From Yemen to Wales: 'I thought I would die under that lorry'

- Published

Mujahed Aqlan has not seen his family since he fled Yemen aged 15

Sixteen-year-old Mujahed Aqlan had never been so scared. Not even when a group of gunmen had showed up at his home and threatened to kill his entire family.

As he stood shaking, steeling himself to run under a lorry and squeeze himself into a tiny space between its two massive tyres, he was overcome with feelings of anger and loss.

He had fled Yemen a few months earlier after it became clear to Mujahed's father that his eldest son, a Sunni, would be a target for Houthi rebels fighting in the country's bloody civil war.

Speaking to the BBC, 'Muj', now 23, relived his perilous journey from Yemen to Cardiff, where he has been granted asylum and played football for Wales in last year's Homeless World Cup.

It was a "simple life" in Yemen, he said, but he had felt privileged to live a happy life with family and friends who loved him.

"I was thinking 'why am I here?'," he said, recalling the build-up to his first attempt at stowing away on a lorry from Turkey to Greece.

"My situation was very good in Yemen. I had money and nice people around me - I had everything I need. It's a simple life but I felt rich."

Yemen's civil war has raged for over five years, and led to the world's worst humanitarian crisis.

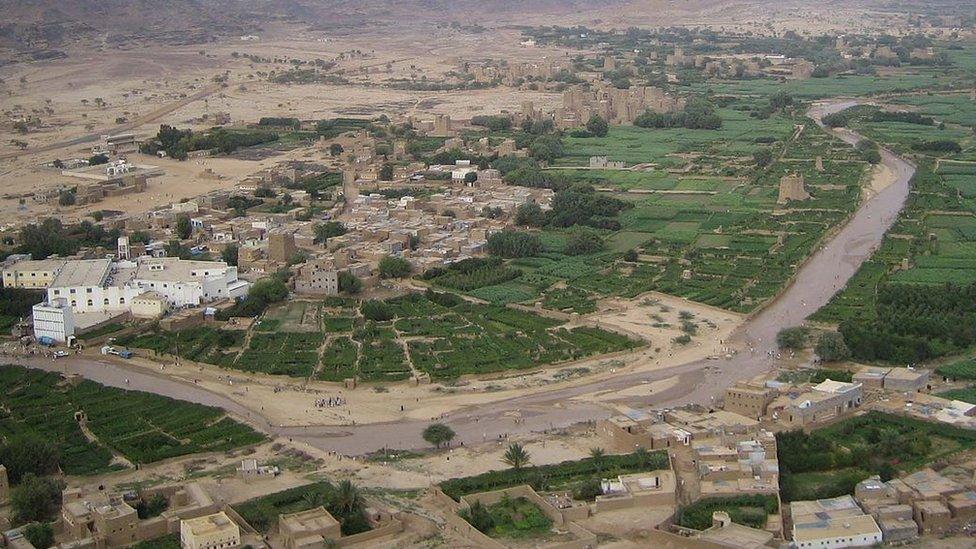

Muj is from the village of Dammaj, in north-western Yemen

In 2014, aged 15, the war came knocking on Muj's front door.

When his father wasn't home, in the village of Dammaj, north-western Yemen, Muj assumed the role of man of the house.

He was there with his mother and seven younger siblings when he heard violent banging at the door.

He answered to find two men holding large guns, demanding to know where his father was.

Muj's father was a sheikh and landowner, meaning he was often the subject of intimidation and blackmail. But nothing could prepare Muj for what happened next.

"They tried to push me and they shot a lot," he explained.

Houthi rebel fighters entered the capital Sanaa in September 2014 and took full control in January 2015

The men had aimed at walls rather than Muj or his family, but it was a terrifying ordeal.

He summoned up the courage to challenge the men and they left, but they'd come to send a message to his father - that his family wasn't safe.

This event would change the course of Muj's life.

A tactic of the Houthis, Muj explained, was to kidnap boys aged just 13 or 14 and hold them ransom or make them fight.

