South Africa's xenophobic attacks: Why migrants won't be deterred

- Published

Fear is growing that "gangster politics" is taking root in parts of South Africa, writes the BBC's Andrew Harding after visiting an area hit by an outbreak of attacks on foreigners, mostly from elsewhere in Africa.

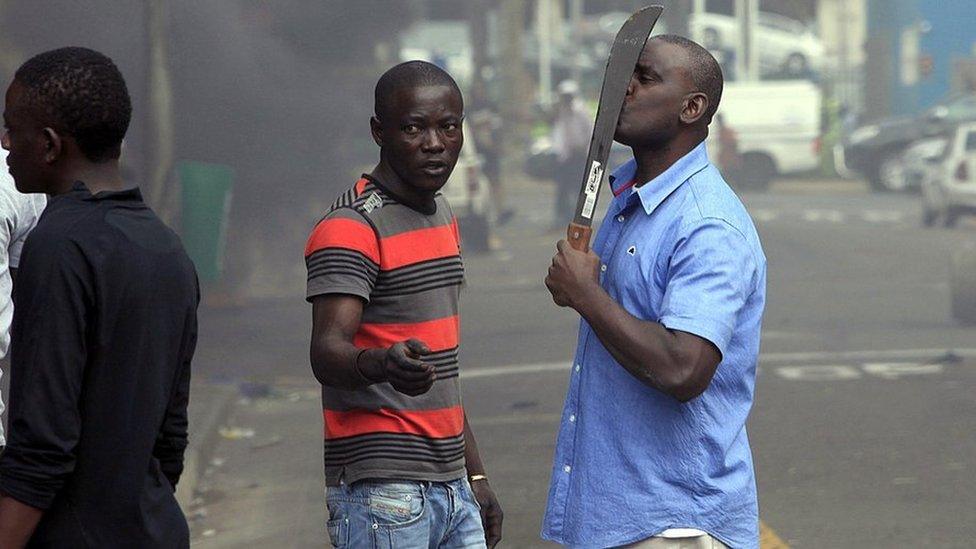

On the vast, rapidly urbanising plains east of South Africa's commercial capital Johannesburg, the sporadic but grotesque violence of recent weeks has now subsided, leaving behind a sense of confusion and guilt.

At the same time, there is a gloomy confidence that this will not be the last time that such scenes - of firebombed shops, burned cars, terrified foreigners, looted supermarkets and armed mobs - play out on the streets of poor, dysfunctional townships like Katlehong.

"It is a time bomb. A time bomb," said local community organiser Papi Papi, pointing across the road to a new informal settlement of perhaps 100 metal shacks crowded onto a small patch of wasteland.

"They caught him in his car and burned him alive," he said, referring to the death of a Zimbabwean man during the unrest.

"These places are packed with migrants, more than locals. The government is not planning, just reacting, even [when it comes to] basic infrastructure, so that is where the problem is," he explained.

Katlehong has been one of the flashpoints of the violence

A group of local men, playing a game of Ludo on a scrap of cardboard, at first insisted that opportunistic criminals were entirely to blame for the violence, but they soon began to complain about the presence of foreign nationals.

"I'm not xenophobic," insisted a man who gave his first name as Alfred. "But these foreigners are prepared to work for less."

"They work for small money," his friend Frederick agreed. "And they hire their own, so it's hard for us to compete. There is frustration."

'I'm scared'

South Africa's government has been quick to apologise for the latest spasm of xenophobic violence.

Although some politicians in the governing alliance have sought to blame the troubles on criminals and foreign governments, President Cyril Ramaphosa has led efforts to patch up the country's image on the continent and to protect its foreign investments.

Nigerians who returned home speak of the violence they encountered

But despite furious criticism from some African governments and nations, the larger truth is that South Africa - with its huge and highly developed economy - remains Africa's biggest magnet for migrants, and, while a few foreign nationals have decided to return home, the majority seem to have weighed up the risks and the rewards and chosen to stay.

"If I leave this job because I'm scared, there's no other job, no other option for me. There's nowhere for me to go," said a 23-year-old Ethiopian, from behind an elaborate security fence that covered the front of his small grocery shop in Katlehong.

'Protection rackets'

There are an estimated 3.6 million migrants in South Africa, out of an overall population of well over 50 million, according to a spokesperson for South Africa's national statistics body.

About 70% of foreigners come from neighbouring Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Lesotho.

As rapid urbanisation transforms Africa, the concern is that the pressures and tensions being experienced in growing cities in South Africa and elsewhere are likely to increase.

"If I were a mayor of a city in Africa today, I would be scared," said Loren Landau, an expert on migration at Wits University in Johannesburg.

"I would be scared because we don't have the resources or capacity to absorb the populations that are coming and all the projections show that cities - whether it's Lagos or Nairobi or Accra or Johannesburg - will continue to grow. No matter how much we invest in rural areas, they will grow, and the states and governments are not ready for them."

How Africa's population boom is changing our world

South Africa's International Relations Minister Naledi Pandor has spoken of the need to give people the education and skills to enable them to find jobs and not to "see themselves in competition with other groups that come to our country".

