Coronavirus: Swansea University's WW2 lessons for post-Covid role

- Published

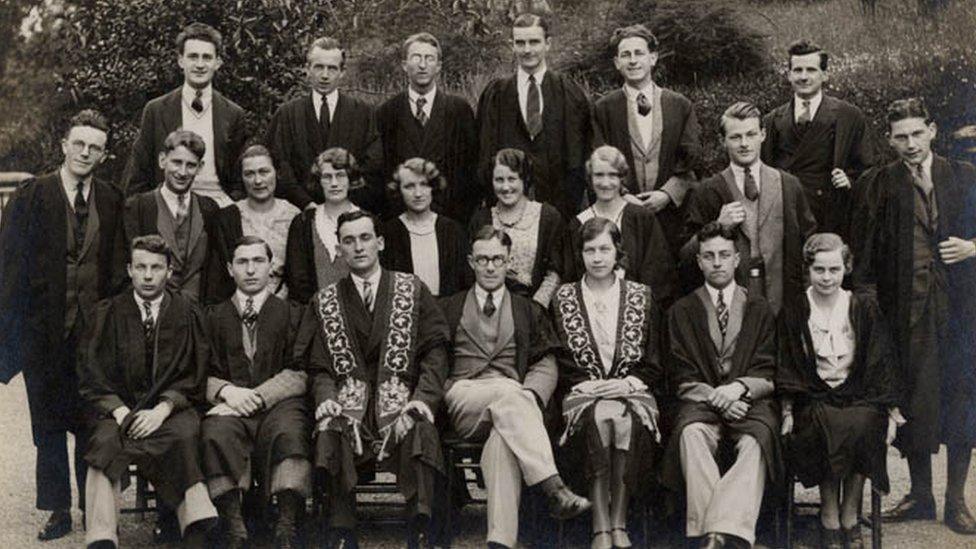

During World War Two, students joined the Home Guard and were responsible for patrolling Swansea Bay

Universities can draw on the lessons of World War Two to stay relevant in a post-coronavirus world, according to a university researcher.

Dr Sam Blaxland, author of Swansea University: Campus and Community in a Post-War World, looked at how it adapted from war to peacetime.

In 1945, Swansea's student population had more than halved to 342 and focused on researching explosives.

By the 1950s, it was catering to the needs of a shell-shocked nation.

"During the war, the university's Singleton Campus was untouched by the three-night blitz in 1941 and so remained the scene of vital war work, becoming home to Imperial College London's Royal School of Mines and the government's Department of Explosive Research," said Dr Blaxland.

"Students also joined the Home Guard and were responsible for patrolling Swansea Bay."

Following VE Day, the university's attention switched to dealing with the needs of the local community; helping families who'd lost loved ones and wage-earners, and retraining soldiers who had often spent their entire working lives in the armed forces.

Universities need to find ways they can help put society back together, said Dr Blaxland

According to Dr Blaxland, the years after the war were particularly interesting as they reflect what institutions like Swansea University might do when the worst of the current public health crisis is over.

Like universities across the country, Swansea has been concentrating on how it can help to counter the pandemic, from developing new types of ventilators to manufacturing hand sanitiser and PPE.

Its College of Engineering and Healthcare Technology Centre helped design a ventilator that can be built quickly with local parts and used for patients with severe coronavirus.

But Dr Blaxland argues that soon the attention will have to switch to dealing with the aftermath of coronavirus, moving to psychology research such as treating the trauma people have suffered, training new social workers, getting the economy back on its feet with new green industries, and medical studies into ways of preventing a second wave.

"Hopefully we are over the very worst of this outbreak, but that is just the start," he said.

"Swansea, and all other universities, need to start looking now at how we can help put society back together after such a massive upheaval.

"The war and its aftermath showed how Swansea University responded to a major event with creativity and determination and the same is true today."

He added that with student numbers and income set to be very stretched, staying relevant to the needs of the local community is the only way in which Swansea can survive.

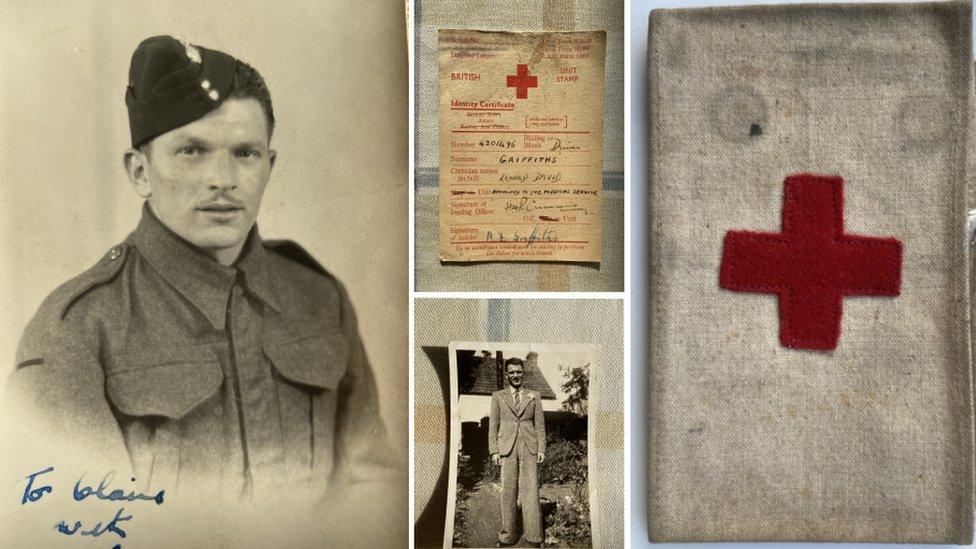

A team of Swansea doctors and engineers has already designed a new ventilator that can be built quickly with local parts and used for patients with severe coronavirus

For that to succeed, Dr Blaxland believes there are more lessons to be learnt from the post-war era, and that the students themselves will have to be at the heart of the change.

With Black Lives Matter foremost in people's thinking today, Dr Blaxland highlights the difference a strong student voice made in the immediate post-war era.

"In the 1950s, and particularly in the 1960s, you start to see a growing student voice.

"Prior to the war there was a paternalistic system of 'in loco parentis', whereby many aspects of student life were determined - top-down - by the university, but after the age of majority was lowered from 21 to 18, students start exerting their opinions on what the university should be and the things which matter to them.

"Student voices have never been more important, and over the next few years their help in shaping the future of our universities, and society in general, is going to be vital in recovering and improving all our lives."

Dr Blaxland added it takes more than study to help heal the wounds caused by a national trauma - a lesson which can be learned from Swansea University's post-war engagement with local communities.

He said: "From the early 1950s, the university welcomed a series of United Nations Social Welfare Fellows to Swansea, where people from dozens of countries around the world studied for qualifications in social work.

"This involved much more than study. They worked closely with people, businesses and companies in the local region to gain an understanding of the particular needs and problems of the region.

"They formed good relations with many townspeople, meaning that it was a cultural, as well as an academic, exchange."

- Published14 April 2020

- Published27 March 2020

- Published14 April 2020

- Published22 January 2020