Nuclear test veterans: 'My dad was treated like a guinea pig'

- Published

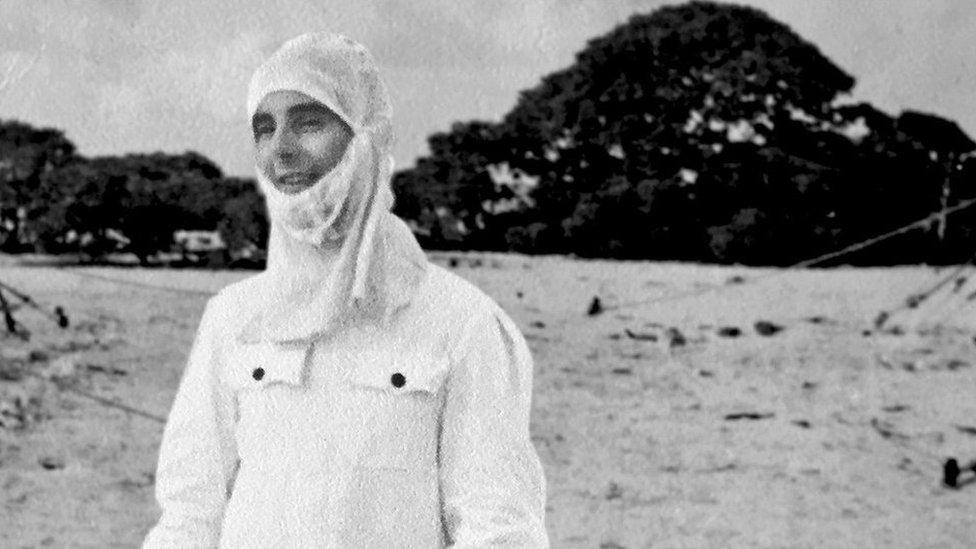

David Purse saw the operation as an adventure in an exotic and sunny climate

When David Purse was sent to Australia, he thought it would be a "wild adventure" in a little-explored place.

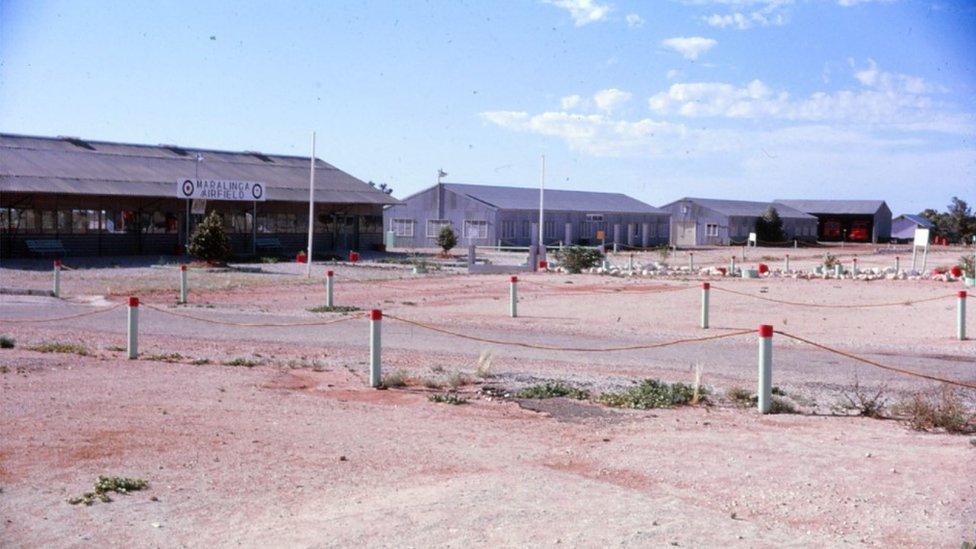

However, the RAF flight lieutenant's posting to a remote area called Maralinga was to test atomic weapons.

Son Steve, 47, from Prestatyn in Denbighshire, puts his own "unique" condition down to "a rare genetic mutation" caused by radiation.

The Ministry of Defence said three large studies found no link between the tests and ill health.

But a study at Brunel University is currently looking at the possibility genetic damage from the tests, external has affected the children of personnel.

