What do Medieval carved stones and Celtic crosses in Wales symbolise?

- Published

The stones are a familiar sight, especially in north and west Wales

You may not have spotted them but there are more than 500 early medieval carved stones in Wales.

The majority are Christian, and range in date from the Roman withdrawal in 410 to the Norman Conquest in 1066.

Most are memorials to important people of the day.

But a few, such as a cross-carved stone from Marloes, Pembrokeshire, may give thanks for a successful sea crossing or in the case of the Pillar of Eliseg, Denbighshire, mark meeting places.

However, what is most fascinating about them is the variety of languages used for their inscriptions, according to Prof Nancy Edwards, Chair of Commissioners for the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (RCAHMW).

"These stones show the development of language in what we now call Wales," she said.

"In the 5th Century, there were three languages in use: Latin - still spoken after the end of the Roman occupation and two Celtic languages - British, which would go on to develop into Welsh, and Irish, which shows a strong Irish presence in south-west Wales.

"By the 9th Century, we start to see something which is more recognisably Welsh as we'd know it today, and after that come signs of English and Norse influence, particularly in north-east Wales."

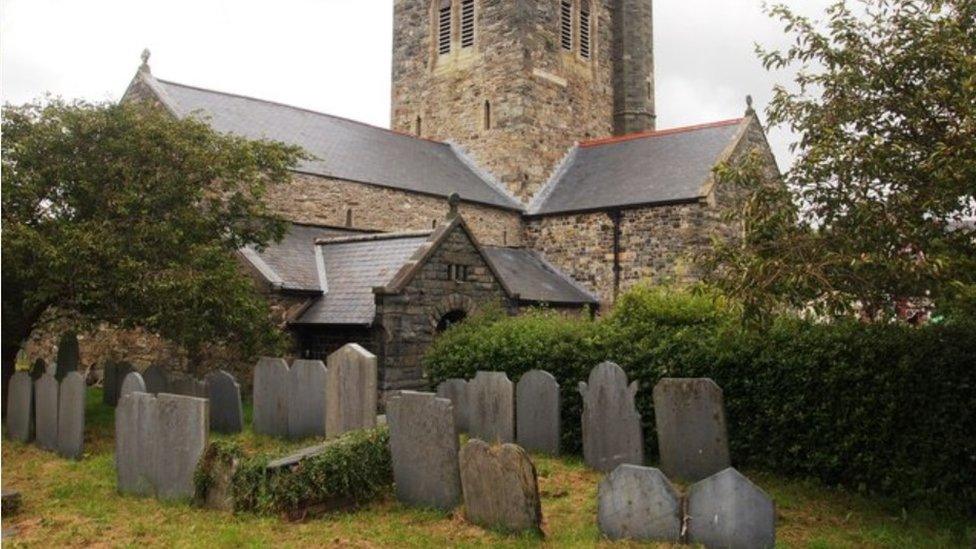

Two inscribed stones at St Digain’s Church, Llangernyw

The tradition of carving stones dates back to pre-Roman times, and indeed at Llanfaelog on Anglesey there is an ancient standing stone with a Latin inscription added in the 6th Century.

Those from the 5th Century are often not religious in tone, and instead focus on recording the kin of the remembered person.

During the 7th Century, these went out of fashion and graves were marked by simple stones with crosses, often bearing no name or inscription at all.

However, from the late 8th Century onwards, as the church became more powerful, large decorated stone crosses were also erected, mostly on monastic sites but sometimes in the open countryside, and inscriptions began to make a comeback.

Tourists to Gwynedd and Pembrokeshire may have noticed stones

Prof Edwards, who is also professor of medieval archaeology at Bangor University, has picked out three of her favourites in a post for the RCAHMW.

The first is the Bridell Inscribed Stone - dating from the 5th Century, it stands in the churchyard of St David's Church, Bridell, Pembrokeshire.

It is inscribed using the Old Irish ogham alphabet, with each letter consisting of one or more strokes carved across the angle of the stone from bottom to top.

