How Spanish flu epidemic devastated Wales in 1918

- Published

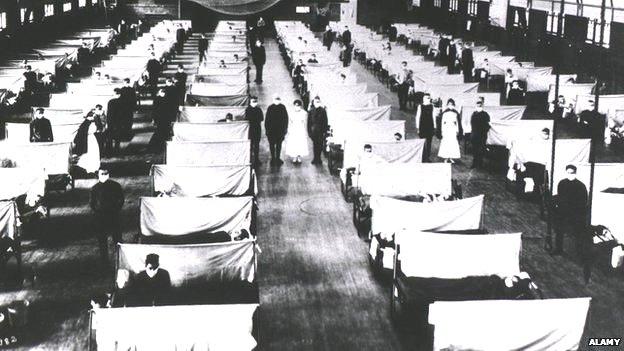

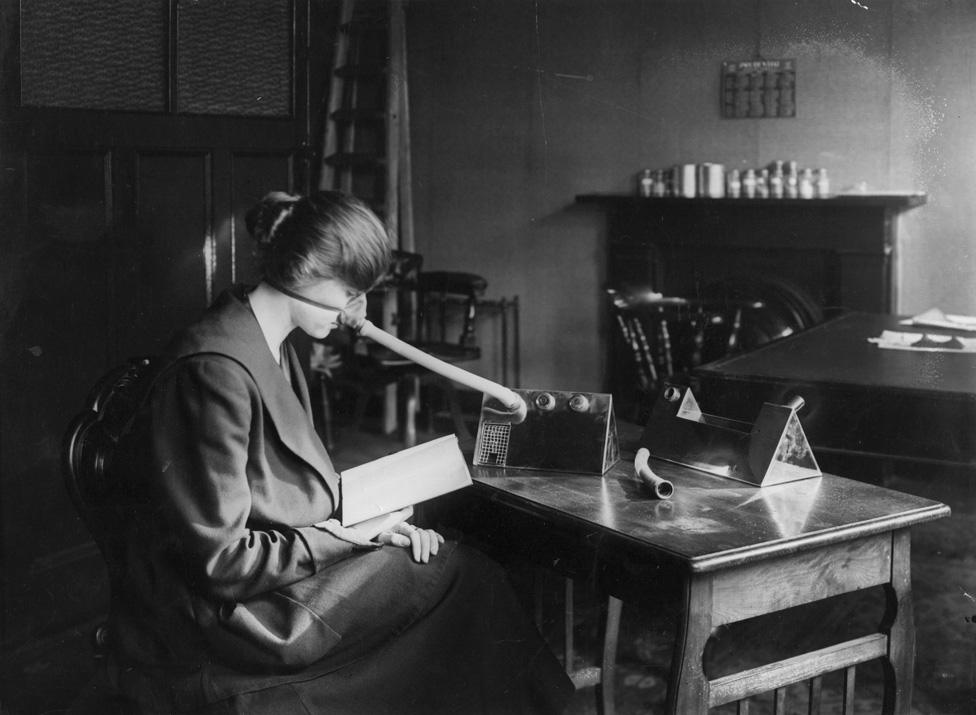

Wearing a mask to help prevent flu - but it was not known then that most infection was spread via the hands

