Why do Welsh place names appear around the world?

- Published

Llandudno in South Africa was named after the Welsh town because the headlands on the bay appeared similar to early settlers

Why does Swansea pop up on the map several times in the USA and Australia? How did magnificent Milford Sound in New Zealand come to bear the name of Milford Haven in Pembrokeshire? And what is the story behind Llandudno in Cape Town, South Africa, external?

The answer, according to Swansea University's Gethin Matthews, is fairly complicated but relates to how Welsh skills in heavy industries were highly sought after.

"It's all about economics - Irish emigration was much more about desperation, while Welsh emigration was driven by aspiration," he said.

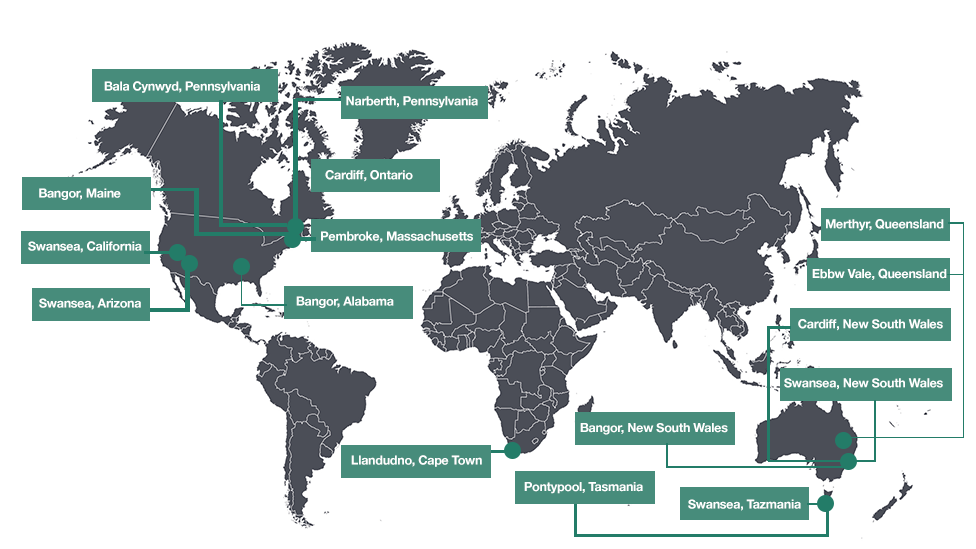

This map shows just a few of the Welsh place names around the world

The story involves a Welshman who played a major role in extending the American Civil War and a Swansea businessman who built a copper smelting plant in the Arizonan desert.

Dr Matthews said the biggest wave of Welsh emigration came in the late 19th Century.

Scranton, Wilkes-Barre and Pittsburgh, all in Pennsylvania, had the biggest Welsh populations before 1900, Dr Matthews said.

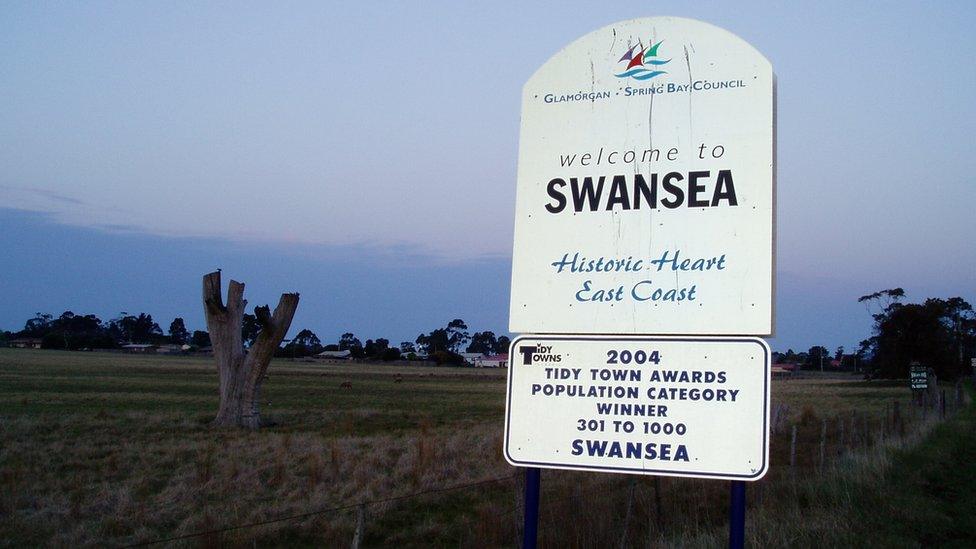

Swansea appears across the USA and Australia, including here in Tasmania

Many of these places were likely given their names during the first wave of religious migrants between 1682 and 1700.

