Brexit uncertainty weighs on food sector in Wales

- Published

- comments

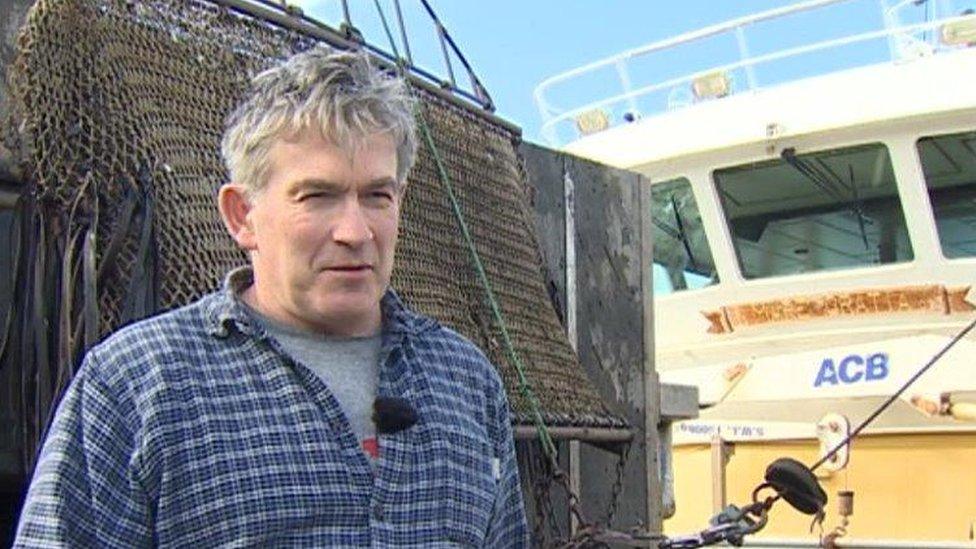

James Wilson's entire crop of mussels needs to go immediately to his customers in Holland and France

A mussel farmer who exports his entire haul to the EU is to stop work for six to eight months until there is more certainty around Brexit.

James Wilson, from Bangor in Gwynedd, ramped up production before the end of March and has saved enough money to last the summer.

A Cardiff university trade law expert said Brexit uncertainty was the biggest worry for food and farming businesses.

Dr Ludivine Petetin said small firms in particular were struggling to prepare.

Mr Wilson's boat brings 2,000 tonnes ashore each year from the Menai Strait.

Getting his mussels to market in France and Holland as quickly as possible is vital to make sure they do not go off. In colder months he has up to 36 hours, but in summer it is less than 18.

He fears delays and checks at the border will put him out of business. He decided to end his commitments to customers in Europe for the time being and has been preparing for the worst-case scenario.

"At least we have money in the bank so that no matter what happens we've got a cushion of income that helps pay our fixed costs."

Waiting to see if the UK leaves with or without a deal has been "confusing, stressful, disturbing, deflating and dismaying", he said.

Why are Welsh producers worried about a no-deal Brexit?

Silver lining?

The food sector was worth £6.8bn to the Welsh economy in 2018, employing 217,000 people.

Dr Petetin said even if Parliament approved a way forward in the coming week to avoid a no-deal Brexit, firms were still potentially facing years of uncertainty as long-term trade agreements are worked out.

But she said one silver lining under any Brexit scenario was a potential growth in sales of Welsh food and drink at home.

"This is something we should also focus on - what can we do, what can companies and businesses do to source more local food and make sure the local economy keeps growing."

BBC Wales spoke to others in the food and drink business about how the ongoing wrangling over Brexit was affecting them.

Stockpiling wine

Wine sellers are bulk buying over fears of hold ups at the borders, according to a Bridgend business

Daniel Lambert Wines, based in Pyle near Bridgend, is one of the UK's biggest importers of wine, supplying firms like Majestic, Waitrose and British Airways as well as over 250 independent retailers and restaurants.

Mr Lambert describes the prospect of leaving without a deal as a "nightmare".

