Gwynedd's slate landscape 'could give region new future'

- Published

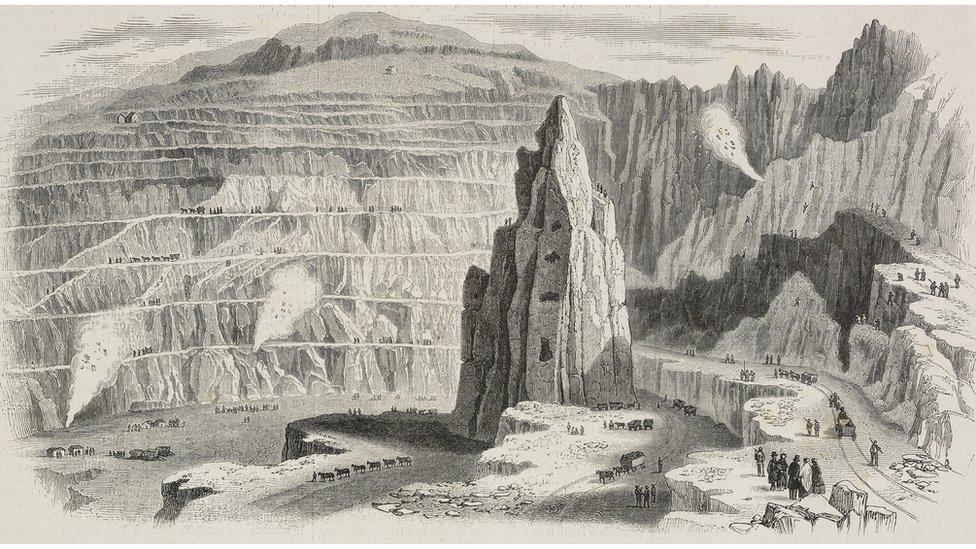

The slate quarry terraces dominate the landscape around Llanberis

It's an industry 500 million years in the making.

Last week it was announced the slate landscape around Gwynedd will be the UK's preferred nomination for Unesco World Heritage site status.

If accepted, it will see the "quarries which roofed the world" rank alongside icons such as the Grand Canyon and the Great Barrier Reef.

Dafydd Roberts, of The National Slate Museum, said securing the status would be a boost for the region's future.

"Of course we want to welcome tourists to celebrate the heritage of when slate was at its height in 19th Century, but we also want to send out the message it's still a living, breathing, vibrant industry today," he said.

"After the doldrums of the late 20th Century, north Wales slate is once again highly sought-after by architects. There's no better example than the brilliant array of slates used in the Senedd."

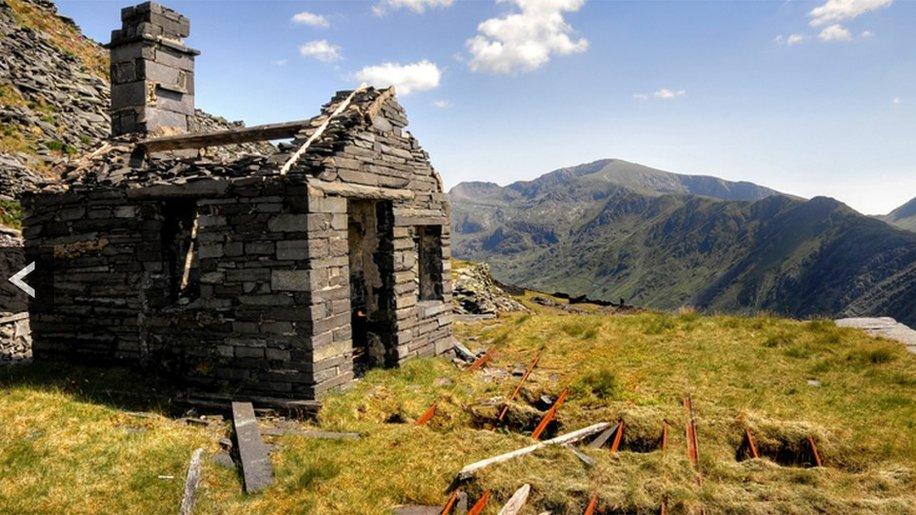

The ruins of the small Conglog Quarry near Blaenau Ffestiniog

Slate's incredible strength-to-weight ratio has been realised since Roman times, with the fort at Segontium, Caernarfon,, external roofed in the metamorphic rock from 77AD.

Quarrying remained on a small scale for a millennium and a half, with the Cilgwyn quarry thought to date from the 12th Century and the earliest records at Penrhyn coming in 1413.

You might also be interested in these stories:

Small teams of men would pay landowners a royalty to work the stone on their land.

However, when water, and latterly steam power began to make large-scale extraction profitable, owners grew interested in taking over themselves.

In 1760, 1,000 men produced 50,000 tons per year. Fast forward 120 years later, and 17,000 men were producing half a million tons, which were exported as far afield as Canada and Australia.