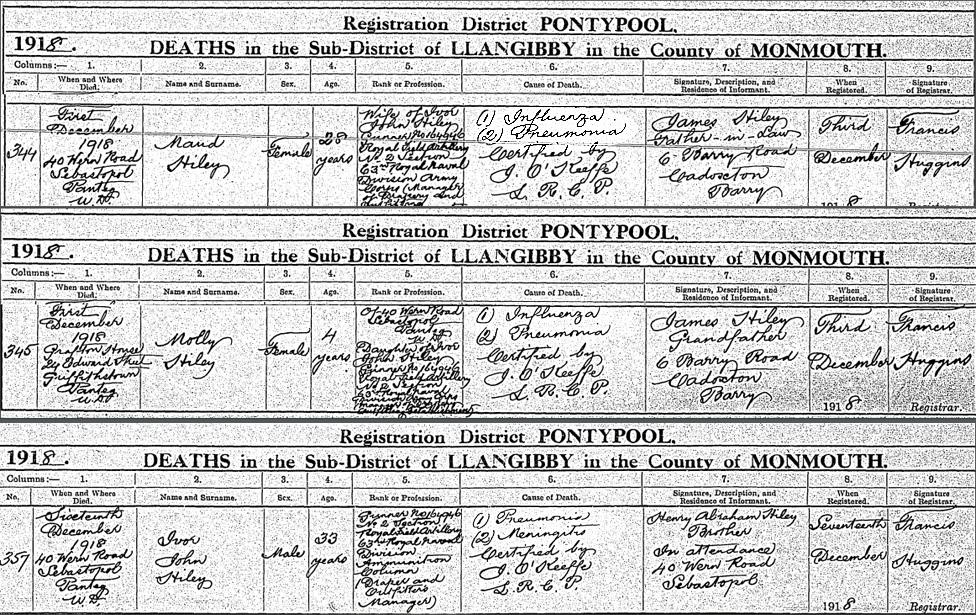

Gunner Ivor John Hiley had survived three years fighting in World War One in France but a month after Armistice Day he was back home - and dying of influenza.

His wife Maud, 28, and five-year-old daughter Molly died two weeks before on the same day, one at home in Sebastopol near Pontypool, the other in a nursing home.

They were victims of a worldwide flu pandemic which in Wales alone would leave an official death toll of at least 8,750 but which is estimated to be as high as 11,400.

Globally, 50m people lost their lives in 1918-19 in what became known as Spanish Flu. It could strike alarmingly quickly, leading to collapse and death within days or even hours. For some, symptoms included lungs with a blue-ish fluid and bleeding from the ears or nose.

World War One played a factor in spreading the disease, as troops moved back and forth between their homes, bases and front line.

Funeral notices of flu victims started to appear next to the names of those killed in action in local newspapers.

But the full impact of the epidemic was missing in a media still consumed by the war, subject to censorship and taken by surprise.

The Hiley family all died of influenza and its complications - death certificates

Ivor Hiley, 32, the son of a butcher from Barry, had managed a drapery business before the war.

He had arrived at Newport railway station, on leave from the Royal Field Artillery, where he had been working in the ammunition supply lines in France. He had walked the eight miles (13km) home by midnight but reportedly by the morning was already showing signs of flu. He died on December 16.

Both Maud and Molly had developed pneumonia while Ivor's complications included meningitis. Maud's brother also died in the outbreak while other family members were infected but survived.

Council-appointed medical officers of health were at the vanguard of dealing with the outbreak on the ground.

According to Monmouthshire medical officer Dr David Rocyn-Jones, the epidemic "spread with alarming rapidity".

Dr Rocyn-Jones - a former doctor and colliery surgeon in Abertillery - said the infection generally attacked men working in the pits, followed by the mothers and older children "and finally the children attending the infant schools".

Daniel Davies, 24, (left), one of many soldiers who died from flu. He was on home leave in Llandeilo; David Evans, Swansea pub landlord and special constable, was taken ill after driving flu patients in an ambulance and later died

But many soldiers died too.

John Williams, 22, was a milkman before he spent nearly three years as a private in the transport section of the South Wales Borderers. He was given leave after contracting flu and came home to Cwmdare. He died the day before the end of the war.

Miner Daniel Davies died two days after the end of the war while on home leave in Llandeilo, another veteran of the Royal Field Artillery.

The Cardiff and Rhondda experience

Most deaths in Wales - as elsewhere - happened in the autumn.

But in Rhondda, an outbreak in July cost 144 lives in the valley.

Influenza was said to be "rampant" in Ferndale, with 1,300 miners laid low, along with 1,000 in Tylorstown.

Sick miners were being carried away on ambulances "just as if there had been a big accident," according to one colliery agent.

