It's A Sin and HIV in the 1980s: 'By 25, I'd lost 50 friends to Aids'

- Published

Russell T Davies' series It's A Sin helped Channel 4's streaming service to a record-breaking month

"By the time I was 25, I had lost 50 friends to Aids and I stopped counting at that point."

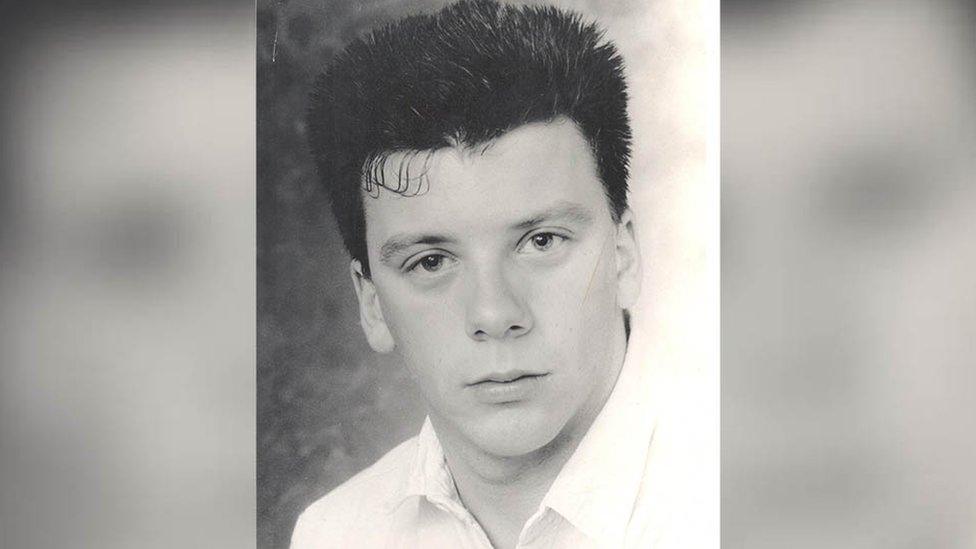

Mike Phillips, 53, was a young gay man in the 1980s and, like many others who have watched Russell T Davies' Channel 4 series It's a Sin, he has been reflecting on the HIV and Aids crisis it depicts.

The programme has shone a light on the misunderstandings and the mistreatment of many gay men at the time.

"I am still processing it now, those things that Russell writes about, there is truth in it," Mike said.

He was told he was HIV positive in 1991 and, at just 23, he saw it as a death sentence.

'Seeing someone die at 27 was profound'

"It was just a real shock, you know, being told you have possibly only got six months left to live, I just didn't know what to think. One of my best friends insisted on coming with me and we were both just stunned when I got my result. I am just so glad she came with me."

Mike was in drama school in Cardiff at the time but his life was "turned upside down" by the diagnosis and in the months that followed he left, abandoning his plans of a career in acting.

"I just thought it is difficult enough being out and gay in the industry, but being HIV positive as well, well it just isn't going to happen," he said.

Mike Phillips (second from the right on the second row) was a member of West Glamorgan Youth Theatre - as was Russell T Davies and Hollywood star Michael Sheen, who is in the front row

Mike, who was openly gay and had no plans to hide his sexuality, said he had to go to London, to an organisation called Body Positive, to find support and contact with people in his position.

"That was a real great support for me, but what is awful is knowing not many of my peers from that group are still around today," he said.

Mike felt there was a need for a group like that in Cardiff and decided to set one up with his friend Martin Nowaszek, who was HIV positive.

But not long after, Martin became ill.

Mike joined Martin's sister, her husband and a handful of his closest friends in round-the-clock shifts at his bedside in the final weeks of his life. He died aged 27.

Mike Phillips said there was a "funeral every week" at one point

"Seeing someone of that age die in front of you was just profound - it was a huge privilege but profoundly painful."

Mike said there was "always this uncertainty of who is going to go next" and there was a period with a "funeral every week" in his tightly knit community.

But Mike, who was alienated from his family, said his friends got him through and he could see parallels with some of the characters in It's A Sin.

"I had a lot of 'Jills' - Lindsey who came with me to get my HIV positive test result, we're still friends, she calls me little bro and I call her big sis. My friend Cath who came back from Cheltenham to support me, I call her my soul sis," he said.

Jill Nalder's story is the inspiration behind hit TV show It's A Sin, penned by friend Russell T Davies

In the UK, 106,000 people are currently living with HIV, with 98% of those on treatment.

Mike feels a memorial for those who have died as a result of HIV and Aids is long overdue.

