Flint castle: History behind castle chosen for sculpture

- Published

Flint was one of the first castles to be built in Wales by Edward I

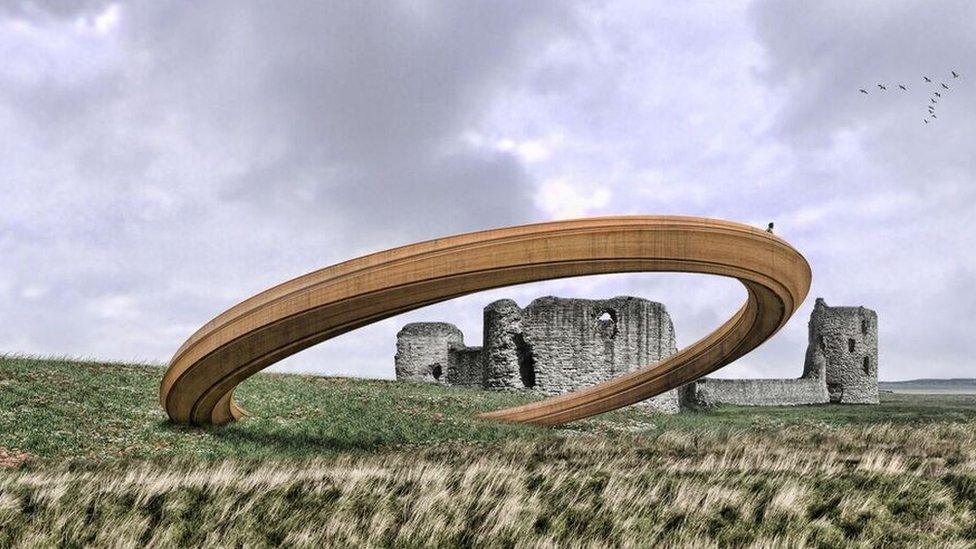

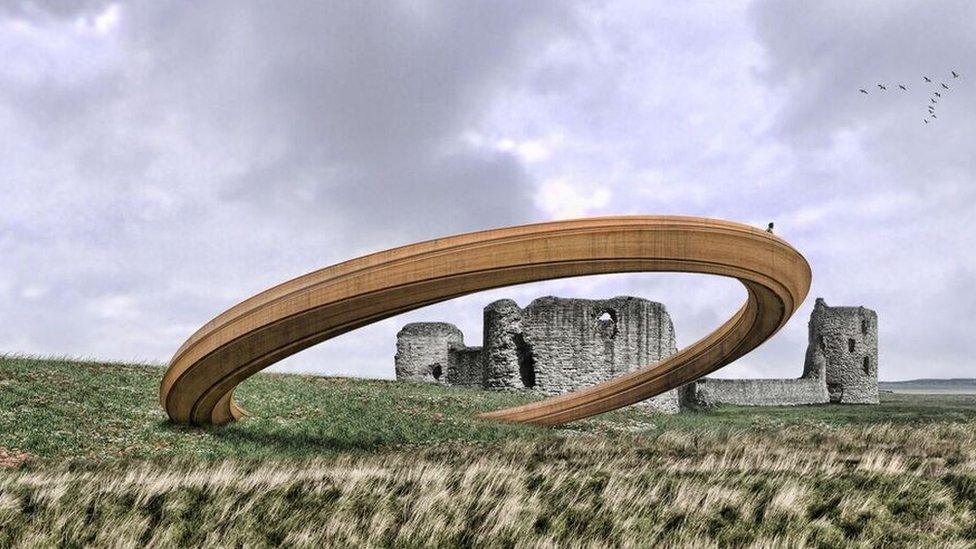

A sculpture to celebrate the "labourers and craftsmen who, some willingly and some forcibly, built Flint castle" is to be erected near the monument after an earlier plan for an "iron ring" representing Flint and other castles built by Edward I in Wales was scrapped following criticism it represented English oppression.

But why was Flint castle built? And who ended up building it, and living there and in the new town that followed? Matthew Frank Stevens, a senior lecturer at Swansea University explores the history behind the castle.

Thanks to careful medieval "bookkeeping", including costs of materials and weekly wage accounts, and the detective work of the late Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments in Wales Arnold Taylor, we actually know a remarkable amount about Flint's construction.

Flint, and her sister castle-town of Rhuddlan, were founded after the Anglo-Welsh War of 1277 to secure the route from Chester to the river Conway.

It represented a new strategy in design, where the castle and town were built together - the castle to be garrisoned by soldiers and the town to be occupied by merchants and craftsmen.

It was a project on a vast scale, and resources were mobilised from across England and parts of Wales.

In fact, the story reaches even to Italy, where Edward I secured large loans from the Ricciardi Bank of Lucca (Tuscany) to finance his Welsh ambitions, and ultimately to pay his builders' wages.

