Driving in Wales: Why the north-south road is so slow

- Published

- comments

Long, beautiful - but slow - this is the A470 lovingly captured by photographer Glenn Edwards

When we are watching Wales play - whether it's rugby or football - it is one nation united, supporting its teams.

But what about the real world physical connections that bind us - especially between the north and south?

For a small country, our sprawling, twisting road network makes it a very large place.

It can take longer to drive from Llandudno to Cardiff than it does to take your car across the Irish sea to Dublin.

Get stuck behind a timber lorry on the A470 - and you'll find it would have been quicker to drive to London instead.

But why? It's 190 miles - why should that journey take so long?

Here's one answer: Powys is the largest unitary authority in Wales - covering 2,000 sq miles.

If you want to drive through Wales from south to the north - then the A470 trunk road will take you through vast swathes of Powys.

It is arguably one of the most beautiful drives in the UK. But quick - it is not.

One reason is this: according to figures from StatsWales, external - it has precisely 7.1 miles of dual carriageway road.

That is in a county stretching from the border with Oswestry in north-west Shropshire - all the way down to Ystradgynlais in the Tawe Valley of south Wales.

Neighbouring Ceredigion fares even worse. It has just 0.4 miles of dual carriageway road.

Why so little dual carriageway?

It is all about history, politics and of course, cash.

It was not until the late 1700s that there was any attempt to address what was widely regarded as "appalling" roads in Wales, according to the late, great Welsh historian John Davies, in his book A History of Wales.

Driven by the coal and ironmasters of the industrial revolution in north east Wales, the first turnpike road company was formed in Flintshire in 1753 - road builders who then charged a toll to travel on their private highways.

Within 60 years, there were more than 200 turnpike schemes across Wales - many "crippled by corruption", according to Mr Davies.

In turn, it led to civil unrest - including the the Rebecca Riots, whose supporters dressed as women and smashed-up toll booths in protest.

It led to an act of Parliament in 1844 establishing Roads Boards for south Wales counties, leading to better roads in parts of the region than most of the rest of Britain.

But even then, it was not the roads that had priority - it was the railways. The railways followed the money - and the money was in coal and steel, from sea ports to seats of power - from west to east across south Wales and into England.

It also meant those established industrial corridors were already in place when rail finally gave way to road, and the rise of the car.

The route to Ireland

Holyhead remains the second busiest passenger port in the UK - its road links are vital

In north Wales, the road network also reflected the political priorities - and they established a route that is as almost as important today as it was in the 1800s.

In 1784, it would take 48 hours to reach Holyhead from London - the ferry port for Dublin and an Ireland still firmly under British rule.

The strategic importance meant some heavy investment by the government in a new road built by the engineer of the day, Thomas Telford.

By 1836, the journey from London by horse and coach was cut to 27 hours.

But it is a similar story - a route running east to west - from Wales to England.

In between - rural Wales, a rural population, and only local transport needs. Simply put, the need for a major road network linking the north and south of Wales did not exist - and was never built.

21st Century Wales

But what about modern Wales - where car is king? Does Wales now need that link - dual carriageways stretching from Llandudno to Cardiff?

No - according to one internationally respected expert.

"It's basically about traffic flow - there's not the demand to justify a dual carriageway," insists Nigel Smith, the University of Leeds engineer who has advised the Welsh Government on transport network management.

