World War Two: 80 years after sinking of child evacuee ship

- Published

The City of Benares had been used to sailing in the Indian Ocean but this was its first Atlantic voyage

"I am very distressed to inform you that in spite of all the precautions taken, the ship carrying your children to Canada was torpedoed on Tuesday night, September 17th.

"I am afraid your children are not those reported as rescued and I am informed that there is no chance of there being any further lists of survivors from the torpedoed vessel."

This letter arrived at the homes of 77 children - 12 in Cardiff and Newport - on the morning of Friday 20 September, 1940. A week earlier, the Ellerman liner, City of Benares, had left Liverpool, with groups of child evacuees from working class areas of the country among those on board.

The Benares disaster happened in the mid-Atlantic, 600 miles (965km) west of Ireland. The ship, carrying more than 400 passengers and crew, included a precious cargo of 90 evacuees under a scheme which would give them a chance of spending the rest of the war in safety with families in Canada and the United States.

Most were from London, which was suffering the most intense bombardment from the Blitz. One family had lost their home and belongings only days before the ship sailed.

Others came from Sunderland and Liverpool.

Aside from the emotional tug of separation across thousands of miles, parents weighed up the balance of risk of their children making a potentially dangerous voyage - or staying at home.

The Benares was the flagship of the line, a standout craft among a jumble of 19 vessels in convoy OB 213. The children faced lifeboat drills but otherwise were able to enjoy games, activities and good food served by Asian stewards in pale blue uniforms, more used to cruising in the Indian Ocean.

This was the ship's first, and it proved, final Atlantic voyage.

There was always going to be danger but a combination of factors made this tragedy arguably greater than it needed to have been.

The Benares had a Naval escort - led by HMS Winchelsea - but by the morning of 17 September, 300 miles (482km) west of Ireland, it had left to pick up a convoy of incoming ships.

The ship was built to be faster than others in the convoy and Capt Landles Nicholls was under orders that, by 12 midday, he was to have dispersed the convoy and pushed on full steam ahead.

But also on board was the convoy commodore Admiral Edmund McKinnon, a World War One veteran out of retirement, who was seen arguing with Nicholls and insisting the convoy stayed together until midnight.

City of Benares at its launch in 1936

By midday, the German submarine U48 - given licence to roam beyond the usual U-boat range - had spotted the convoy. Bad weather intervened and it decided to lurk until darkness fell.

At 22:00, it fired two torpedoes at the Benares and missed but, undetected, a third was fired a minute later and hit the ship's aft.

One child was killed in the explosion but the others, alongside their escorts, reached their allotted lifeboats.

But more problems arose and they would prove fatal.

The children themselves had life jackets but many were dressed in pyjamas and had not slept fully clothed, as ordered. Someone had relaxed that rule.

Launching the lifeboats themselves in a 40ft drop, as the ship listed, in rough weather and in the dark, was difficult and many filled with water or capsized.

Two radio operators managed to send a distress message - and within two hours, the HMS Hurricane, 300 miles (482km) away, was under instructions to search for survivors.

The convoy, under risk from further U-boat attack, had dispersed and there was no turning back to help.

Those in the lifeboats faced desperate hours.

Ralph Barker's Children Of The Benares book in 1987 drew on survivors' stories to give a vivid account of the vulnerability of the children, facing exposure and hypothermia and uncertainty of what lay ahead.

"Clutching the thwarts, the ropes and each other, the unfortunate occupants fought to maintain a handhold but many of them, dumb with fear or screaming with terror, were pitched headlong into the sea," he wrote.

There are stories of heroism and bravery from adult passengers. Some undertook daring rescues while others tried to keep children awake and spirits up.

Barker's book has no details of what happened to the Welsh children but all 12 perished.

Lives slipped away. One boat had just four living and 21 dead. There was a "tableau of heroism, happiness, hysteria and horror," wrote Barker.

Eventually, by the afternoon, HMS Hurricane reached the first of the lifeboats and rafts.

But 256 passengers and crew - including 85% of the evacuee children - were lost.