An illustration of Penrhyn Quarry, already a tourist attraction in 1851

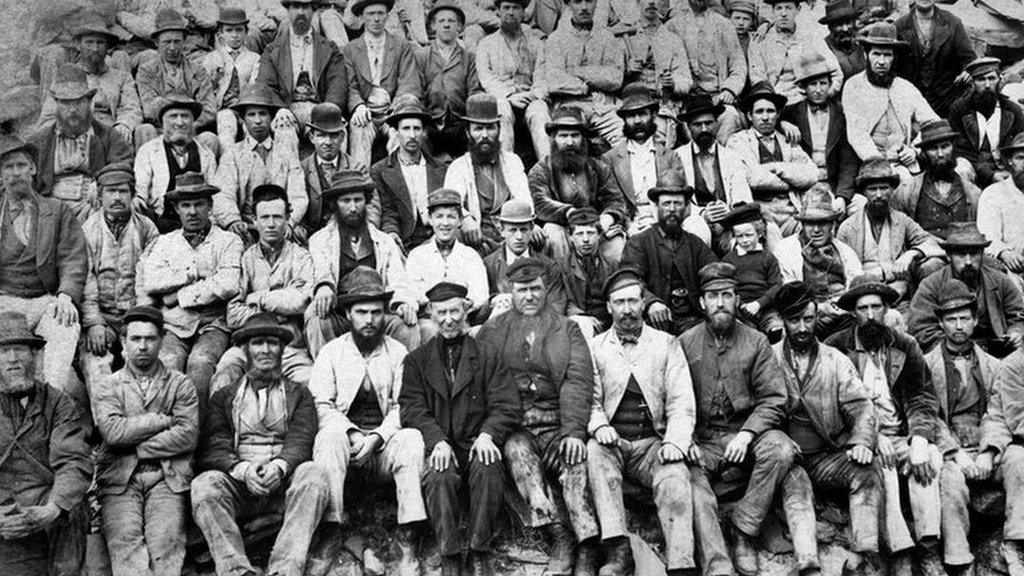

Slate workers at the Dorothea Quarry in the Nantlle Valley

At its peak, slate accounted for half of north Wales' income - and it even rivalled the scale of coal mining in the south.

Though as soon as they had arrived, the good times were about to peter out.

A slump in global prices drove down quarrymen's wages, leading to a series of bitter strikes and lock-outs.

The Penrhyn Quarry lock-out from 1900 to 1903 was the longest ever industrial dispute at the time.

You might also like these:

Mr Roberts believes the industry never truly recovered.

"Customers were forced to look elsewhere for slate, and once foreign imports had filled the gap, Welsh slate never regained the virtual monopoly it once enjoyed.

"The First World War also decimated the industry, but there was a simpler explanation, slate just went out of fashion.

"By the 1920s and '30s, towns had moved away from 'Coronation Street' rows of slate-roofed terraces to suburban semis with tiles."

'Slipping' home using the rail track

However, Mr Roberts said slate's arrested development did have an unintended consequence: preserving the area's distinct Welsh-speaking culture.

"Both coal in the south and slate in the north started out as bulwarks of the language and culture," he said.

"However, as coal continued to grow, it drew in workers from all over Britain and eventually the world, diluting the language.

"The same thing probably would have happened in north Wales, had it not been for slate faltering.

"Whilst the quarries brought in farm labourers from nearby areas, they never grew to the extent that they sucked in all-comers."

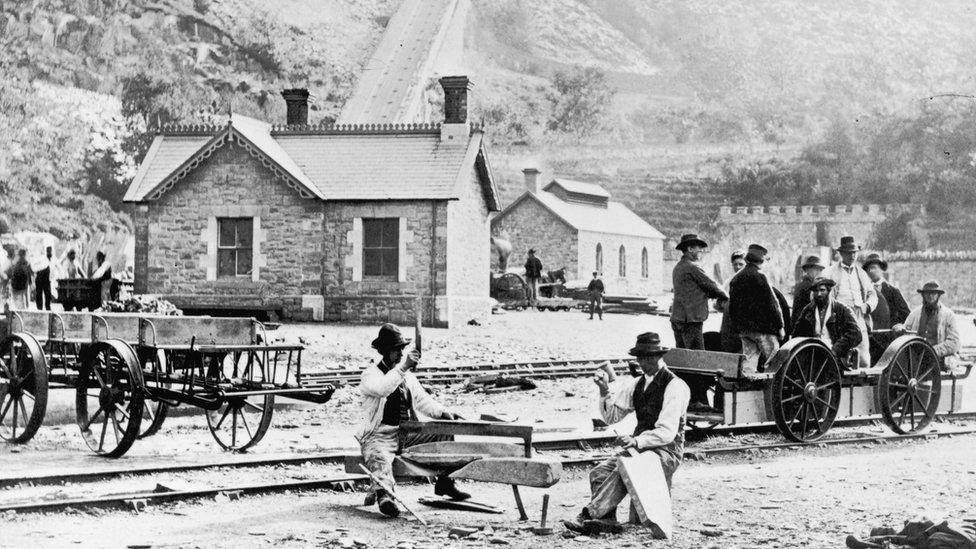

Quarrymen cutting slate and using a pedal-powered railway truck at Llanberis around 1880

It is that same culture and heritage which Mr Roberts is hoping will receive a boost from getting Unesco World Heritage status.

"I think all of us in Wales, wherever we are, are sometimes a little guilty of not fully appreciating what we have on our own doorsteps," he added.

"If we can look out of our windows and think to ourselves that the world ranks what we have here as important as the Taj Mahal, that's going to boost local confidence, help the economy, and encourage us to attract even more visitors."

- Published23 October 2018

- Published24 August 2018

- Published10 November 2017

- Published11 April 2013