What is climate change doing to Wales?

- Published

- comments

Aberystwyth seafront was hit by storms in 2014 - the local council is worried rising sea levels leave it vulnerable

One world problem, one corner of Wales - climate change is already "happening before our eyes," according to a man watching the coastline closely.

Aberystwyth is a seaside town which has already had experiences of extreme weather. Five years ago, properties were evacuated as waves crashed onto the promenade.

It seems as good a place as any to take a look at what impact climate change may be having on communities.

Its university is also the base for scientists who are researching the wider climate issues - and how we might adapt.

And travel along the nearby Dyfi estuary and you find some of Wales' most important nature reserves and wildlife, which are vulnerable.

"You can't put all the cost on county councils," says Councillor Alun Williams

Alun Williams, cabinet member for carbon management in Ceredigion, said rising sea levels were threatening its flood defences.

The local authority is trying to plan how to manage the effects of climate change along the coast.

Stood on the shingle ridge which acts as a barrier between land and sea at Tanybwlch beach near Aberystwyth, Mr Williams said: "The sea is overtopping this bank much more regularly than it used to - it's just a matter of time before it breaks through and moves inland."

Rising sea levels and more frequent storms mean there are fears this defence could soon be breached.

Sea levels are rising, leaving Wales's coastline vulnerable

It is an example of how global warming is already affecting Wales - the country's 1,680 mile-long (2,700km) coastline is on the frontline, leaving local authorities like Ceredigion with difficult decisions to make.

Mr Williams highlighted one area where the waves have carried an avalanche of pebbles down into the River Ystwyth on the other side of the ridge. Beyond that, farmland is slowly getting wetter and saltier.

The council hopes its research at this site, in partnership with Natural Resources Wales, will help inform its plans for managing the effects of climate change along the coast.

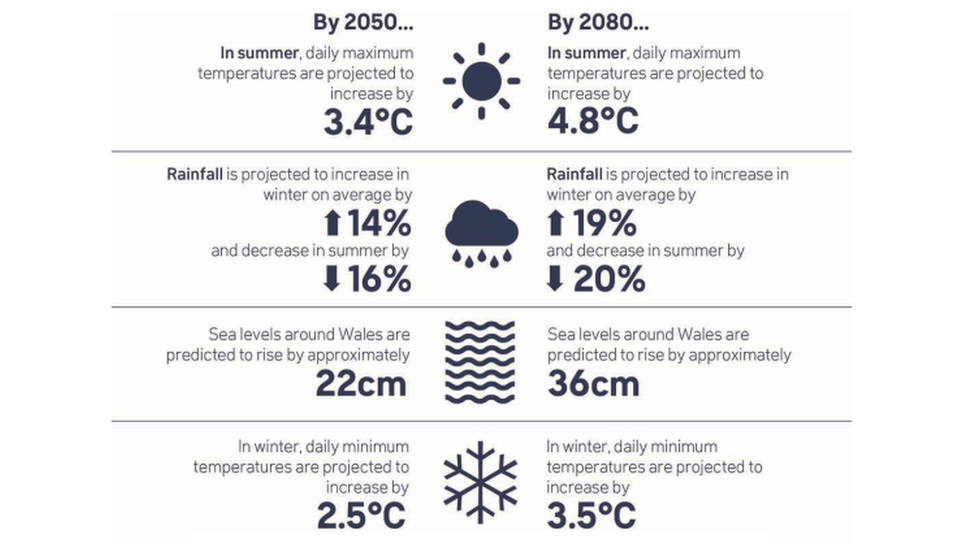

Projected impacts from climate change from a medium emissions scenario

No homes are threatened here, but the course of the river could change, affecting Aberystwyth harbour, and a long diversion to the Wales coastal path may also be needed.

Elsewhere, defending seaside towns and villages, roads and railways will prove costly.

"We need to manage this on a Wales-wide level - you can't put all the cost on county councils that happen to have long coastlines, we need a wider strategy," Mr Williams urged.

There are "more losers than winners" at RSPB's Ynyshir reserve in the Dyfi estuary

The changing climate is also showing signs of hitting Wales' wildlife and the habitats they rely on.

Some 13 miles (20km) from Tanybwlch, at the RSPB's Ynyshir reserve in the Dyfi estuary, site manager David Anning says his team are noticing changes "all around us".

They include new visitors such as little and great egrets, usually found in southern Europe.

"A lot of the wetlands around the Mediterranean are gradually drying out - so we'll probably be seeing more and more of this effect where formerly southern species are moving north," he said.

The golden plover has been a regular resident of the reserve, but is in decline

But overall he claimed there were more "losers than winners" for the reserve, with regular residents such as black grouse and golden plover in decline.

"We're losing a lot of the species which have been here for millennia, and that's really sad as many of them are globally quite restricted," he added.

The salt marsh habitats are under pressure, squeezed between the encroaching sea and existing flood defences.

David Anning is site manager at Ynyshir reserve, where they are allowing the sea to flood certain fields during high tides and storms

As a result the reserve has decided to remove sections of the mounds that have traditionally kept the sea out, allowing it to flood certain fields during high tides and storms, creating new marshland over time for the birds that want it.

The "headache" - as Mr Anning puts it - is what to do with species such as the lapwing - who prefer freshwater habitats.

"Increasingly we're going to have to look at managing wildlife on a much wider, landscape scale as climate change has a bigger and bigger effect."

Milder winters could mean some crops like oilseed rape will not get cold enough to trigger flowering, says Dr Fiona Corke at Aberystwyth University

Farmers face challenges too, with predictions Wales will face more rain, warmer temperatures and fiercer storms in future.

Dr Fiona Corke, from the National Plant Phenomics Centre at Aberystwyth University, works in a giant robotic laboratory, the only facility of its kind in the UK, where they are stress-testing different plants to see how they would fare as climate change takes hold.

Hundreds of pots are being watered automatically, some to the point of being waterlogged, others to simulate drought conditions.

"This is a barley trial - testing 250 varieties - but we've also done something comparable with oats, which is another very important crop in Wales," Dr Corke explained.

"Another issue is that as winters become milder, some crops like oilseed rape won't yield as well as they won't get [cold enough] to trigger flowering.

Fiona Corke is stress-testing different varieties of crop

"By understanding the requirements of different plants we can possibly start to adapt the crops we're using in Wales," she said.

A Welsh Government spokeswoman said it had published a series of proposals to "re-focus billions of pounds of investment towards tackling the climate and ecological emergency".

"Tackling climate change and species extinction are not issues which can be left to individuals or to the free market. They require collective action and the government has a central role in making collective action possible," she said.

- Published20 September 2019

- Published23 April 2019

- Published4 September 2019