted that this carried on when it returned to civilian use, much to the annoyance of the local trade unions, who were pushing for jobs to be kept open for men returning from the war."

Therapeutic techniques showed a move towards treatments similar to those for returning soldiers today, who can suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

However, Dr Beech is clear that shell shock is different to PTSD: "They've got the same cause but they haven't got the same manifestation.

"That may be because society's changed, the way in which people respond to trauma has changed."

He added that the pressure of warfare during WW1 meant people had to be physically ill to mean they could not work.

"The only real way the psyche could deal with that was shut down and become ill, because if you were ill you couldn't be expected to charge the guns, and you couldn't be blamed for not charging the guns," he said.

"So shell shock in the First World War had a very physical manifestation."

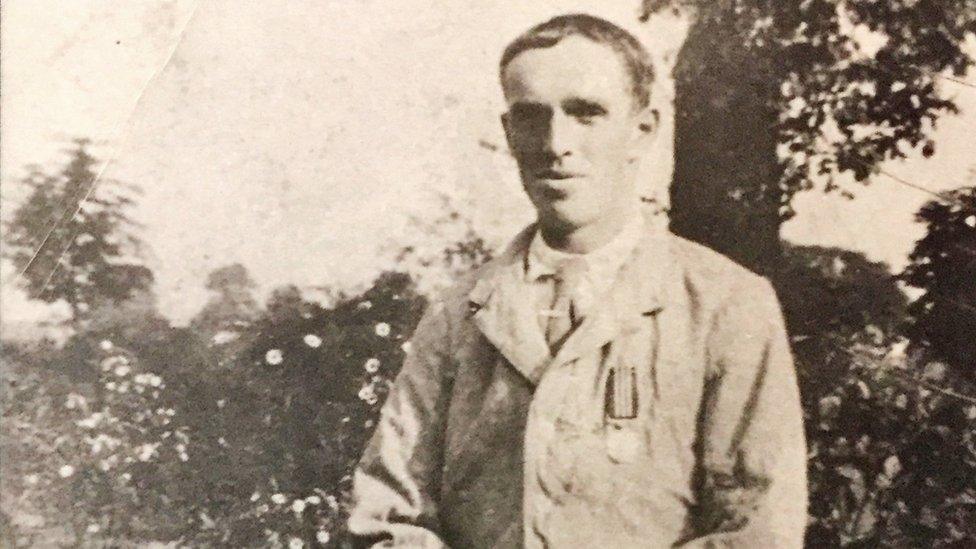

Horatio Ellis Evans, who was treated at the hospital

Although the treatment for shell shock would be considered barbaric in today's medicine, Dr Beech said the doctors of the time were simply doing their best with the information they had - and it is too easy to judge through hindsight.

"We know different things now that they didn't know then," he added.

"If we were to walk onto the docks of Southampton today, with a ticket in our hand for America, and we saw this big ship with Titanic written on the side of it, we wouldn't get on."

Anyone who knows of soldiers treated at Whitchurch Hospital during WW1 is asked to contact Whitchurch Hospital Historical Society.

The Armistice 100 years on

Long read: The forgotten female soldier on the forgotten frontline

Video: War footage brought alive in colour

Interactive:, external What would you have done between 1914 and 1918?

Living history: Why 'indecent' Armistice Day parties ended

- Published11 July 2018

- Published18 March 2018