Coronavirus: Rhondda keen to avoid long-term impact

- Published

Porth in the Rhondda in the early 20th Century

A public health officer, worried about the lack of social distancing in the Rhondda during the pandemic, bemoaned the "well-intentioned but ill-advised custom" of neighbours calling on each other, sometimes to offer support.

It was helping to spread the virus between infected and unaffected households.

This was not to do with Covid-19 but the Spanish Flu, back in 1918.

Schools and cinemas shut and, despite a little resistance, some churches and chapels did too, in short-lived and partial local lockdowns.

Back in the summer and winter of 1918, miners stricken with flu were being carried out of collieries in the Rhondda and Cynon valleys on stretchers.

Some things have changed. But John Jenkins, the Rhondda's medical officer for health during the year-long flu pandemic, was familiar with disease and the impact of chronic illness.

He also knew about the concept of keeping a distance from infection, especially in tightly packed communities.

Coughing, sneezing - and thanks to coal dust at the time - spitting were known to spread infection. But the limited understanding of viruses meant the concept of hand-washing was not considered important 100 years ago.

Deaths from coronavirus have dramatically slowed down in Rhondda Cynon Taff, with two in the last six weeks

In Rhondda Cynon Taff today, recent infections have been prominent among younger people.

But there are concerns coronavirus will transmit to older and more vulnerable friends, relatives and colleagues.

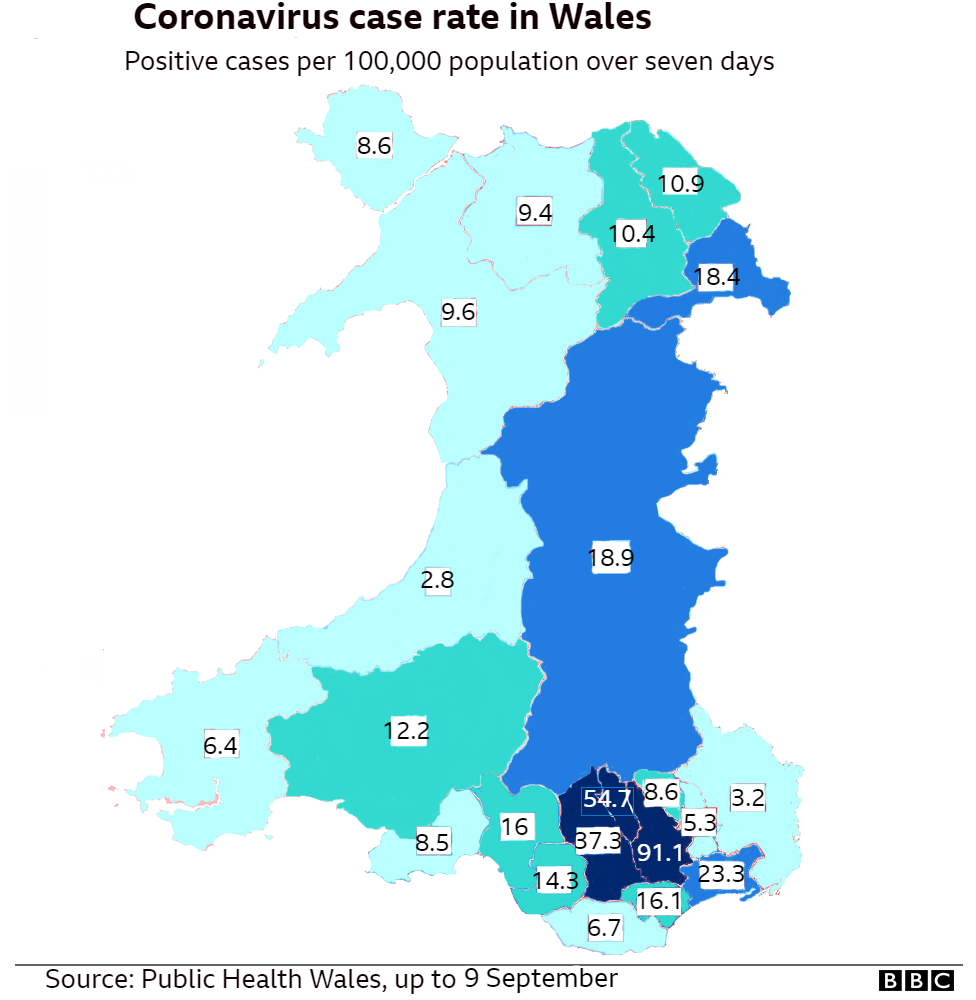

The county already has the highest death rate for Covid-19 in Wales.

And Porth East & Ynyshir and Pontypridd West are the neighbourhoods with the highest number of deaths.

But it is not just about mortality.

Doctors are worried that those recovering from Covid-19 and the damage to their lungs and respiratory systems could face a long road back to health.

The profile of the average patient in critical care in local hospitals with the virus has been male and 55.

And there are concerns about the long-term impact on communities if significant numbers of these patients do not fully recover.

In Rhondda Cynon Taff and neighbouring valleys authorities like Caerphilly and Merthyr Tydfil, there are already disproportionately high levels of people with long-term, poor health.

In harsh economic terms, that increases the social service and health bills in the area and reduces the amount people are likely to earn and spend in the area.

Covid-19 in numbers

2,032total coronavirus cases

41.4 cases per 100,000 in the last week

302deaths, up to 28 August

3.2%proportion of positive tests in last week

A study by academics into Welsh towns found that Porth, one of those areas identified along with Penycraig as having clusters of cases, already has high levels of ill health, well before coronavirus arrived.

Using figures from the 2011 census, researchers found the proportion of people with long-term health problems was 26% higher than average for Wales.

The proportion with bad or very bad health was 43% higher than the Welsh average.

The link between deprivation and being more susceptible to the virus has been well charted so having a job and the wages from that job are relevant.

The same study also found that in Porth there were six times as many people on employment benefits than average for Wales.

In terms of the debate about whether the number of people living together increases rates of coronavirus infection, it is interesting to see the same researchers also found that rates of overcrowded accommodation in Porth were low and broadly in line with the rate across Wales.

Rhondda Cynon Taff still prides itself on its strong communities and the floods earlier this year showed households pulling together to help others.

During the last big pandemic a century ago, it was men underground working cheek by jowl who were infected.

But today the concerns are whether people are at risk from shopping in supermarkets or visiting the pub.

- Published12 August 2020

- Published14 May 2020

- Published11 June 2020