Wales alcohol restrictions: Temperance's long history

- Published

Despite the alcohol restriction, Wales is far from being in prohibition

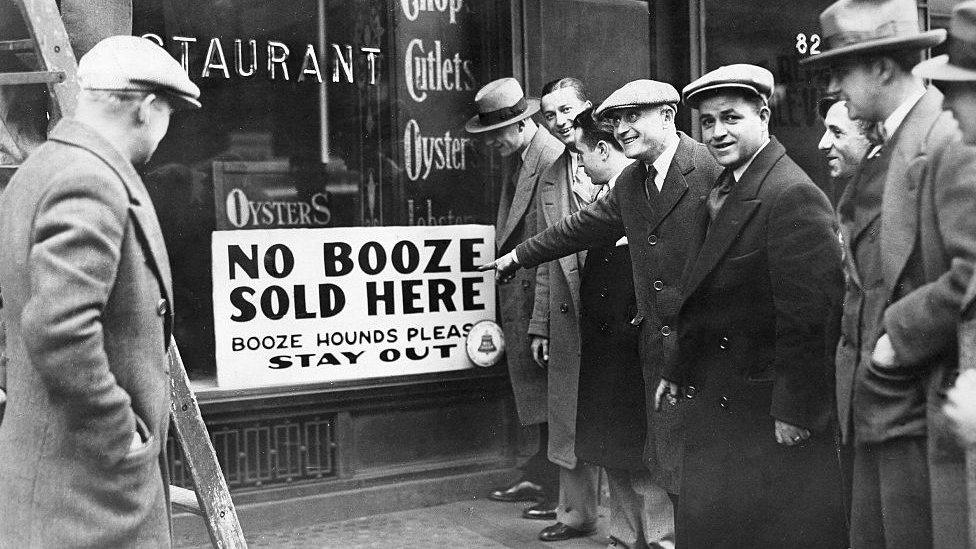

Pubs banned from serving alcohol! Pubs closing at 6pm! We're in the '20s - is this prohibition mark II 100 years on?

Unless you've been living under a rock this week, you'll know that from Friday evening, in bars around Wales the beer taps will be turned off and the doors will close.

That's not the complete end, as bars can still serve takeaway alcohol all day up until 10pm. But there'll be no more Double Dragon in the Dog and Duck. No more goings on after Dark in Cardiff, as the city's traditional pint was praised by musician Frank Hennessy.

But it may come as a surprise to some to learn that abstaining from alcohol has a long history in Wales through the temperance movement.

It came from different areas of society with varying aims and agendas, but broadly all sought to reduce the use and influence of drink on people's lives, especially among the working classes.

Some were driven by religious fervour or moral attitudes to drink, some by health and social concerns, and others by economic worries, particularly employers who feared the effects on their workforce and its productivity.

Did temperance movements want to ban alcohol?

It may surprise you to learn temperance campaigners did not start out by aiming to bar people from drinking altogether. Many early advocates recommended abstaining from distilled, high alcohol content spirits but were more relaxed about the use of beer and wine.