In the summer of 1277, masons were recruited from Leicestershire, Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire, carpenters were to be recruited "from diverse parts of the realm", and diggers were recruited from Warwickshire, Leicestershire, Shropshire, Staffordshire, Lancashire and Cheshire.

By July 1277, at least 1,850 workers had assembled by land and sea at the site of Flint, including 200 masons, 330 carpenters, 970 diggers and 320 woodmen, 12 smiths and 10 charcoal makers to supply them.

There they worked under the guidance of chief architect James of Saint George, castle designer extraordinaire, from Savoy, near Lake Geneva (which now divides France and Switzerland). The workers were well paid by contemporary standards.

The artwork will occupy a space of 12 square metres and visitors will be able to walk through it

The chronicle of the Welsh princes, Brut y Tywysogion, says that at first the construction site was a fortified court for King Edward and his administration "with huge ditches around it", suggesting an English workforce sheltered from hostile Welsh locals.

But Flintshire had long flip-flopped between English and Welsh control and local relations were not entirely hostile.

It is probable that the skilled workers imported from England were supplemented by Welsh labourers, attracted by the good wages on offer in an economy where they had few alternatives - there is no evidence of anyone being coerced to work on the castle.

Nonetheless, the workforce was dominated by the English. This was probably less about ethnicity, and more about available manpower.

The population of the whole of Wales in 1277 was only about 250,000, more than 10% of whom were English colonists of previous generations. By comparison, England's population was already six million.

Flint castle and town were still under construction nearly five years later, in March 1282, when the final Anglo-Welsh war broke out and prince Llywelyn ap Gruffydd's men attacked the site.

Flint castle cost about £7,000 to build

But work was back under way within a month and the main construction was finally wrapped up in November 1284, though finishing touches dragged on until 1286, some nine years after building had begun.

The whole affair, materials and workers' wages, had cost about £7,000, at a time when a worker's daily wage was somewhere between two and 10 pence a day (there were 240 pence to the pound in old money).

Many of the builders stayed on, and became Flint's first townspeople.

The king granted the town a charter in 1284, giving anyone who settled low fixed rents and big tax breaks on buying and selling just about anything, throughout England and Wales.

When a tax assessment of the town was made in 1293, there were 76 households but only five households were headed by people with Welsh names, like Madog ap Iorwerth and Einion Cragh.

They were not the poorest taxpayers, but they were far from the richest. They lived alongside Englishmen who had probably come for work building the castle and town.

Names in the tax assessment include Adam the carter, Benedict the miner, Godfrey the carpenter and Nicholas the smith.

In 1295, rebellion against English rule broke out in north Wales and Flint was burnt to the ground.

A string of anti-Welsh ordinances were rolled out.

The Welsh were banned from owning property in Flint and other north Wales towns, and banned from holding any kind of public office.

Artist's impression of Rich White's sculpture which stands 9m high

As the town rebuilt, in 1297 the English burgesses of Flint petitioned the king complaining that the Welsh had "bought land in the town and bake and brew, contrary to their charter and custom".

This was a lie.

The original town charter had said nothing about who could live there. The people being complained about were probably existing Welsh residents helping in the rebuilding of the town but now, in the wake of the rebellion and the new anti-Welsh laws, they were no longer welcome as shopkeepers.

Almost certainly Welsh people lived and worked in Flint over the coming centuries, but the town remained staunchly against Welsh ownership of any kind for centuries to come.

This meant property confiscations against Welsh people did happen.

One example is what happened after the death of Flint townsman Richard Slepe in 1327.

He was an Englishman (probably from Shropshire) who had been in the town from its start, and had weathered being burned out in 1295.

His Flint houses passed to his daughter Agnes and her Welsh husband Adda ap Einion, but their property was confiscated by the town's English officials.

Adda and Agnes argued that "to foster peace and agreement between English and Welsh… alliances by marriage should be allowed".

But they were nonetheless turfed out by officials who claimed "to understand (of the law) that no Welshman ought to live in an enfranchised town in Wales".

Not until the 1536 Act of Union between England and Wales would Welshmen have equal rights in Flint.

So where does this leave the new monument to be erected by Flint Council to "celebrate the labourers and craftsmen who… built Flint Castle and, by extension, were responsible for the creation and growth of Flint as a town"?

The workforce was mostly but not entirely English, and many settled in Wales and became part of the new Welsh society that developed after conquest.

This was a society in which the Welsh were often second-class citizens but it was also one where the Welsh and English lived and worked alongside each other too.

It is as important to remember the marriage of the English woman Agnes and the Welshman Adda ap Einion as it is to remember the confiscation of their property.

Perhaps what any monument or sculpture should do is to help people today understand what happened with the conquest of Wales, rather than to celebrate or condemn the events of hundreds of years ago.

- Published30 October 2019

- Published8 September 2017

- Published7 September 2017