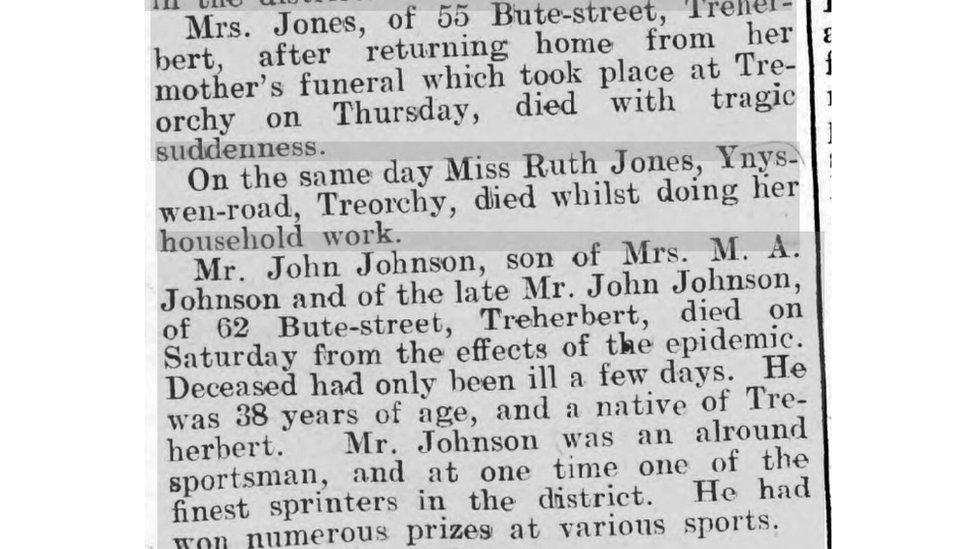

Weekly newspaper columns described sudden flu deaths, while lists of war dead were still being reported

Dr John D Jenkins, the medical officer for health in the Rhondda, wrote:

"Whole households were in many instances struck down and made dependent on the ministrations of neighbours...few families escaped and there was much suffering and sorrow."

Indeed the intimacies of living in mining communities themselves - including being a good neighbour - contributed partly to the spread of the disease, according to Dr Jenkins.

He lamented the "well intentional but ill-advised custom of neighbourly inter-visitation between the occupants of infected and unaffected houses".

There was also the habit of spitting "still prevalent in most communities" - a by-product of working with coal.

The top deck of a bus is sprayed in the hope of reducing infection. Swansea Council ordered ventilation and disinfecting of trams to help stop the spread of flu

FLU FACTFILE

At least 50m and up to 100m may have died worldwide, including 12.5m in India. Civilian deaths in the UK are estimated at 185,000.

Although called Spanish flu, the outbreak is believed to have started in Kansas, United States - picked up from fowl and transferring to a military base.

The genetic characteristics of the virus were identified about 20 years ago.