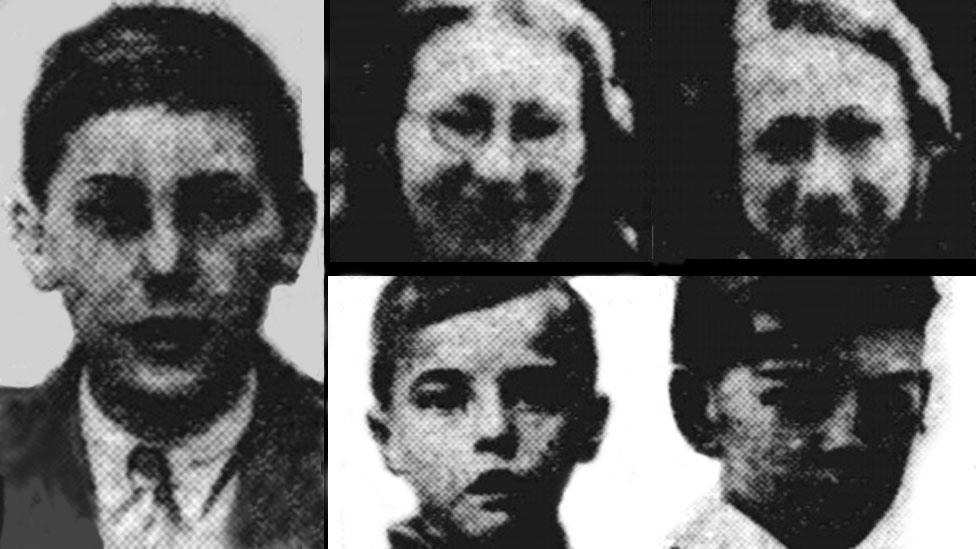

John Pemberton, 10, a keen swimmer, did not survive the disaster

Seven of the Welsh children to die were from Newport.

Ten-year-old John Pemberton was a member of his local school choir and a keen swimmer.

His younger sister Pat was still a baby when he died but her parents were obviously traumatised by what happened.

"The circumstances of John going to Canada were never discussed nor what happened," she said. "I think it was far too painful for them."

The Moss sisters were described as "very popular'

Sisters Rita and Marion Moss, aged eight and 10, were both pupils at Malpas Primary School. Elder sister Aileen, 12, was at secondary school.

All were regulars at the local Sunday school, while their father was a first-aider and drove an ambulance at a local chemical works.

Head teacher Harold Hiley described the girls as "very popular" pupils.

Anita and Billy Rees were among the siblings who were on the Benares together

Billy and Anita Rees, 12 and 14, were the children of a local optician. Billy was known to sing in the church choir; Anita was said to be quiet, very friendly and had spent time knitting comforts for the troops.

She had been at the same school, Newport Secondary for Girls, as Aileen Moss. Aileen was described by her headmistress as "rather shy" but "always helpful".

Roger James Poole, 11, son of PE teacher Percy Poole, of Allt-yr-yn Avenue, Newport, was described as a boy of "exceptional ability" by the head of Newport High School, which he had joined a year before.

Shaun McGuire is a wartime researcher who has curated their details as part of his online memorials to casualties in Newport., external

"You feel for the parents, who sent them off in good faith and with the aim of protecting them - as a father, grandfather and great-grandfather, you can really appreciate what they must have gone through for the rest of their lives." said Mr McGuire.

As for the decision to send them, no-one had the gift of hindsight.

"Newport did suffer from the Blitz - not as much as Bristol or Cardiff but there were casualties, including children," added Mr McGuire.

Leighton Ryman (left), the Lloyd sisters Nesta and Peggy, and Lewis and Jimmy Came

In Cardiff, parents were told the news in visits by Canon David John Thomas, rector of Canton.

Nesta and Peggy Lloyd, 12 and 14, were the youngest children of Jim, a nurse, and his wife, a Sunday school superintendent from Wellington Street in Canton.

They went to Canton High School, where two friends Dilys Percy and Isobel Jones had survived the torpedoing of the first "children's" ship from Liverpool, SS Volendam, to Canada on 30 August.

Dilys and Isobel, dressed in coats, slippers and wearing their school scarves, were among 320 children who were picked up by other ships in the convoy.

"Because one ship has been torpedoed it does not follow ours will be too," the Lloyd girls had reassured their mother.

Nesta had been due to celebrate her 13th birthday on board the Benares.