"Flying through mushroom clouds or watching", Steve believes men were "treated like guinea pigs" and wants recognition for them, adding: "It wasn't an act of God but an act of government."

In all, about 40,000 British personnel took part in the testing of atomic and hydrogen bombs in the 1950s and 1960s.

Most were in the Pacific - the biggest being Operation Grapple, where about 22,000 people oversaw the exploding of bombs in 1957.

Maralinga, in South Australia, saw the first test launches of atomic weapons from aircraft in 1962.

The Cold War saw the testing of nuclear weapons around the world, including here in the United States

"He was told at short notice and was looking forward to visiting a warm country, a relatively unexplained place, and having a wild adventure," Steve said of his father.

However, he was "close enough to ground zero to see sand to turn to glass" during tests, with no protective equipment.

Steve added: "There was a rope saying 'do not enter' but radiation was in the sand and would blow into food, into their face.

"They would swim in the lagoon, and catch fish that contained highly toxic radiation."

Steve Purse - who is an actor - is unable to walk far without crutches

His father died with Alzheimer's disease, but doctors said his skin showed "the level of damage they would expect from someone who had spent most of their life in the sun".

It is his own condition, though, that has caused Steve most contemplation, adding: "It was obvious when I was born something was not right. I was visibly disabled.

"Dad had little contact with the RAF after he left.

"It was only years later, a friend wrote and said 'do you know the amount of children of service personnel who have had problems?'"

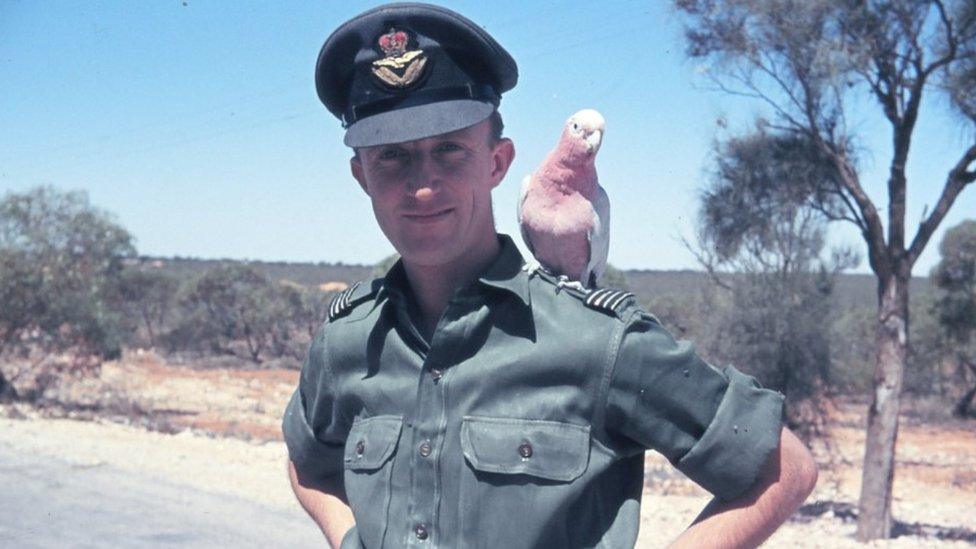

David Purse did not mention being present at tests to his family until years later when they appeared on a television programme

Steve describes his condition as "unique", with doctors unable to diagnose it exactly, but says it is a form of short stature, similar to that of actor Warwick Davis.

He believes it is because of a "rare genetic mutation" as a result of the nuclear tests, and part of the "roulette" future generations must live with.

Steve is worried his baby son, Sascha, could also develop problems as he grows older.

"That's the sad thing, it probably won't die with veterans," he said.