'Everyone was terrified'

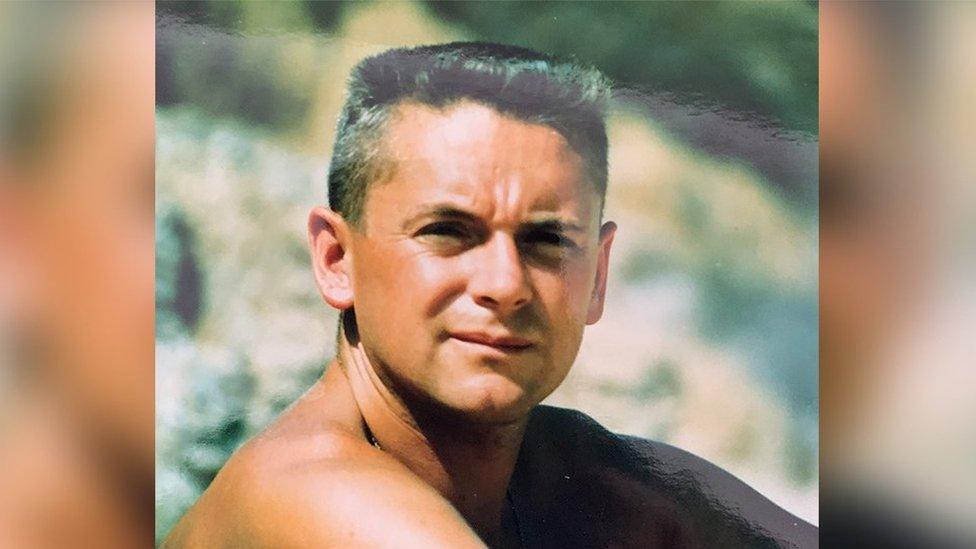

Nigel Lewis remembers whispers about Aids from the United States and then in London. He came out when he was 19 but did not tell his family until he was 27.

"It was called this 'gay plague' but no-one knew how it was spreading. Was it contagious? Everyone in the gay community was terrified, and all of a sudden everyone withdrew.

"I can remember how all the pubs went quiet and emptied and some people avoided you due to ignorance. You could see they were embarrassed to talk to you. It was a very unkind time."

Nigel Lewis recalls good times but also a lot of challenges

The 63-year-old recalls sitting next to a close friend in a clinic who, when Nigel asked him if he was OK, replied "no, I have HIV".

"He died not long after and I watched him keep it a secret and not tell anyone, it was terrible.

"That was the other thing, the shame that the men had who had it. It was heartbreaking, I knew one lad really well, he ended up going into hospital and, because he was so ashamed, he wouldn't let anyone see him, so no-one cared for him. It was just horrible, so upsetting."

Nigel said there were also good times but it was a fearful period.

"You didn't even dare tell anyone you were gay, let alone your HIV status. It was a really worrying time."

A scene in It's A Sin shows one character scrubbing a mug until it breaks.

It brought back memories of Nigel's fears about his colleagues using his cup or spoon and that they might be worried they would catch Aids.

Nigel said his friends and family stuck by him when he came out, but there were still challenges.

"I had good friends, but we still had to fight all the ignorance, you would be fearful of wearing a red ribbon on World Aids Day and getting on the bus thinking you were going to get attacked."

Nigel was the victim of a homophobic attack in a club

Nigel even suffered a homophobic attack on what he describes as "probably the worst day of his life".

He was punched several times, leaving his face "unrecognisable". He lost his confidence and did not go to work, finding it hard to speak to even his closest friends for some time.

'A pretty bleak time'

Craig Stephenson lived in Barry in the 80s and struggled to come to terms with being gay. But when an opportunity to work in London for a year in 1986 came up, it allowed him the space to come to terms with his sexuality.

"It was a difficult time, under Margaret Thatcher's government and Clause 28 was happening, they were trying to stop local authorities promoting homosexuality as a way of life.

"There was so much negativity around being gay and, at the same time, there was this kind of double whammy, this new disease that was ripping through the gay community," he said.

The 57-year-old said it was not a pleasant time to be even thinking about coming out because of the negativity.

"You just had this feeling you were going to be ostracised and it basically took me a lot longer to come out than it probably should have. So I was in my mid-20s when I moved back to Barry and I still hadn't come out properly."

In 1989, he moved to Cardiff and felt he could be more open about his sexuality, but he felt you still had to be careful about who you told as there was a lot of homophobia.

On top of this, Craig said the HIV epidemic cast a shadow over the gay community.

"You knew people who were HIV positive or who had Aids and then you gradually no longer saw them, I had two friends who died of Aids.

He added: "It was a pretty bleak time for gay people, people were losing friends, which emotionally hits you, it just felt like such a dark time. The adverts, bringing the only information available were so horrifying and scary.

