Extremism: More than 250 people in Wales flagged over concerns

- Published

Estyn says experience has shown that radicalisation to violent extremism can take place in the most unexpected places

More than 250 people in Wales were flagged up to police and councils over concerns about extremism, it has emerged.

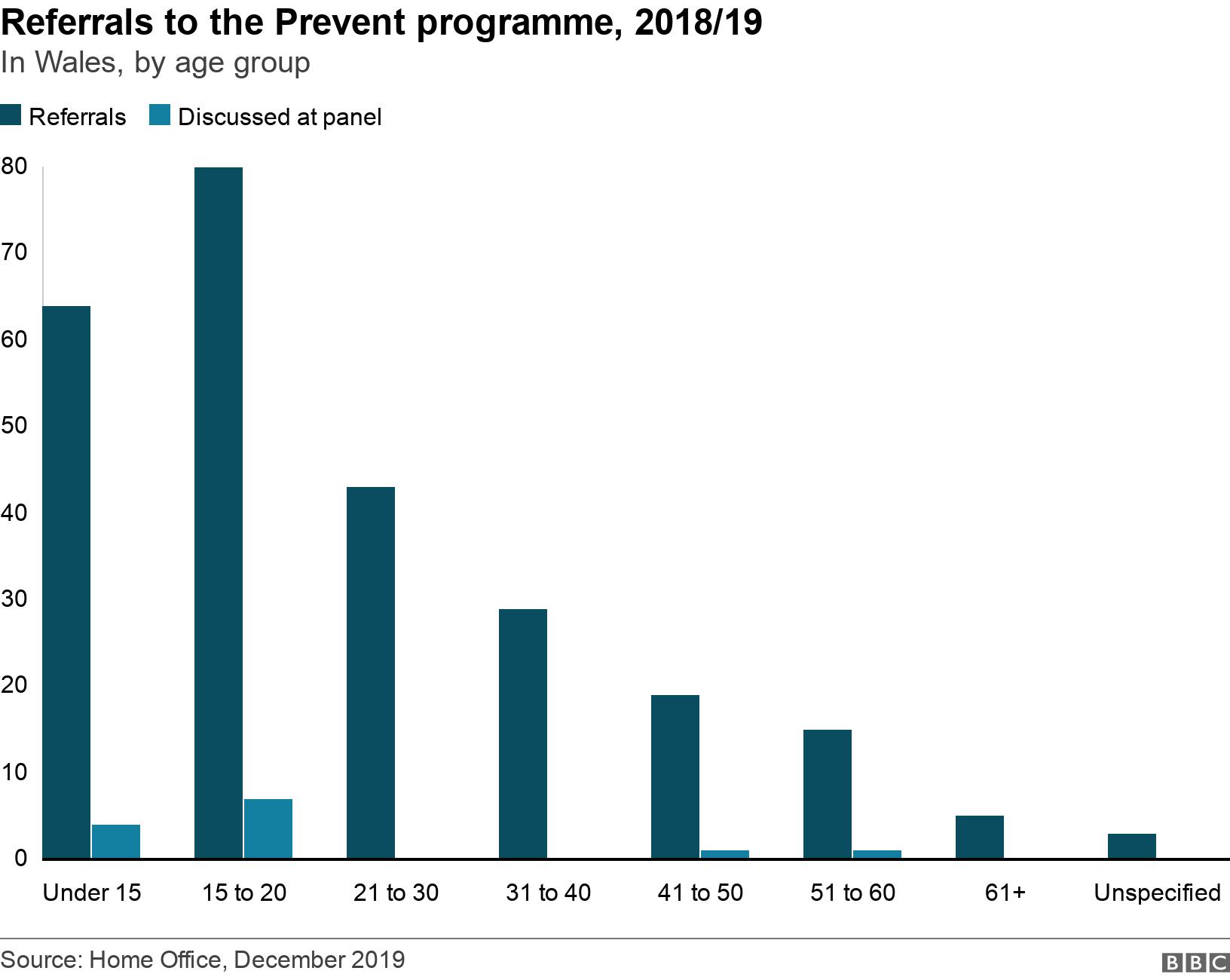

Just under half were aged 20 or younger, Home Office figures show.