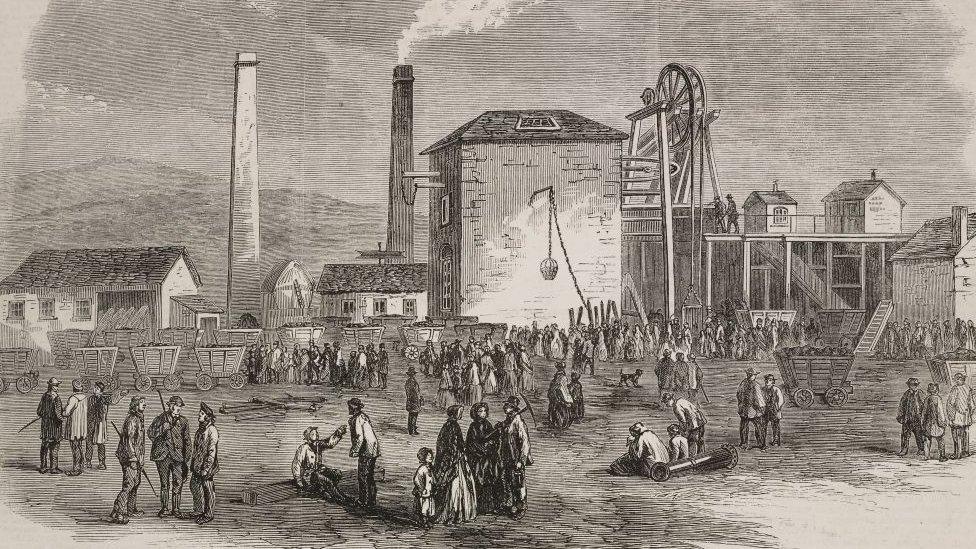

Morfa Colliery in Swansea was one example of the changing industrial face of Wales

For centuries, ordinary people in Wales and beyond had routinely drunk beer as part of their daily lives. For one thing, brewed beverages were safer than untreated water, killing germs and parasites, and it was cheaper than tea, which was another method of safe drinking.

But the movement from an agrarian towards an industrialised workforce in the late 18th and early 19th Century helped bring changes to how alcohol was both used and viewed.

Wales was at the coalface (literally) of the industrial revolution. Its black gold from the south Wales valleys powered the world for generations and provided the fuel for iron and steel production, transforming previously rural areas.

Communities of working men sprung up in these areas, and the pub became a focal point for a bit of relief after gruelling 12 to 14 hour shifts down mines or in factories.

Alcohol consumption was rising as the 19th Century wore on, helped by the passing of the 1830 Beerhouse Act, which meant any ratepayer who could afford two guineas per year for a licence (about £145 today) could brew and sell beer or cider from their home or premises.

The craze for gin in the 18th Century had led many to view beer as a far more acceptable, weaker alternative for those who drank and the act was viewed by legislators of the time as a way of increasing competition with inns and alehouses and promoting the use of beer rather than spirits.

Naturally, this led to a large rise in the number of places beer was available for sale - by 1841, 45,500 licences had been issued across the UK, and the beerhouses were accused of promoting drunkenness, contrary to the initial intent.

A street meeting extols the virtues of temperance

There had always been temperance voices raised in the UK but it is generally accepted that the rise of the movement in the USA in the early years of the 19th Century was a significant factor in its spread in the UK.

The first temperance society in the UK was set up in 1829 in Scotland, and Wales was not far behind. There were 25 across Wales by 1835.

At the same time, the Chartist movement - the struggle for working men to get the vote - was active and had many adherents particularly among the new industrialised communities of the Valleys and urban centres like Newport, site of the fatal Chartist uprising in 1839.

There was a "temperance chartism" which promoted moderation in drinking, seeing it as a way of proving to the upper classes that working people could be responsible and trusted with the vote.

And that desire for respectability was heightened following a 1847 review of the state of education and society in Wales.

It led to the publication of a report which became known as the Treachery of the Blue Books, and portrayed the Welsh as essentially amoral, heaping blame on the Welsh language and religious traditions.

What was the role of religion?

Wales had long been a land of the nonconformists, with the chapels dominating the religious and cultural landscape, and heavily linked to the Welsh language itself.

In the first half of the 19th Century, a new chapel opened every eight days. The Anglican church in Wales was overshadowed by Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians and Congregationalists, with 350,000 registered members as well as less formal worshippers who attended but were not officially recorded.

Temperance was particularly linked to the Methodist tradition, which saw social issues such as poverty and violence in the home as exacerbated by drunkenness. Many Methodists were advocates of total abstinence and this tendency grew stronger as the 19th Century advanced.