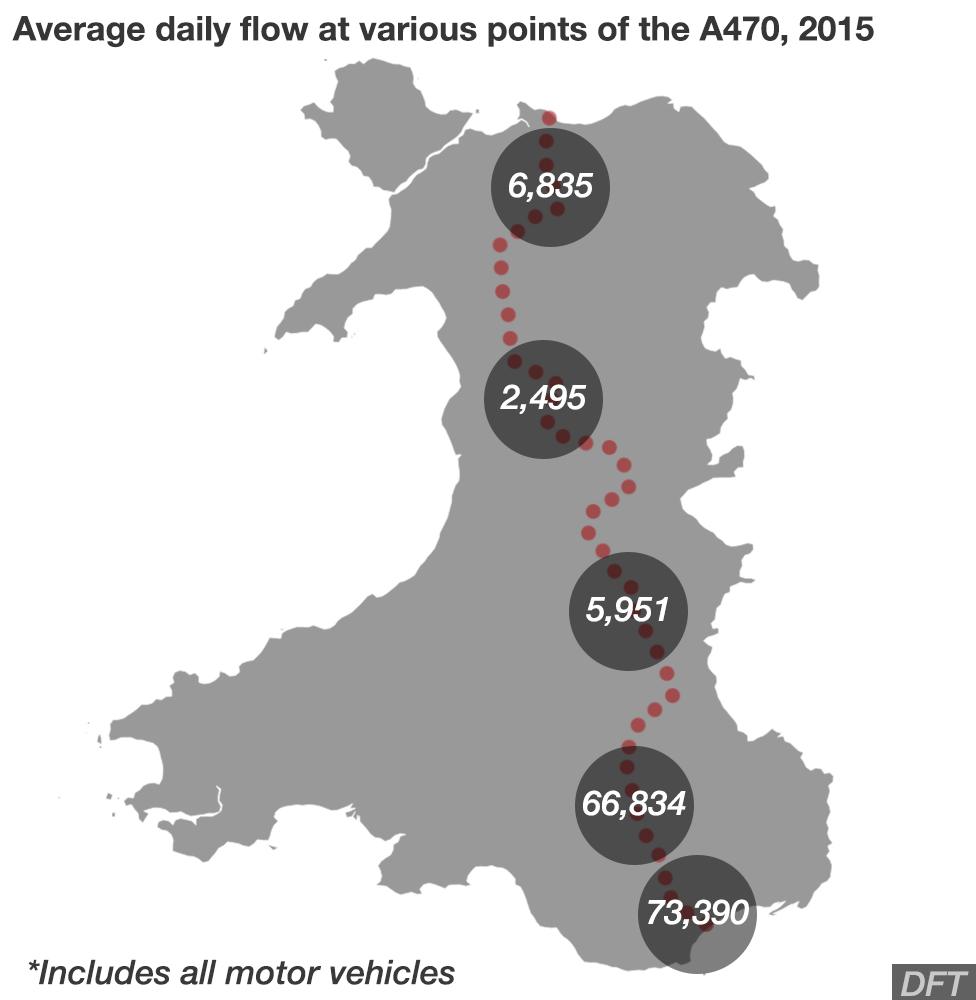

The number of people travelling on the A470 reduces significantly in the more isolated parts of Wales

But is that a chicken-and-egg problem he is describing? The traffic volume on routes such as the A470 is not there, because the public know how long it takes to traverse?

No again, insists the academic.

"If that was the case, we would still see bottlenecks on the routes - and that is not the case," he argues.

"The connection is just not there."

End of the road?

Could overtaking lanes dotted along the A470 help?

So is that the end of the matter? Will it always be a go-slow from Abertillery to Abergwyngregyn, from Barry to Bangor?

Not necessarily.

Back in 2017, as part of the Welsh Government budget deal with Plaid Cymru, some £15m was earmarked for improving north-south road routes.

The cash would be used to build stretches on the A487 and A470 for overtaking - so cars can actually get past the convoys of HGVs or caravans that can all too often bring traffic to a snail's pace.

According to the Welsh Government's National Transport Finance Plan, external, which was updated last year, there are 18 such schemes being considered on the north-south route to improve journey times.

In total, more than £70m is being ploughed into the mid Wales road networks between 2018 and 2020.

Schemes such as the A483 Newtown bypass in Powys have already been completed, while work on the £135m Bontnewydd bypass outside Caernarfon in Gwynedd is well underway.