The cross in the circle was added later and was probably made with the aim of Christianising the monument.

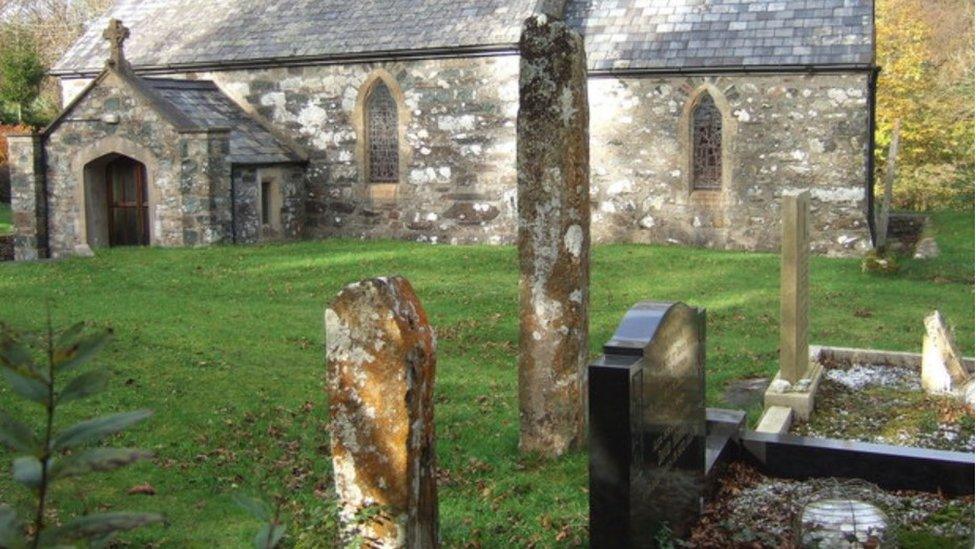

Two stones carved with 9th Century crosses are in the graveyard of Pontfaen church, Pembrokeshire

"The inscription reads: Nettasagri maqi mucoi Briaci, and commemorates a man called Nettasagri who was the son of the kin of Briaci," she said.

"It's one of a cluster of such stones in south-west Wales, and is significant as it shows that not only did the Irish come to Pembrokeshire, but they stayed.

"Creating such lasting monuments also indicates ownership of the land."

Stones are in the graveyard of St Cadfan's Church, Tywyn

The second is the Tywyn Stone, now standing in St Cadfan's Church, Tywyn, Gwynedd, it was originally placed in the cemetery sometime in the 800s.

Prof Edwards believes it was unique amongst Wales' carved stones for a number of reasons.

She said: "Firstly, it is the only stone of this time to be inscribed in Welsh, Latin being the language of the church in the 9th Century.

"Secondly, it is a very rare example of a stone dedicated to women: Tengrumui, wedded wife of Adgan, and Cun, wife of Celen.

"Lastly, the words of the inscription express grief in a way we might recognise today.

"The phrase tricet nitanam means 'a mortal wound remains'; in a time when ideas were developing about the Christian afterlife, it was more usual in Latin inscriptions to make a formal request for a prayer for the soul of the person commemorated."

'Warrior cross'

Prof Edwards said the Maen Achwyfan Cross also highlights Maen Achwyfan (St Cwyfan's Stone), which dates to the 10th Century, and stands in a field near Whitford, Flintshire, possibly the site of an early meeting place.

Its decoration is of a Viking type, and it has links with other crosses along the north Welsh coast and on the Wirral.

"This is interesting as it shows the Viking influence on north-east Wales, at a time when the land west of the River Dee was contested by the English, Vikings and Welsh," she said.

"The carving on the cross of a warrior armed to the teeth, possibly surrounded by water, also points to a melding of Christian and pagan Norse heroic imagery at a time when the Vikings had only recently converted."

- Published8 October 2018

- Published6 March 2014