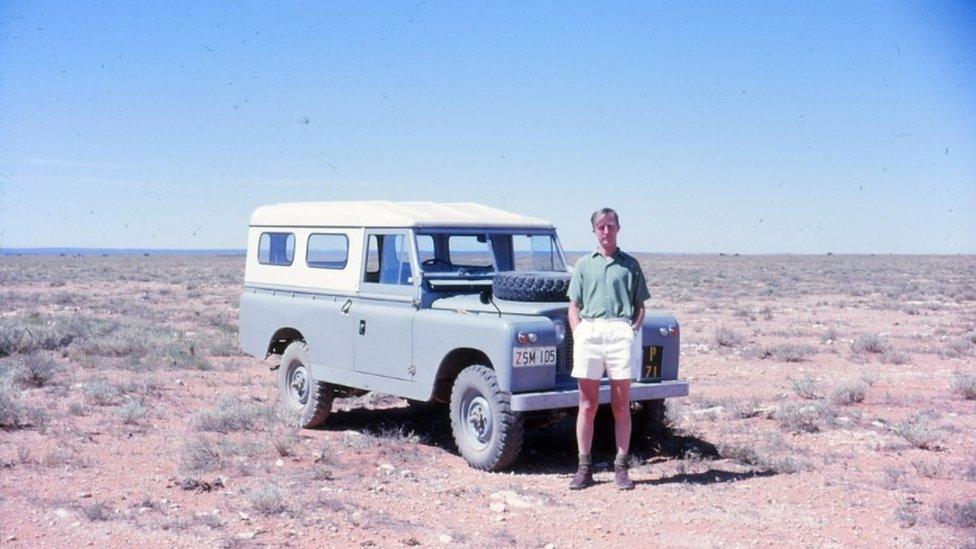

The area was handed back to the Aboriginal people in 1985, with a clean up of the site taking place in 1995

"It was so we could join the nuclear arms race, produce a deterrent to keep us safe.

"There has never been a nuclear war, so we owe them a huge debt of gratitude."

He believes the UK government has constantly turned "a blind eye", adding: "A medal is only a small bit of tin, but it's recognition they were there and did an important job that continues to keep the country safe decades later."

The possibility that children of personnel could be affected was first raised in a study at New Zealand's Massey University in 2007.

Tests on the triggering mechanisms of weapons were also conducted at Maralinga

Al Rowlands, who led the investigation at the university, said results were "unequivocal" that veterans had suffered, external genetic damage as a result of radiation.

Support group Labrats, external estimates there are 200,000 descendants of those who took part in British tests - and says the UK is the only nuclear state not to properly recognise its veterans and support them.

It conducted a health survey with 123 people who took part in tests, external, 76 from the UK.

"Many [problems experienced by descendants] tend to be autoimmune diseases, but if there are problems, they tend to be severe," said founder Alan Owen.

"There are bone problems, teeth problems, eye sight. Issues that are meant to affect one in 1,000 - we talked to 10 descendants, four were affected.

"They have developed cancer, heart problems, a wide range of diseases."

He described talking to veterans about their fears, adding: "When a grandchild is born, they don't ask if it's a boy or a girl, but if it's okay. It's quite sad they're living with that now."

Maralinga was one of a number of sites where British personnel were involved in nuclear testing

Mr Owen's father was involved at Operation Dominic, where the United States conducted 31 tests in the Pacific in 1962.

The American government has paid compensation to British personnel present and Mr Owen wants recognition by UK authorities.

He believes there are about 1,500 British nuclear veterans still alive, adding: "All they want is for the government to say 'we did wrong, it was the 1950s'.

"No prime minister has ever met nuclear veterans. Anthony Eden was warned about the consequences and his reply was 'it's a pity but we can't help it'.

"They have been denied a medal in recognition of their service."

The testing and development of nuclear weapons remains a controversial topic

The UK government thanked those whose efforts "ultimately, kept Britain safe for decades".

"While it falls outside the criteria for medallic recognition, this in no way diminishes the contribution of those service personnel who witnessed the UK's nuclear tests," a spokeswoman added.

A number of veterans have already called for an apology, linking their cancer to the testing.

The Ministry of Defence responded by saying: "The National Radiological Protection Board has carried out three large studies of nuclear test veterans and found no valid evidence to link participation in these tests to ill health."

The Brunel University study has been carried out with those involved in British nuclear tests and their children, external, with results due soon.

"We anticipate that our findings will have a lasting benefit for the broader nuclear community by providing scientific evidence that will resolve current uncertainties and speculation about potential adverse health effects in nuclear test veterans and their families," said chief investigator Rhona Anderson.

- Published16 February 2018

- Published18 June 2018