Wales' Jewish history: Call to record it before it is too late

- Published

'Giving a face to the faceless'

Volunteers are trying to record the 250-year history of Jews in south Wales before it is too late, they say.

A century ago, there were 6,000 Jewish people in Wales, with the figure now in the hundreds and many aged 80 or over.

The Jewish History Association of South Wales (JHASW) has crowdfunded £3,000 towards an archive.

"Of the 72 people we've interviewed since August 2017, seven of them have already died and the average age of the others is 85," said Klavdija Erzen.

"So it's vital we create a permanent record of their lives in Wales."

Ms Erzen, who is JHASW's project manager on the scheme, explained "time is of the essence".

A mobile exhibition of 72 oral histories and 6,000 images is currently touring Wales.

But volunteers want to create a more lasting legacy, which could cost £60,000 to place online and at museums.

It is hoped Heritage Lottery Fund money could help cover this and "train and coordinate volunteers to comb museums and libraries across Wales", according to Ms Erzen.

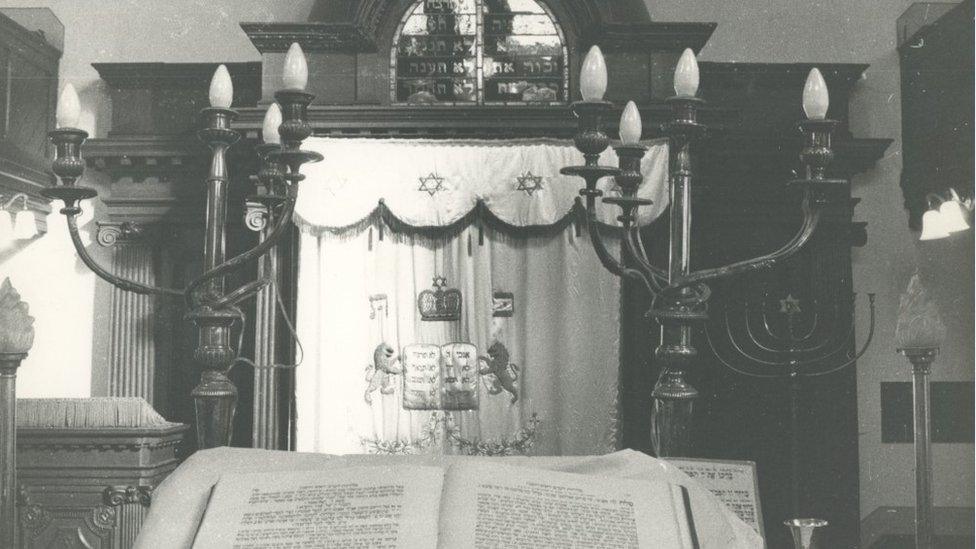

The interior of Merthyr Tydfil's synagogue which was open from 1877 to 1982

He explained that finding records and accounts of Jewish people could be difficult because they generally "aren't filed as such".

South Wales' first Jewish community was established in Swansea in the 18th Century, with a plot of land allocated for a Jewish cemetery in 1768.

The Industrial Revolution attracted workers from Russia and other areas of eastern Europe.

By the late 19th Century there were also thriving communities in Merthyr Tydfil, Brynmawr, Aberdare and Pontypridd.

In the 1940s, so many Jewish workers had flocked to support the war effort that the predominant languages heard on Treforest Industrial Estate, Rhondda Cynon Taff, were Polish, German and Czech.

Jewish businesses in Pontypridd became so successful that the town's high street was colloquially known as "Jewish Street".

Yet by 1999, Merthyr Tydfil's once 400-strong community had disappeared altogether when George Black, known as "The Last Jew in Merthyr", died aged 82.

Pontypridd's synagogue was open from 1895 to 1978, and is now a block of flats

Ms Erzen said the reasons for the decline are complicated.

"Partly it's a success story," she said. "The first-generation immigrants worked as labourers and hawkers, but they wanted their children to move into the professions, for which they had to move away.

"Also, in common with many other groups, the decline of heavy industry in south Wales forced Jewish people to look elsewhere for work."

This created a "snowball effect", where more and more people moved away, leading to the closure of synagogues and community services.

Ms Erzen added: "Today there are no Jewish schools or kosher facilities like butchers and delicatessens in Wales.

"Food has to be delivered from London every fortnight."

The Wartski family ran a shop on Bangor high street - the history of Jews in north Wales has been documented with a walking trail by Bangor University

If the grant is successful, it is hoped Bangor University researchers will help create a walking trail around Cardiff - similar to one in north Wales.

There are also plans to research names of Holocaust victims listed on a tablet at the Cardiff Reform Synagogue.

"We have managed to collect memories from non-Jewish people too, telling us what the communities and businesses meant to them," Ms Erzen added.

"It would be easy to dwell on the stories of anti-Semitism, but I think that would overlook the many hundreds of positive experiences, and the immense Jewish contribution to Welsh culture, sport, enterprise and life in general."

The JHASW mobile exhibition is touring Wales, external until the end of September.

- Published16 December 2017

- Published17 March 2019