"It just wasn't a pleasant time at all. There was a lot of denial. People thought it was a choice to be gay and this disease they brought on themselves, people didn't understand it was an orientation and not a lifestyle choice."

Craig said it was more prominent in other areas like London, but it did have an impact in smaller cities and towns.

"There were people you know of who had died, even if you didn't know them personally you knew of them, because in Cardiff the gay community was quite a small, close-knit community."

'I had so much shame and guilt'

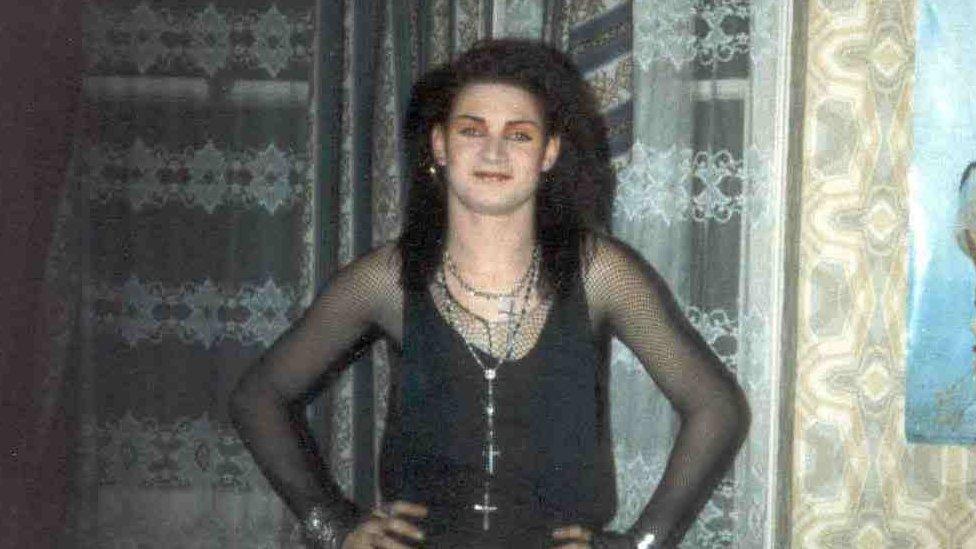

Garry Brough grew up in Rhondda and left to go to London for college when he was 18 in 1985.

He knew about HIV as it was in the news, and it was also the year that testing was first made available. Garry felt it made sense to get tested, and went every year.

He was negative, up until 1991.

"The test came back positive, and I just wasn't expecting it," he said. "I wasn't prepared for what that meant."

Garry Brough said he struggled to cope after a positive HIV test

Asking the doctor, he was told as he was negative last year, it was a new infection so he would have a couple of years of good health, then his health would start to fail and he was expected to be dead in five years.

He was 23, in his final year at college about to finish his degree.

Garry knew he was gay from a young age, but bullying led him to have a lot of internalised homophobia and he turned to drink to suppress those feelings.

"I had so much shame and guilt and just had an inability to cope with it and to manage it. I had a few close friends who were incredibly supportive and my parents were cautiously supportive.

"I remember them saying 'we want you to be happy but be careful of Aids' - that was one of the first things they said to me.

"And at that point, if you were a gay man, you were just expected to get Aids, you didn't really know what being careful meant, there wasn't any clear information," he said.

Garry said he remembers thinking "I am going to be dead before I am 30" and it was "a huge wake-up call".

He refused the medication recommended by his doctor as he wanted to avoid the potential side-effects of the trial drug - the only one available at the time - and opted for alternative ideas.

"Having given up alcohol and drugs, I then gave up caffeine and sugar and dairy and meat. I was doing tinctures of this and juices of that and in some sense it gave me some sense that I was in control when in fact I really had no control," he said.

Garry Brough, Mike Phillips, Nigel Lewis and Craig Stephenson as they are in 2021

Refusing treatment for so long, Garry developed Kaposi's sarcoma - a type of cancer caused by a virus. A key cell count was low and he was diagnosed with Aids. He then started chemotherapy.

By 1996, there was evidence that a combination of drugs was working and Garry started treatment on his 30th birthday.

"Seeing people getting out of their death beds, being told to visit friends in hospital as they aren't expected to be around next week, and then next week they are in the club, it sounds dramatic but that is what happened."

One thing he struggled with was accepting he was going to live and Garry said it took time to come to terms with that.

"The fear of what life would be and could be like, not knowing what was going to happen and expecting ongoing illness, that was far more terrifying and took me a long time to come to terms with."

It was at this point that Garry started volunteering and got involved in HIV peer support.

He felt that is what got him through and he has continued to focus on it for the past 20 years.

Related topics

- Published5 February 2021

- Published3 November 2019

- Published1 December 2016