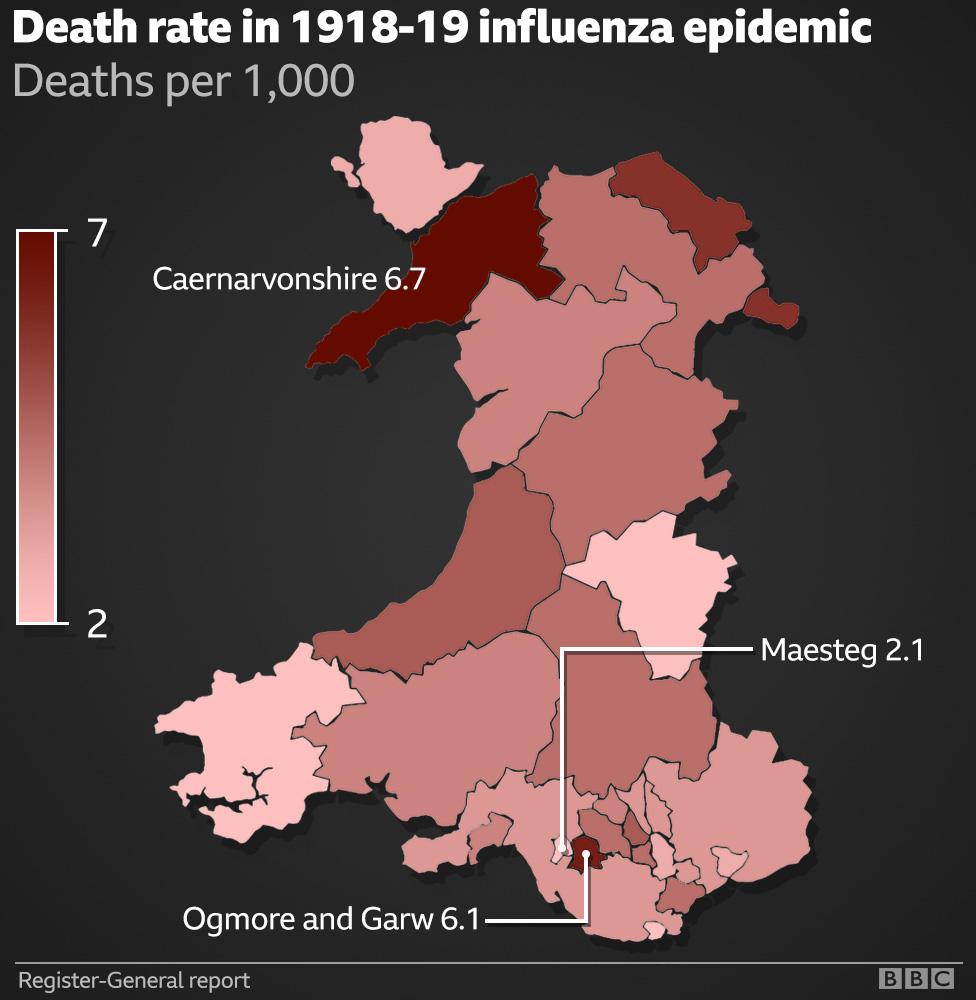

Overall, the death rate from influenza over the year in Wales reported by the Registrar General was calculated at 4.3 deaths per 1,000; it was as high as 6.6 per 1,000 at its peak.

Barnsley (8.3) had the highest mortality of 82 county boroughs in England and Wales, followed by West Bromwich (7.7) and South Shields. Hebburn had the highest mortality of 161 towns, followed by Jarrow and Kidderminster.

In Cardiff, the worst of the epidemic started in October.

Doctors were struggling to cope and some schools were closed. Undertakers were overwhelmed - there was even a shortage of coffins - with 37 funerals on one day in October and Army labour corps drafted in to dig graves. There were reports of bodies being transported in carts from the docks. One man was so delirious with fever, he fell to his death from his bedroom window.

Peculiarly, the epidemic did not affect the very young or very old quite as much. Of the deaths in the city, 44% involved younger adults, aged 25 to 45. Older people are now believed to have gained more immunity from a similar infection during their lifetime.

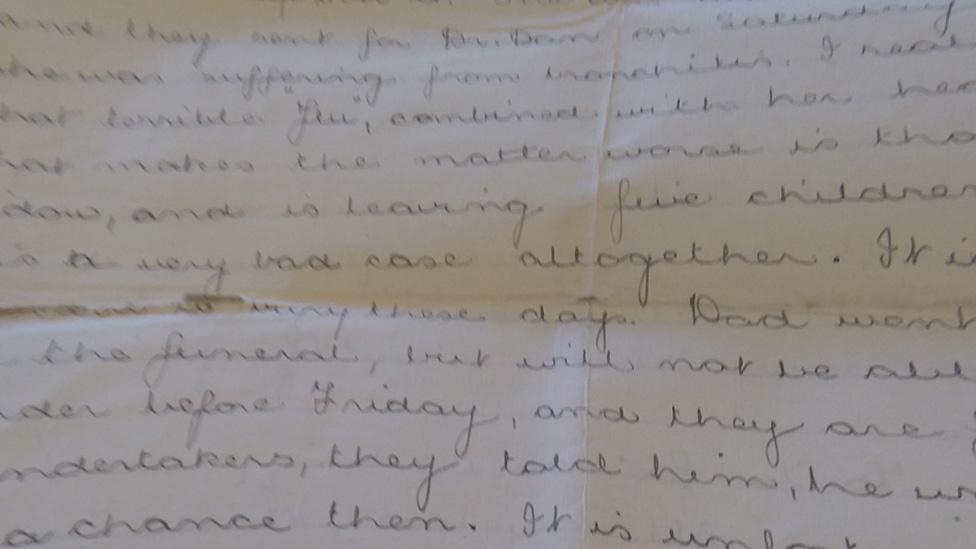

This family letter reports the death of a Cardiff widow, leaving five children

Annie Harding, 44, from Canton, had been widowed for 10 years and had five children.

Already suffering from heart trouble, her death in November at her home in Railway Terrace - acute bronchitis appears on the death certificate - was one of many in the outbreak in the city.

Her brother who lived nearby was at her bedside when she died and was himself feeling "not very grand".

A letter from Annie's niece Sybella to her fiance serving in the Army survives in the Glamorgan Archives. She had no doubt it was the "terrible flu".

"Dad went yesterday to order the funeral but will not be able even to [do that] before Friday and they are full up and at the undertakers they told him he would be lucky if he gets a chance then," she writes.

"There are so many deaths just lately that they were unable to arrange funerals to cope with them".