"When they came they said 'if your dad doesn't come, I'm going to take you and you will be fighting against your dad'," he said.

It wasn't a risk his father was willing to take. About a month later, Muj was on a flight to Turkey with only a rucksack and a small amount of cash.

It was an emotional farewell and Muj cried for most of the flight. He hasn't seen his family since.

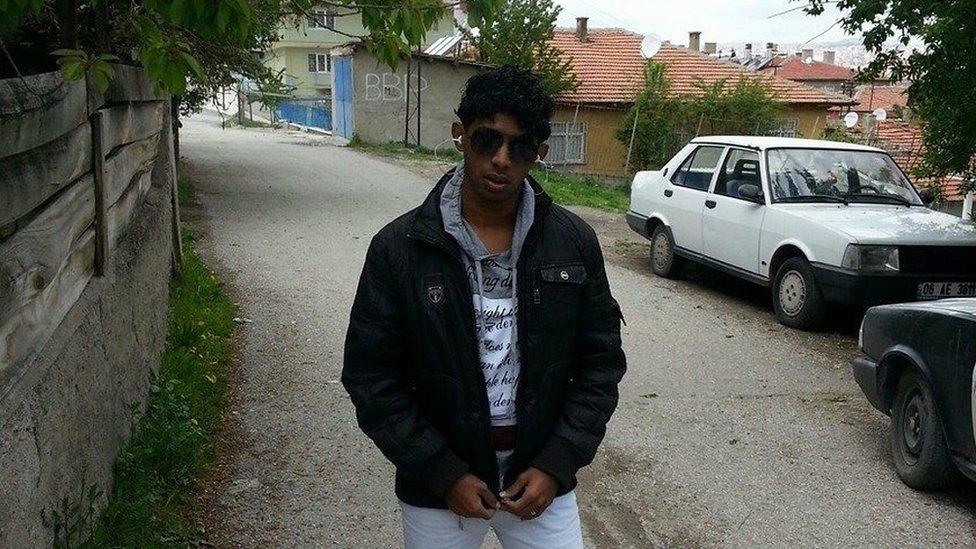

Muj, pictured here in Turkey, became deeply homesick and concerned for his family's safety

Speaking to Muj on his arrival in Turkey, his father was unable to reassure him - he was homesick and deeply concerned for the safety of his family.

"He tried to make me calm, saying 'don't worry, we will come, just go study and do well'," said Muj.

"I really missed my family every day, every night. Every night I start to think about them... what are they going to do?

"Why do I have to be here? Why do I have to go to Europe?"

He made good friends with other migrants along the way and they had one goal: get to Europe.

There were two ways of making it from Turkey, but only one of these was available to Muj.

With little money, Muj couldn't afford the safer option of catching a flight to Europe

He couldn't afford a flight, so he would have to try and stow away on a lorry heading to Greece by ferry. But it was dangerous.

"I saw people trying to go under the lorry and I thought, 'what's going on here?'," Muj recalled.

"I didn't understand - why did I have to do this? I was really scared."

While he made it to Greece, it was a tough environment for migrants there so he wanted to get to Italy as soon as possible.

Muj said he was filled with shock and fear the first time he saw how dangerous it was stowing away on a lorry

Muj had managed to get on another lorry in Greece and headed to Italy. As the ferry pulled into Bari port in the middle of the night, he felt an overwhelming sense of relief.

But just as the lorry was about to pull off the ship, his relief turned to horror as the the driver knelt down and spotted him clinging on to the underside of the lorry.

Having been in this situation a few times, Muj knew the driver would either demand all of his cash or hand him over to police.

But instead, something strange happened. The driver looked at Muj, signalled it was safe to go and got in his cab.

He couldn't believe his luck, but he decided he would wait for the lorry to leave the port before jumping off.

But the lorry kept going, and going - for 30 long minutes.

"Every time the lorry moved, my hands slipped. I didn't have enough power to hold my hands," Muj explained.

