Afghanistan: RAF veteran recalls lives saved to stop own 'dark spiral'

- Published

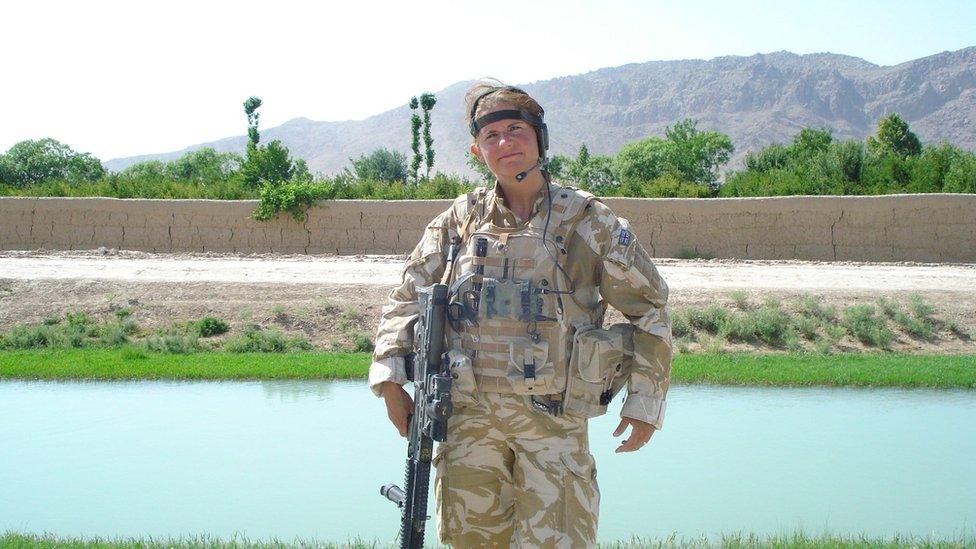

Michelle Partington now helps other veterans to cope with PTSD

A former paramedic diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder after serving in Afghanistan says she is trying to focus on the lives she helped to save.

Michelle Partington was the first female paramedic with the RAF to be deployed to the conflict in 2009.

She said she was devastated by the current crisis and was trying not to focus on it as it could be detrimental to her recovery.

"I was in such a dark place I can't afford to go back there," she said.

The last UK plane flying people out of Kabul took off last Saturday, with the US following on days later to stick to the 31 August deadline pledged by US President Joe Biden.

On Tuesday, UK Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab said more than 17,000 people had been evacuated by the UK from Afghanistan so far, including more than 5,000 UK nationals.

But it is feared hundreds eligible for relocation were left behind after the Taliban took control.

Meanwhile, calls to veterans' charity Combat Stress have doubled since the Taliban took control of Afghanistan, as ex-service personnel seek mental health support.

Some veterans have said they are questioning their sacrifice made in Afghanistan, while others say their efforts were not in vain.

Ms Partington said she had treated insurgents who had come on to her helicopter with live grenades on them

Ms Partington, a former Flight Lieutenant who joined the RAF in 1991 after seeing a stall at a careers fair, has worked with many interpreters in Afghanistan and said she had been unable to check if they had made it to safety.

"It would break my heart if I knew they were stuck there," she said. "Some of them wouldn't acknowledge me because I was a female, others used me to help their kids and wives."

The 49-year-old, who was medically discharged from the RAF after 23 years of service and three tours of Afghanistan, said she had tried to avoid coverage of the current crisis as it could be damaging to her recovery.

"At the worst part of it, I was having panic attacks, nightmares, I wasn't leaving the house, and I was having suicidal thoughts," said Ms Partington, who used to live in Preston, Lancashire, but now lives in Abergele, Conwy county.

Ms Partington said they would give sweets to children who would come and see them in the villages where she was treating residents

She helped save the lives of civilians, colleagues and insurgents, treating people who'd had their legs blown off or who had shrapnel embedded in them, from the military helicopter.

The helicopter was drafted into conflict zones, where they were shot at while picking people up.

"It was horrific," she said.

Back in the UK, Ms Partington said she had to quit her job as a paramedic for the NHS in the north-west of England, because waiting to see what call she was going to be sent out on next was triggering her PTSD.

She said that while she was working for 111 in the triage clinic it was hard to deal with people calling for an ambulance who did not need it, including for a dislocated finger.

"You get some really random calls, some people call because they are lonely, and I understand that," she said.

But she added: "I have seen people with their legs blown off... someone phoned me at 11 o'clock at night because they had burnt their mouth on a pizza.

"Some people phone pretending they have an emergency, because they think if they get an ambulance they will be seen quicker at A&E, but that doesn't work."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Last bank holiday weekend the Welsh Ambulance Service warned non-urgent 999 calls were taking up valuable resources, with people calling for paramedics after losing a toenail and gashing their shin.

"My tolerance was really low," said Ms Partington.

Ms Partington said her hearing had become acute due to having to focus on all the different noises while in the helicopter and she now struggled in certain situations

Ms Partington, who now helps people with mental health issues, said she still lived with anxiety attacks, struggled to be in crowded places, and was triggered by some noises, like helicopters and fire alarms.

"It completely transformed my life, I still cannot work a full week," she said, "but not every day is a bad day."

She said she had since met up with former soldiers she had treated in the helicopter, including Paralympians, and she felt embarrassed when their families thanked her for saving their children.

"It is hard, there are a lot who had injuries and lives that are going to be changed, some people that we saved did not want to live, they said 'do not let me live like this'. To know they realise they still have a life, is amazing," she said.

Ms Partington said she had spoken to other veterans about Afghanistan

She said, while it was not surprising that the area had fallen back under the Taliban's control, it was shocking to see the speed at which it had happened.

"[The women] had about 20 years of relative freedom, to be who they wanted to be, to go to school and work, and now they are going to go back, it's really, really sad," she said.

While some veterans and families who have lost loved ones during tours of Afghanistan have spoken of their anger, Ms Partington, said she had to focus on the good things she and her colleagues had achieved during their tours, rather than the crisis.

"We saved so many lives, and it's people that wouldn't have necessarily survived if we didn't have medical expertise out on the ground," she said.

"I think if I get too involved in what's happening now it could be detrimental to my own personal recovery. If I focus on the problems, I could go into a dark spiral."

If you have been affected by issues raised in this story, sources of support are available via the BBC Action Line.

- Published26 August 2021

- Published19 August 2021