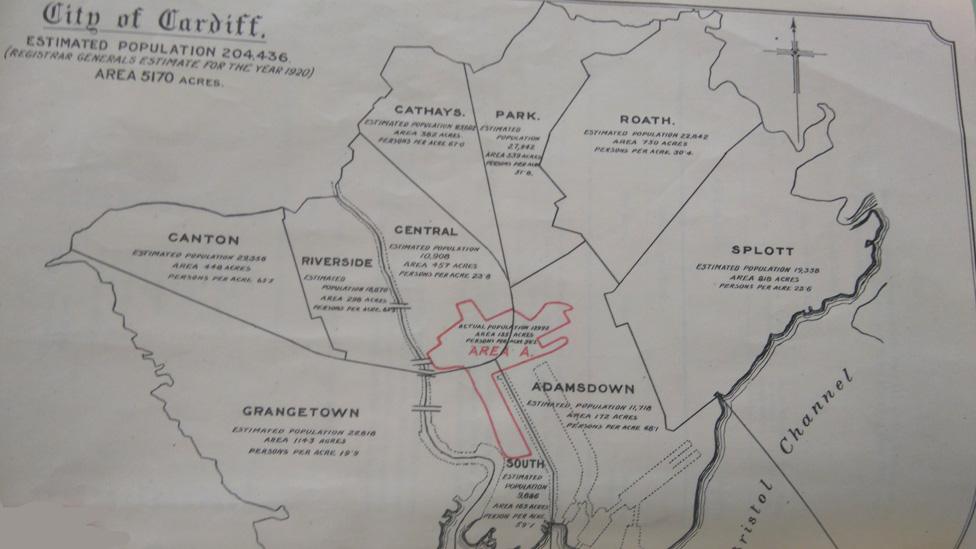

This map produced by Cardiff's medical officer drew attention to overcrowding and poor housing in this period

It appeared worse in the poorer and the more overcrowded parts of Cardiff.

South Cardiff - which included the docks - had the highest death rate - 29.9 per 1,000.

These stories might interest you:

A cartoon depicting the impact of influenza, reflecting the trivial way the epidemic was sometimes treated in the newspapers of the day

Out in the country

Rural areas did not escape and indeed the highest death rate for the epidemic period in Wales was in Caernarvonshire in north west Wales.

In Porthmadog, left with only two doctors due to the war, they were "overwhelmed" with work day and night. In Bangor, two local police officers died, while the infection spread among American servicemen at local camps.

The Garw valley had the highest death rate for a single week during the epidemic in the whole of England and Wales

But the way the flu could have a devastating impact in even the smallest of communities was illustrated in the tight mining communities of the Ogmore and Garw valleys.

In the last week of November, 57 people died. Translated into a death rate, this was the highest anywhere in England and Wales in any single week of the epidemic.

This map of the old counties of Wales shows how the influenza death rate varied

Victims included four members of the same family within four days of each other in neighbouring farms near the village of Llangeinor in the Garw valley.

Martha Richards, 30, died the same day as her father Morgan Rees; her mother died of shock and 'flu complications the day after Martha's husband Thomas also succumbed. A sister would die later that winter.

The Glamorgan Gazette reported "despondency" with many deaths reported and "hundreds laid up".

But other areas escaped comparatively lightly. Maesteg recorded "only" 50 deaths and Wales' lowest death rate at 2.1 per 1,000, and only 78 people died of flu in Barry, the second lowest death rate of anywhere in Wales.