"My left hand slipped because[I was] tired - I hadn't eaten. As soon as the driver turned right, my hand slipped.

"And I said: 'I'm dying'. That's what I was thinking. Someone was saying inside me 'open your hands'. And I said 'no, no, nearly done, nearly done' and hold so strong."

When the lorry stopped, Muj let himself drop on to the road, slowly got to his feet and stumbled over to some grass where he lay under a tree, relieved to be alive.

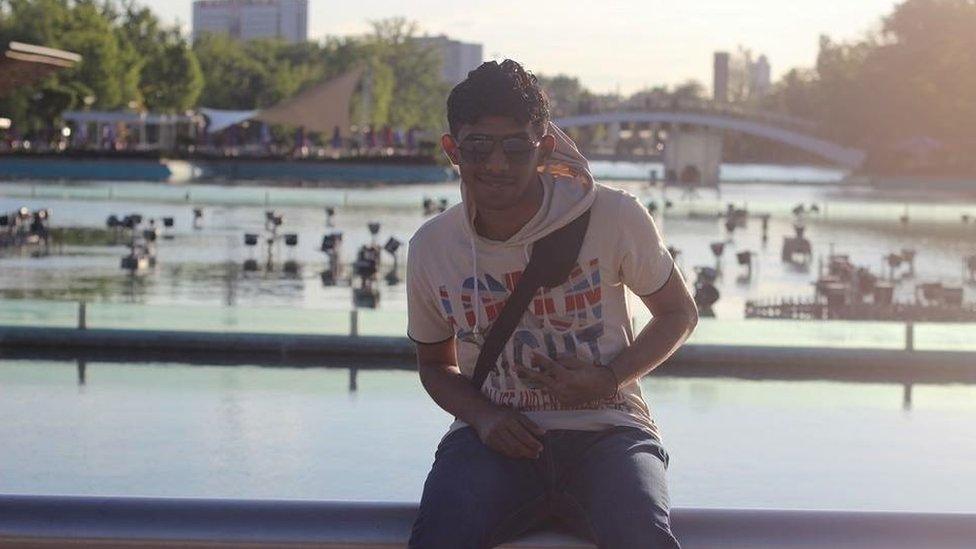

Despite making it to the UK, a civil war and famine gripped Yemen and Muj worried about his family, who he hadn't spoken to in years

Muj became seasoned in this grimmest of tasks, and it help him to get to the UK.

He had not been in contact with his family for three years.

With the Yemeni civil war and famine all over the news, he wondered whether his family had made it out alive.

Muj was otherwise in a good place - United Welsh housing association had found him a home in Cardiff and he had been selected to play for Wales in the Homeless World Cup in Bute Park, Cardiff.

Muj had been selected to play for Wales at the Homeless World Cup - but the fears for his family hung over him

But the nagging worry over his family's safety was a constant source of pain.

Then, out of the blue, Muj received a message on Facebook from a man he didn't know, claiming his family were safe in Saudi Arabia.

He didn't allow himself to get excited. Muj gave the man his phone number to pass on and thought nothing more of it.

But a couple of days later, before the World Cup, he received a phone call. It was his family.

Hearing from his family days before the tournament made Muj feel like "superman"

"I spoke to my family, I spoke to my dad, and he said he was okay and my family are all okay, so I feel like almost superman," he said.

"I said 'look, the nice days are coming for me'. It was amazing when you got that feeling, when you were playing in a game and nothing could stop you."

Muj hasn't been able to see his family in person yet - he had been saving up but coronavirus dented his earnings and made travel impossible.

But when he finally does see them again, he'll have two new siblings to meet.

"I really, really miss my family. For three years I have been thinking 'where is my family?'," he added.

"I need my family - I want to live with them, I want to live with my little sisters, my brothers. Seven years is not easy - not easy at all."

Muj continues to save money in the hope he can fly to see them in Saudi Arabia when the coronavirus pandemic is over

The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

- Published3 August 2019

- Published27 July 2019

- Published25 July 2019

- Published11 January 2019