But the economy is not growing fast enough to tackle rising unemployment, which stands at nearly 30%, external, and many believe that xenophobia is, fundamentally, a political problem.

"This is about who governs the townships now and in the future," said Prof Landau.

"What we see is protection rackets replacing formal government - gangster politics. Whether they whip up xenophobic protests or… other violent protests, this is done by local politicians to bring attention and to boost their own political careers."

In Katlehong, the idea that politicians were exploiting the tensions to increase their profile and popularity found plenty of support.

"Everyone wants a piece of the cake, and it's a small cake. Politicians, migrants, everyone. The have-nots will always feel the brunt of everything. They say it's criminal but we can see it is political," said community organiser Papi Papi, who expressed concern that a forthcoming local election would trigger more violence.

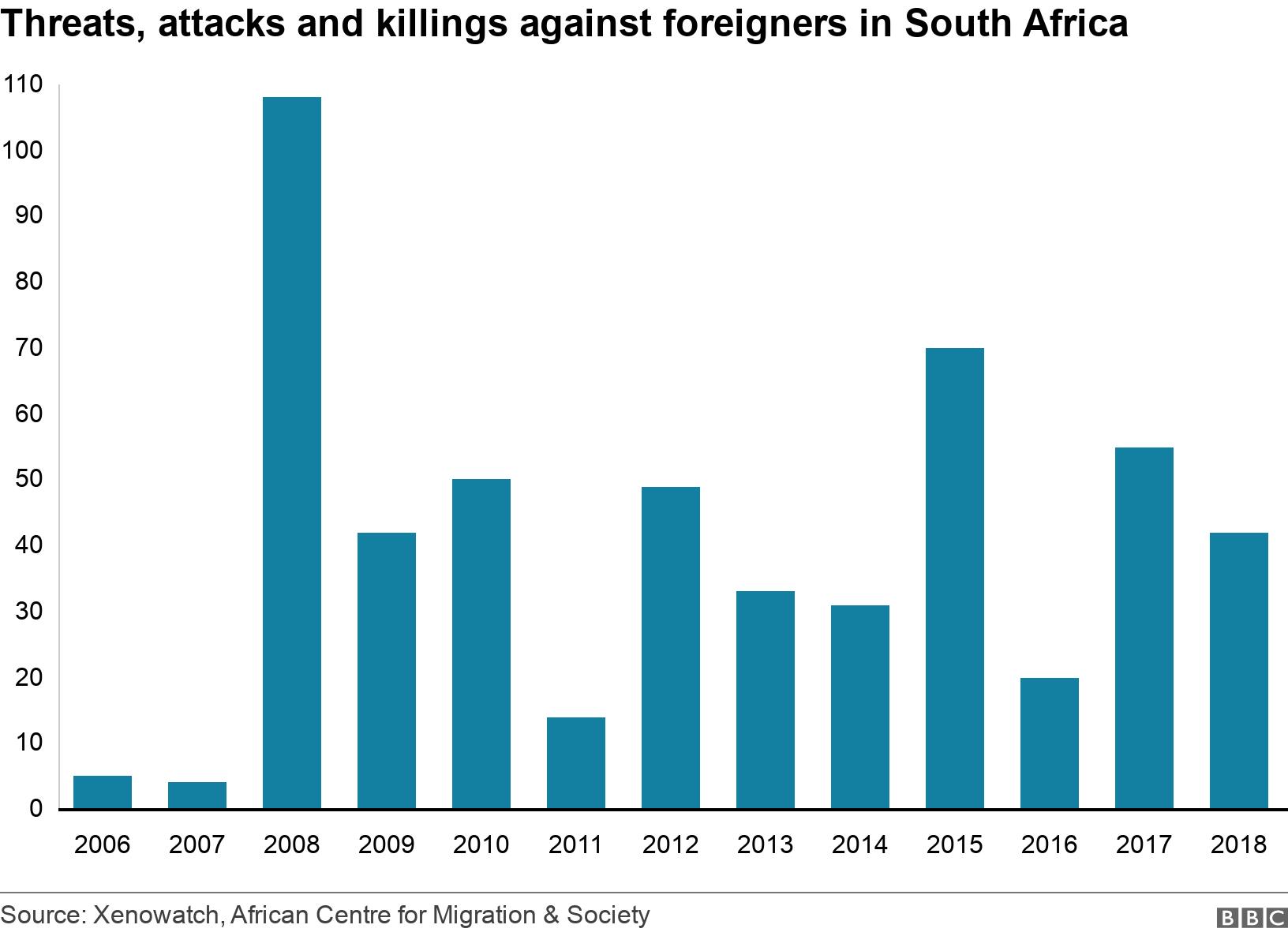

But it is worth noting that South Africa, like many other nations on the continent, has absorbed large numbers of immigrants with relatively little organised political opposition, compared to some European countries, and only sporadic violence.

And the recent turmoil has prompted many churches and civil society groups to encourage dialogue and to reinforce a message of tolerance.

- Published29 August 2019

- Published2 October 2019

- Published1 May 2014