Jimmy Came, 13, and his 11-year-old brother Lewis, lived in Earl Street in Grangetown. Jimmy had ambitions to become a lawyer and Lewis was known as a talented musician.

Their mother Grace had been unsure whether to let the boys leave but was reported to have made "every sacrifice" so they could go. "They were everything we had - I shall not give up hope," she said after hearing the grim news.

She and her husband Albert, a slaughter man, tried for another baby - and Leslie was born in September 1941, just a year after the tragedy. But sadly, Leslie died at home of a heart problem aged just three weeks.

They went on to have another son, born in 1944.

Leighton Ryman, nine, from Richmond Road in Roath had a father, William, away with the RAF reserve.

'I was holding on for my life'

Colin Ryder Richardson was still wearing the lifejacket his mother gave him when he was eventually rescued

One of the 20 child survivors was Colin Ryder Richardson, 11, who had been evacuated from London to a farm at Llanellen near Abergavenny, Monmouthshire, at the outbreak of the war.

His parents then arranged for him a berth as a private passenger - not part of the government scheme - on the Benares, to eventually stay with a family in New York.

Colin remembered a "beautifully fitted ship", and enjoyed being on deck.

He was nicknamed "Will Scarlet" because he was always wearing a red life-jacket, given to him by his mother, who had instructed him to wear it at all times.

Colin took a schoolboy's interest in the Royal Navy and remembered how slowly the ship was sailing, because it was held back by others in the convoy.

He was "amazed" when they were told the Naval escorts had gone, on the day before the Benares was torpedoed.

"I was disappointed to think the escort had gone, I could see the reasons that they were short of ships and in a day or so we'd be picked up by Canadian destroyers the other side," he recalled in an interview 60 years later for the Imperial War Museum archive.

"So I wasn't at all surprised when we were torpedoed. I was in bed, just about to go to sleep."

Colin Ryder Richardson, on a BBC Timewatch programme, said they had a gruesome task of clearing the lifeboat of bodies as people died

He was lucky because his cabin was on the other side of the ship and with his lifejacket over his pyjamas he went to his allocated lifeboat, which was one of the first to launch on a very stormy night.

'So cold'

"We were soon full, the ship's carpenter [Angus Macdonald] was in charge of our boat," he recalled. "A soon as it was lowered it filled with water.

"I soon had another problem, holding on to the seat to prevent myself being taken out of the boat altogether. The ship by now was sinking and we had to get the boat away from it."

He said there was a lot of confusion in the dark, going up and down on enormous waves, with people - adult passengers and crew - in the water trying to hang on to the lifeboat "but they just slipped away".

Colin had been sitting next to a nurse but she died as they held on to each other.

After being persuaded to let her body go, Colin clung on to his seat - the lifejacket working against him as it buoyed him up.

"I was so cold, I couldn't move my arms and legs and was holding on for my life."

Dawn came and he could see wreckage and other lifeboats, some upturned and was "watching people die left, right and centre".

"There were only three or four of us left -[out of about 40 or 50 in the lifeboat] when we were picked up at four o'clock in the afternoon."

After his rescue, Colin arrived back with the other survivors in Glasgow and his mother travelled by overnight train to meet him. His father, a lawyer working in London, was one of the last to know when he saw Colin's photo in a newspaper.

"I eventually came back to Monmouthshire and tried to pick up life, going back to school. There were a lot of offers in America from people to go again but I said no."

Colin, who died in 2012, said he was uncomfortable with being labelled a hero, after receiving a King's commendation for helping keep morale up on the boat during their harrowing 16 hours.

He was too upset to talk about it with his parents and was deeply affected after witnessing so much "tragedy and death" at a young age.

Heinrich Bleichrodt, the U-boat commander who sank the ship, was acquitted of war crimes after the war. He claimed he did not know children were aboard and insisted he had followed rules of military engagement.

Children of the Benares reunited - a meeting of survivors for a BBC Timewatch programme

Perhaps the real tragedy of the Benares was how even those who were rescued were affected by it.

Reunions with other survivors from the early 1980s led to conversations about their experiences, which had been "stamped on their personas".

Colin said the grief stayed with him, it was "ingrained and indelible" and his whole life was trying to live with it.

- Published17 September 2010

- Published17 February 2016

- Published14 March 2020