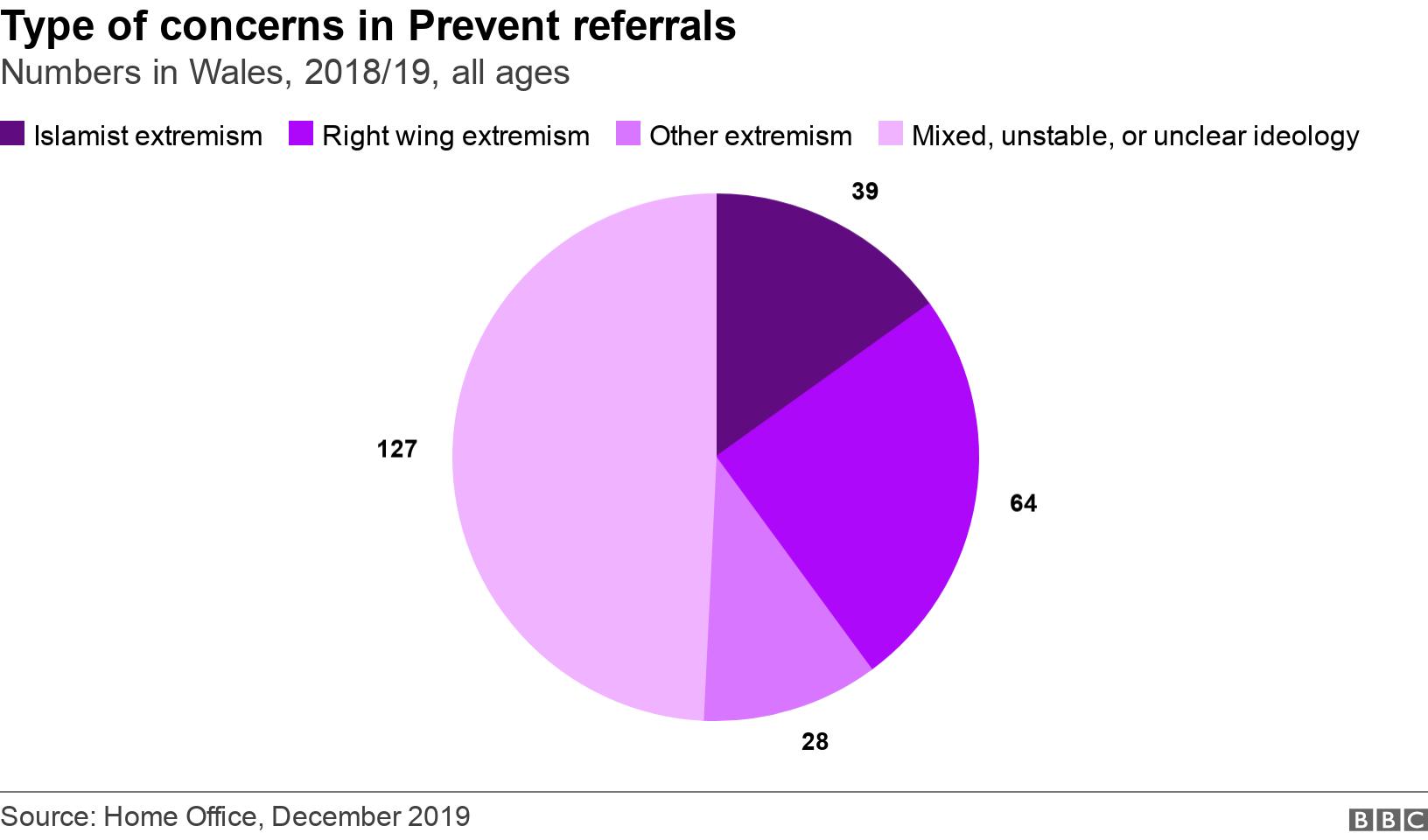

Right-wing extremism accounts for 24% of all referrals, while 15% are related to Islamist extremism.

An education watchdog warned that some schools could miss early opportunities to address extremism because they do not think it is relevant.

Estyn wants it acknowledged that radicalisation and extremism are "real risks" to pupils in all schools.