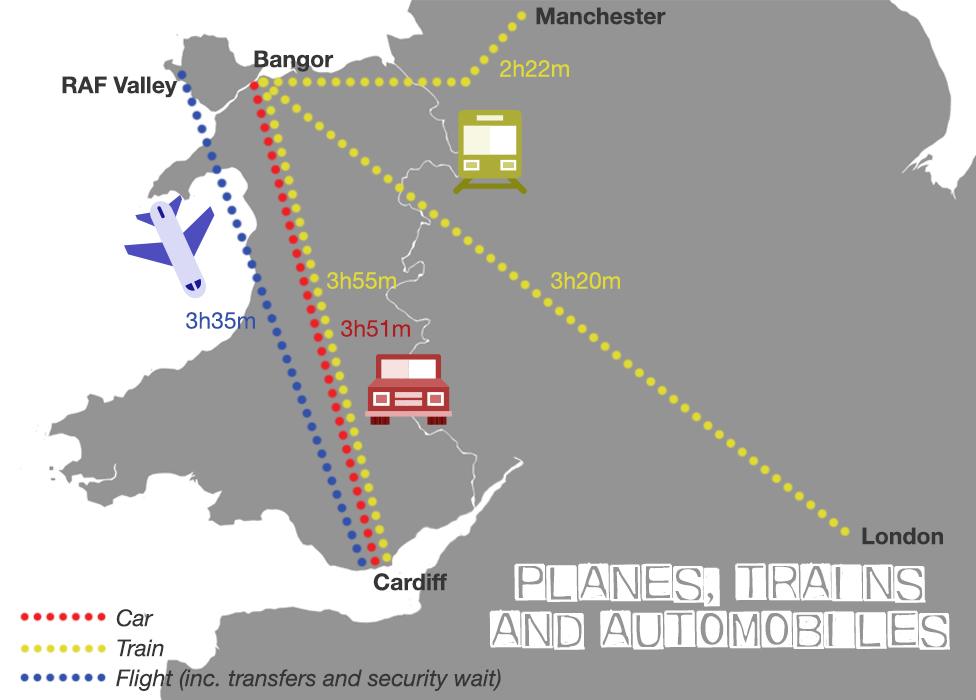

"Beyond road travel, we support the Cardiff to Anglesey air link as well as key north-south TrawsCymru bus services, and have identified improvements to the western corridor - from Ynys Môn to Swansea Bay - in our vision for a fully devolved Welsh railway," said one Welsh Government official.

"There are quite clearly significant geographical and topographical challenges to overcome - as well as financial ones - but we remain committed to improving connectivity between the north and south of Wales."

Parties united?

While some might argue that Wales remains divided, split by the road network that favours east-west routes to and from England, it does appear they are united by their calls for improvements.

Plaid Cymru says transport remains a "key driver of economic growth", the Welsh Liberal Democrats say "better links are needed" and the Conservatives believe road network improvements are needed "to enable local people and visitors to Wales to take advantage of what our country has to offer".

But another key message from them is that public transport - and especially rail - that should be the focus for the future, not roads.

Should we be moving from road to rail?

Plaid's leader Adam Price recently pushed for a "Crossrail-style" service for the south Wales valleys, between Pontypool and Treherbert.

The party has also - along with the Lib Dems - called for reverses to the Beeching rail cuts of the 1960s - especially in mid Wales.

"The best way to deliver better transport between north and south Wales and within mid Wales is to deliver more frequent and faster rail services," said Welsh Lib Dem peer Baroness Randerson.

Welsh Conservatives also appear to be singing from the same hymn book in Wales, calling for "rail and bus services fit for 21st Century Wales".

This year has already witnessed plans for an M4 motorway relief road shelved - and a "climate emergency" declared by the Welsh Government.

Perhaps the reality of the 21st Century is that the rise of the road is over - for now.

This story has been inspired by a question from Jez Morgan, who asked: "Why doesn't Wales have at least a dual carriageway linking north to south? Unusual in a modern country?"

- Published15 September 2016

- Published9 February 2018

- Published4 August 2019

- Published3 July 2018