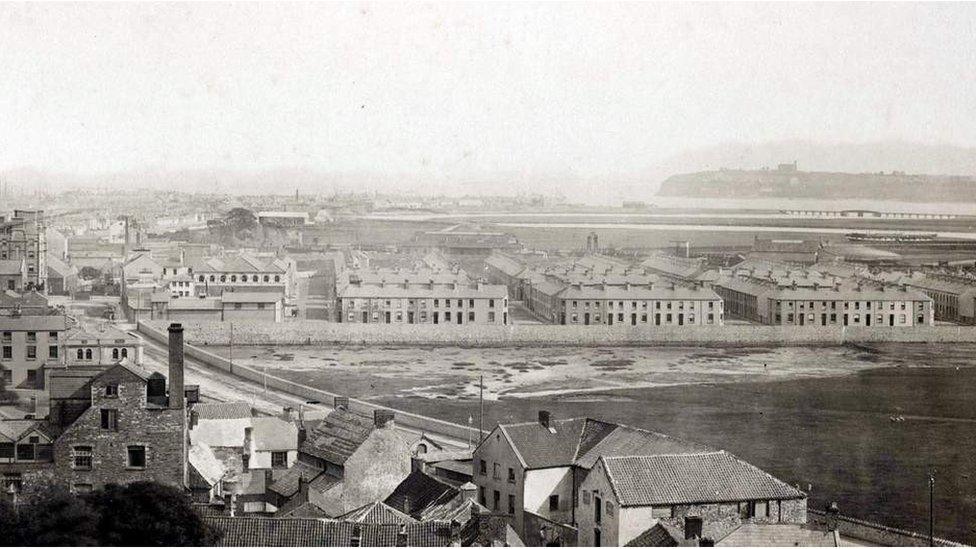

Temperance Town in Cardiff

An area of central Cardiff built in 1860 became known as Temperance Town because its owner, Colonel Edward Wood, did not approve of drink and specified no occupation involving alcohol could be pursued there.

These strands in Welsh society led to the passing of one of the first ever Wales-only acts of Parliament, the Sunday Closing Act of 1881, shutting pubs entirely for the Sabbath, decades before coronavirus came along and achieved a similar end.

Not everyone was keen to see the pubs shut on Sunday, of course - at the time it was many working people's only day off.

Illegal drinking clubs sprang up predominantly in the south Wales towns, originally "shebeens" where individuals would sell beer from their homes, before being closed down by police when discovered.

But as Swansea University PhD student Rory Clark explained in his studies of the period, there was a phenomenon which became known as the Hotel de Marl, where a group of Cardiff men found a way around the law.

He told BBC Wales: "A group of Grangetown residents realised that they could class their gatherings as an official working men's club with the Marl pits [clay pits on Ferry Road] as their meeting place.

"Private clubs were allowed to provide their members with 'refreshments' on Sunday, so these men reasoned that if the patrons were 'members' who paid a 'subscription' [money tossed on the floor] it would not count as a transaction and therefore they could drink as much as they liked."

Local magistrates ruled it legal, but eventually the landowner, Lord Windsor, shut the area and the original Hotel de Marl came to an end.

However the idea had caught on and many a "Hotel de Marl" was reported between 1890 and 1900 across the region.

What was the role of women?

Women were often at the forefront of the temperance movement

Women, who often suffered from the effects of their menfolk drinking excessively, whether in depriving the family of money to feed itself or from alcohol-related violence, were a significant voice within the temperance movement.

Lady Llanover, the heiress to the Llanover estate near Abergavenny, motivated by her Calvinistic Methodist faith, was so convinced of the importance of temperance that she closed all the pubs on her land, replacing them in some cases with alcohol-free temperance bars.

Towards the end of the century, the North Wales Women's Temperance Union was established in Blaenau Ffestiniog and established branches all over the north.

This was followed in 1901 by the Women's Temperance Union in south Wales, established by the bardic poet Cranogwen, Sarah Jane Rees, who was particularly concerned with violence against women caused by drinking.

Did the ideas of temperance last?

As the 20th Century advanced, World War One seemingly gave temperance ideas a welcome boost through the Defence of the Realm Act 1914, which shut pubs early and watered down the beer.

But the great social changes wrought by the conflict and its aftermath led to rapid decline in religious observance in Wales, and with it the star of the temperance movement waned.

It's probably fair to say its ideas have not endured. In 2019, 18% of Welsh adults were classed as either harmful or hazardous drinkers.

Now that is a sobering statistic.

- Published9 January 2019

- Published1 December 2020

- Published1 December 2020

- Published30 November 2020

- Published1 December 2020

- Published2 December 2020