He decided to stockpile, in case it became more complicated and time-consuming to get hold of European wine.

"Currently we have two and a half times the amount of stock we should normally need at this time of year," Mr Lambert explained.

The businesses they supply are also bulk-buying, so Brexit has actually boosted their sales by 40%.

"But the question is what's the hangover going to be after Brexit?"

The fruit and vegetable 'gap'

Fresh fruit and vegetables cannot be stockpiled and delays on imports could hit supplies, says Ben Pratt

Ben Pratt is director of Watson and Pratts organic fruit and vegetable wholesaler in Lampeter.

The UK is about to hit what he calls the "hungry gap" between the UK's winter and summer harvesting seasons.

At this time of year they mainly have to import, particularly from Spain and Italy which have a "jump start" on the season.

Tropical fruits such as mango and bananas always come from far flung destinations - but some products travel through other EU countries before arriving in the UK.

They have tried to plan for Brexit but it has been a challenge.

"The goal posts change... it's hard to find accurate information about what we should be doing... We're playing it day by day and hoping for the best, like most people," he said.

Under the UK government's proposed plans in the event of no deal, the vast majority of fresh fruit and vegetables will not incur any import tariffs, but the firm is concerned about the cost of red tape.

"Brexit, once it's sorted, is totally fine. It's not daunting at all, but it's that moment of crashing out. We're a very 'just-in-time' kind of operation because we're selling a product that has a very short shelf life," he added.

"The panic is how much cash we as a business have in reserve to stand produce disappearing, produce rotting on trucks... We can stand a couple of weeks, but can we stand two months of disruption? I wouldn't have thought so."

Curry costs

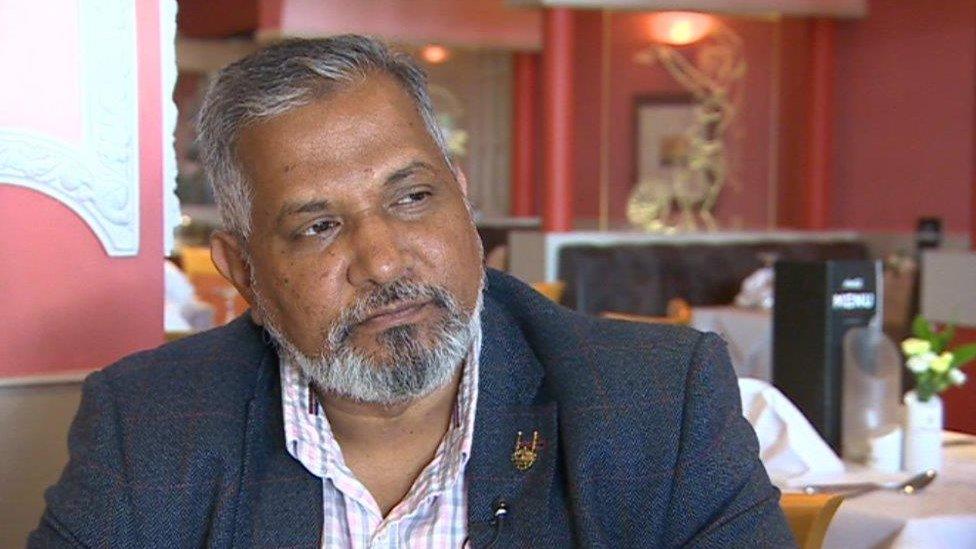

The owner of the Juboraj chain of restaurants is concerned about the potential for rising costs

Ana Miah is the managing director of the Juboraj group of restaurants in Cardiff. He said their overheads have been going up for four to five years, but more so over the last two to three years, since the referendum.

He said the value of the pound had increased the cost of food products from abroad and he is concerned about the impact of "no deal" on the economy generally.

"We have definitely seen a downturn in the amount of time people are eating out. If disposable income is not there you tend to cut out on the luxuries and eating out is a luxury."

- Published2 April 2019

- Published21 August 2018

- Published13 February 2018

- Published6 June 2018