Schools are required to protect pupils from radicalisation and the Welsh Government said Wales' new curriculum will teach youngsters to "critically evaluate" information they are exposed to.

Last year 258 people in Wales were flagged up to police and councils over concerns about extremism.

The figures are highlighted in a report by the education and schools inspectorate says most schools do not do enough within their curriculum to build pupils' resilience against extremist influences.

It said leaders in most schools had an understanding of their role and responsibilities with regard to radicalisation and extremism.

But "in a minority of schools, leaders do not perceive radicalisation and extremism as relevant to their school or surrounding area", and that meant "staff in these schools may miss an opportunity to identify and address early concerns about a pupil".

It also said:

Schools should record and report all incidents of racist language and racial bullying properly, and offer suitable support and challenge to victims and perpetrators

Most schools have policies on staying safe online but only a minority mention the risks from radical and extremist materials

School 'lockdown' procedures are currently in development across Wales as part of a requirement to have an emergency plan.

Jassa Scott, strategic director at Estyn, said schools played a key part in safeguarding some young people from radicalisation.

"Radicalisation to violent extremism can happen in the most unexpected places," she said.

"Schools should be tuned into bullying, in particular the use of racist language and inter-racial conflict between pupils which can indicate radical or extremist views."

What can schools do?

Schools can refer to 'channel' panels, set up under the UK government's anti-terrorism Prevent strategy.

They are chaired by the council and include health and education bodies, and the police.

Home Office figures show 258 people in Wales were referred to them over concerns about extremism between April 2018 and March 2019.

Thirteen of these were discussed by the panel and 12 went on to receive support.

These rates were amongst the lowest when compared with English regions.

In Wales, just under half of referrals are for people aged 20 and under and education is the highest source for referrals.

Right-wing extremism accounts for 24% of all referrals, while 15% are related to Islamist extremism.

The report said there had been an "increase in individuals attracted to violence where the specific ideology driving the behaviour is less clear", accounting for 49% of referrals.

This was often referred to as the 'Columbine effect', Estyn said, named after the 1999 school shootings at Columbine High School.

What sort of things are flagged up?

They have included extremist comments in class or course work, sharing extremist material on social media or pupils refusing to be friends with other pupils due to race or religion.

In one school, a pupil's answer in a mock examination raised concerns along with a separate comment in a religious education lesson.

Another example saw a change of attitude in a pupil who was increasingly critical of anyone from a non-white background.

They discovered that a close family member who was radicalised had recently been released from prison.

What do schools teach?

These 10-year-olds at Roath Park Primary are talking here about issues around racism and sexism

Through Personal and Social Education (PSE) and subjects such as religious education and history, all schools cover other cultures and religions and the impact of oppressive political regimes.

But Estyn said it can be superficial if schools avoid more difficult issues.

The report said a minority of schools do not teach about Islam, sometimes due to pupils not wanting to learn about it, parental objections or teachers not wanting to teach the subject.

It said in one school, half the parents objected to their children visiting a local mosque due to their views about Islam.

Jonathan Keohane, head teacher of Roath Park Primary School, welcomed the Estyn report and said since 2016 it has worked with two other Cardiff schools and others in Germany and the Czech Republic to develop a challenging extremism project., external

He said schools were more than the standard subjects they teach and it was about taking on contentious issues, which come up on social media or in the news, and might have been brushed aside in the past.

"Our children need to have that safe space to talk and our staff need to be skilled to have that difficult conversation with children when they arise," he said.

"It's about being proactive and giving our children the skills and knowledge to live in an ever-changing world."

What does the Welsh Government say?

It said Wales' new curriculum would focus on providing pupils with skills to "critically evaluate the information they are exposed to, including online".

A spokesman said: "We have provided funding to the Welsh Extremism and Counter Terrorism Unit and partners to develop resources to prevent radicalisation, to be delivered in schools by school beat officers.

"We have accepted the report's recommendation and will continue to work with our partners to support schools in building learners' resilience when confronted with radicalised and extremist influences."

- Published27 January 2020

- Published4 June 2018

- Published9 November 2017

- Published4 June 2017

- Published9 November 2017