Swansea copperworks: Industry was 'Google of its day'

- Published

How part of the Swansea site looked when it was producing copper

Archaeologists are unveiling new evidence of how Swansea's copperworks were the "Google of their day".

At its 19th Century peak, the city produced 90% of all the world's copper.

Now the Hafod-Morfa works is undergoing a fingertip search of the site, to uncover some of its lesser-known gems.

Over the next few years the banks of the River Tawe will be transformed, with the renovation of the historic Powerhouse building, and the Penderyn Distillery expansion.

But before then Monmouthshire-based Black Mountains Archaeology is saving as much as possible.

The firm is also creating 3D models of everything else they have discovered from the works, before the bulldozers move in.

Managing director Richard Lewis said that people may expect that because it is a "reasonably recent site" it "should be quite straight forward".

"In an undisturbed location you'd have the 'gateau effect' of historical layers, whereby the newest material is closest to the top and the oldest furthest down," he explained.

"But Hafod has been redesigned and reengineered so many times that some of the native soil is closest to the surface, while quite recent - 1950s - copper slag is buried deep down."

He added that overall the site is 2-3m (6.6-9.8ft) higher today than it would have been at ground level when the works opened in 1809.

The remains of a bath house

Richard Lewis said the scope and nature of the finds are a testament to the vast global scale of the copper industry

South American copper was shipped to Swansea for smelting, as three times as much coal than ore was required for the process.

In 1855 daily clipper ships from Chile rounded Cape Horn in the roughest seas on Earth to deliver the rock to Swansea, and sailors who had completed the voyage were entitled to bear a distinctive "Cape Horner" tattoo.

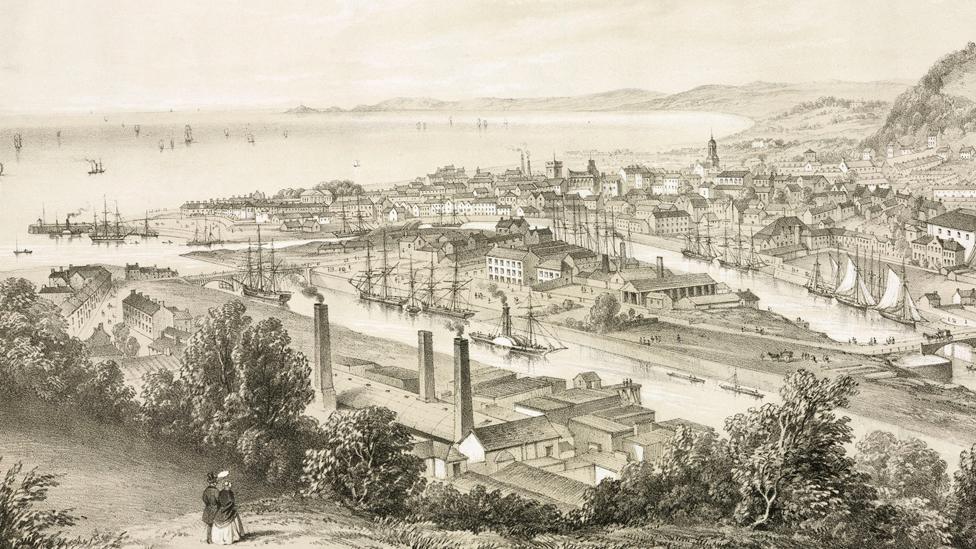

A view of the port of Swansea from the mid 1850s

Most of the copper was used for sheaving wooden ships to prevent them from rot and parasites, however some was made into bangles and necklaces which were traded for slaves in West Africa.

The finds discovered at the Hafod-Morfa works range in size from an entire furnace, to a shower block and urinals and Georgian cups, saucers and teapot.

"Considering how much upheaval there's been at the works over 200 years, it was incredible to dig out intact urinals and shower trays," said Mr Lewis.

"My personal favourite discovery was an entire flue and chimney of a long-gone 19th Century furnace.

"Articles as large as that will obviously have to be built over, but even the smaller porcelain discoveries aren't safe to be removed from the site, as they've been absorbing toxic chemicals for a century or more."

The remains of a rolling mill (bottom right), a cast house (centre left) and the gable end of a laboratory building (centre top)

Mr Lewis said the scope and nature of the finds are a testament to the vast global scale of the copper industry.

"A lot of what we've found was never meant to last this long; it was ephemeral, and part of a system which was developing so rapidly.

"The nearest thing I could liken it to is looking in your attic and finding a VHS player underneath a DVD player, underneath a laptop, underneath a smart phone.

"Copper was truly the big tech 'Google' industry of its day, and in one site we've unearthed two centuries of scientific progress."

- Published3 December 2018

- Published10 September 2017

- Published6 May 2015

- Published13 April 2012