But the figures are sketchy. For example, estimates of the number of Welsh people who emigrated to the United States between 1820 and 1950 range from 90,000 to 300,000.

Most of these lived in Pennsylvania and Ohio, with relatively smaller numbers spread across New York, Illinois, Wisconsin and Iowa.

There is a Neath in New South Wales, Australia

From the 1850s onwards, emigrants were able to cross the Atlantic on steam ships within two weeks, although the trip to Australia would have been far more unpleasant.

In Australia, Dr Matthews said many of the "obvious" examples of Welsh place names were in New South Wales or Tasmania, which have towns called Neath and Swansea.

But bearing the name of a Welsh town or city was not necessarily a good indicator of the level of Welsh immigration, he added.

Were they successful?

George Mitchell was born in Swansea and established a copper smelting plant in Arizona, USA

Swansea-born George Mitchell emigrated to the USA in 1888 and established a massive copper smelting plant in Arizona. The new town would be named after his birthplace.

"Unfortunately he didn't think through that you need more coal than copper ore," Dr Matthews explained.

"He had lots of copper ore but it cost more to build a rail road to get coal there and he blew a fortune."

Welsh expertise was highly sought after in two particular fields: coal and iron.

Prof Anne Knowles, external, who teaches at the University of Maine, has written about Welsh agricultural and industrial migration to the USA.

She taught at Aberystwyth University in the 1990s and has descendents from Llanbrynmair, in the county now known as Powys.

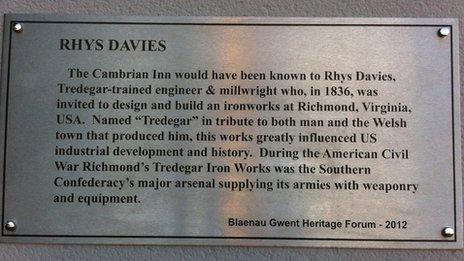

Designed by a Welshman, the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia, was vital to the Confederate South in the American Civil War

"Welsh iron workers could demand a premium in wages," Prof Knowles explained.

Rhys Davies, from Tredegar, was "very skilled" and "knew how to build a first-class iron works". He left south Wales in 1833 to help build an ironworks in Richmond, Virginia.

The works he designed and helped build - named the Tredegar Ironworks - extended the American Civil War by giving the Confederate South a huge arsenal.

'Organised labour'

Prof Knowles said Welsh workers also introduced the idea of organised labour and class identity.

But this brought them into conflict with owners and managers, who liked their expertise but not their assertiveness.

"People who owned the iron works - Americans - quite clearly didn't want to put up with 'uppity' workers. Welsh workers were more independent and went on strike."

The Welsh workers also refused to work with slaves.

"Slaves were much more reliable, and it was clear to the workers that if they trained the slaves, they would be training their replacement.

"There was no feeling of anti-slavery. I certainly found no evidence of that - they were as racist as the rest."

Many agricultural workers left the land-scarce area of Mynydd Bach in mid Wales to seek a better life in Ohio and Pennsylvania

Many of the agricultural emigrants came from an area called Mynydd Bach in what is now central Ceredigion.

Land was scarce for farmers in mid Wales and the lure of the abundance of America was strong.

One farmer who gave into temptation was a man from Pontrhydfendigaid called Richard Jones, who kept sheep on a farm called Bronberllan.

"That is what he named his farm in Wisconsin," said Prof Knowles.

His farm in Wisconsin was 200 acres (81 hectares) compared with 20 acres in Wales, according to Prof Knowles.

"He was known as King Jones because he was wealthy and had the biggest house around," she added.

Signs of Welsh immigration appear in US towns and villages, such as the Welsh Congregational Church in Oak Hill, Ohio

Emotional attachment

While Prof Knowles was living in Madison, Wisconsin, she was taught Welsh by a woman called Eluned Evans, from Llanerfyl in Powys, who would later develop Alzheimer's disease.

"When I went to see her recently she seemed pretty out of touch," she explained.

"I started talking to her about Llenerfyl and Llanbrynmair, and she turned to me and said 'I know a girl from Llanbrynmair' and started reminiscing about her and how she taught her Welsh.

"It showed me in a very personal way the emotion attached to place names and why people named these new places they were coming to after their home in Wales."

- Published28 July 2015

- Published1 March 2015

- Published14 July 2013

- Published12 June 2012