Natural history: Bangor's part in the quagga's missing leg

- Published

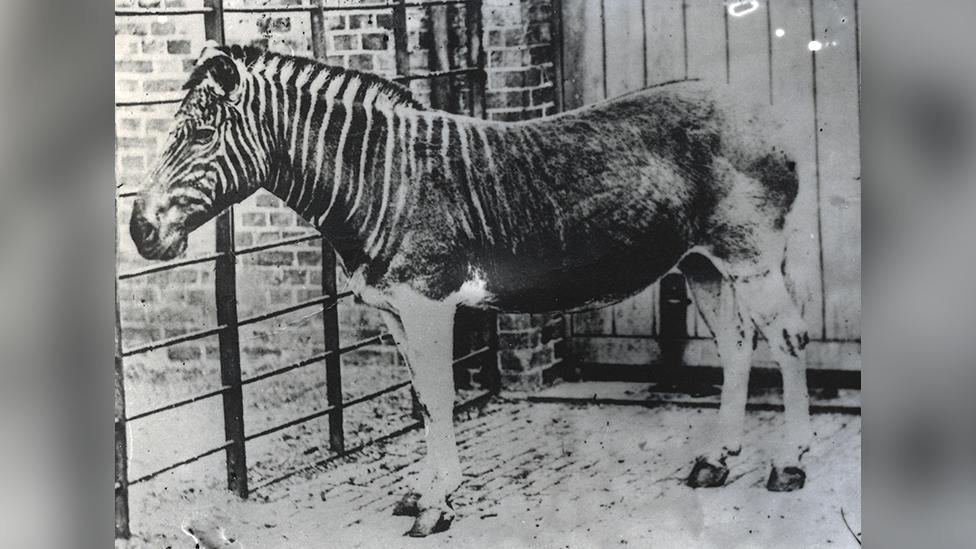

The quagga looked like it was part-zebra, part-horse and is now extinct

The aerial bombing of London during World War Two saw many of the city's treasures shipped out for safekeeping.

One of the world's rarest skeletons was sent from the Grant Museum of Zoology to Wales.

The extinct quagga had the appearance of being half-zebra, half-horse, and died out in 1872.

The skeleton was sent to Bangor University but on its return the museum found one of the limbs was missing and its whereabouts remain a mystery.

Tannis Davidson is curator at the museum which is part of University College London.

She said when it was first sent to Bangor, Gwynedd, no-one realised it was a quagga.

That only came to light in 1972.

Until then it was thought to simply be a zebra or a horse.

What is a quagga?

Equus quagga quagga was once found in huge herds across South Africa until it was hunted to extinction

Charles Darwin deemed the quagga a separate species, but today it is considered a subspecies of the plains zebra

The head, neck, and upper body was reddish brown and marked with dark brown stripes

They were stronger on the head and neck, gradually fading behind the shoulder.

A broad stripe ran down the middle of its back

The underside of its body, its legs, and its tail were nearly white

The last one died at London Zoo in 1872

Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica

"It is one of many mysteries here," Ms Davidson said.

"Every specimen in the collection has an interesting mystery about how it got here.

"It would have been used by students as a zebra from 1940 to 1972 when it was identified as a quagga."

There are just seven quagga skeletons in the world - making it the planet's rarest

She urged anyone who thought they might have the missing leg to get in touch.

"Not that I want to receive 50,000 random horse legs," she said.

"If this was a crime caper I would definitely follow up this Welsh lead," Ms Davidson said.

But when BBC Wales called Bangor University they were unable to locate the runaway leg.

Tannis Davidson hopes someone knows where the missing back leg is

Senior biology lecturer Rosanna Robinson is museum curator at Bangor University's school of natural sciences.

"We wish we could give this story legs," she said.

"But the extensive catalogue of our Brambell Natural History Museum has not thrown up any 'horse' limbs which shouldn't be there, so the trail has gone cold at our end."

Ms Davidson hopes the riddle might yet be solved - though the skeleton is also missing a shoulder bone.

"It is a long-standing mystery and to have the rarest skeleton in the world fully completed again would be fabulous," she said.

- Published3 April 2014

- Published20 September 2019

- Published21 February 2019