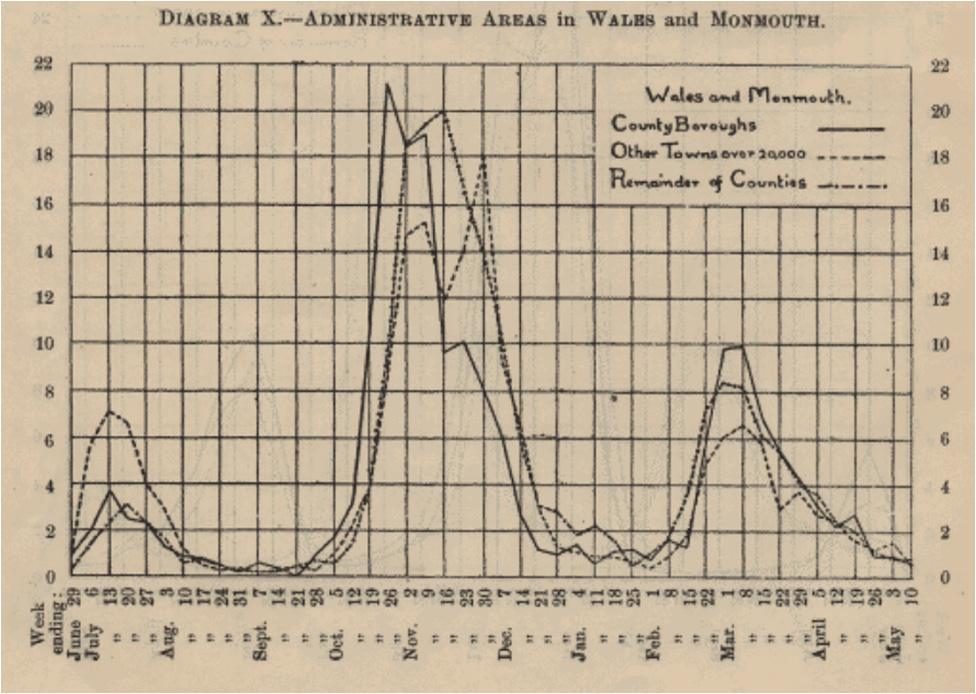

The Registrar-General's graph showing the progress of the epidemic in Wales - especially the most deadly second wave

Could more have been done?

Across Wales, precautionary leaflets were issued. The advice included avoiding sneezing and coughing to spread infection, to boil handkerchiefs, take to bed in a well-ventilated room and to avoid overcrowding or places of entertainment.

This led to school closures and restrictions being placed on some cinemas and theatres.

Epidemiologist Dr Meirion Evans, of Public Health Wales, says the 1918-19 experience "dwarfs things like the bubonic plaque or indeed more recent flu epidemics and pandemics throughout the 20th Century".

The sheer scale of the flu's spread "way beyond the parameters of an normal flu season" and the speed of symptoms acting on a minority of patients would have taken the medical profession by surprise.

"At the time, they didn't realise it was a viral infection," he said.

"The theory current at the time was that it was bacterial infection. It was thought the main ways it spread was simply by respiratory droplets - so if you wore masks it would protect you from it. We've since learnt that actually in practice it probably spreads most efficiently on hands, people cough and sneeze and they get the virus onto their hands."

Epidemics expert Dr Jonathan D Quick said something happened with the virus in its second wave to make it more deadly.

"Two things have to happen for an epidemic like that - you need to have something that's very contagious - a virus that humans have no immunity to," he said. "So it was a totally new virus from the point of view of our immune system, so we were really susceptible."

Dr Evans added: "But obviously things like overcrowding, soldiers in barracks, schoolchildren in dormitories, people going in and out of each other's houses, or looking after people who are sick as opposed to confining them in the bedroom to ensure there was as little direct contact as possible. Those are all factors and features in the spread of flu."

Why did we seem to forget what happened?

Catherine Taylor left behind two young children

Estimates of how many died in Wales go beyond the "official" figure of 8,759, when the numbers who died from related conditions - like Annie Harding - or where influenza was a contributory factor are considered. The final figure is likely to have been at least 11,400.

What was the impact on the many families affected, at a time when they were reeling from war?

Catherine Taylor, from Cardiff, was 29 when she died in October 1918 leaving a daughter Kathleen and young son Thomas, five.

Thomas's daughter Jan said they moved to live with relatives.

"My dad, his sister and my grandfather lived with a maiden aunt," she said. "I don't remember my grandfather a lot but he wasn't full of fun," she said. "I think it was difficult. My father never talked about it. It wasn't easy for any of them.

"Millions of people have never heard about the Spanish 'flu. I only know because my mother told me about it; it's sad but my dad never complained."

Dr Niall Johnson, who has studied the history of the pandemic in detail, suggests reasons which might explain why influenza has slipped from the collective memory.

"These include the fact that it was 'only' flu - particularly when contrasted with the trauma of the war; the common and banal nature of the disease; the low case fatality rate - most people survived; the timing that sees it conflated in the overall war experience, and so on," he said.

"I think all these play a role. Much in life is complex and multi-factorial, rarely is there a single, simple explanation."

- Published15 October 2018

- Published20 September 2018

- Published13 October 2014