'Mam fled civil war in Nigeria as a child 55 years ago'

- Published

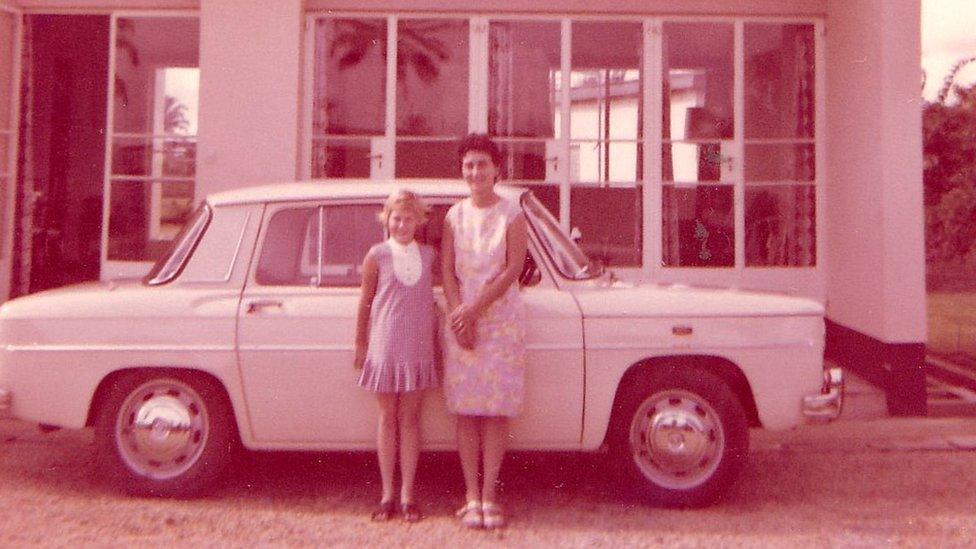

This is the only photograph Gaynor has of her extended family in Nigeria

Fifty-five years ago, Nigeria was locked in a bitter four-year civil war.

It would leave over three million people dead, including over a million starved to death in a blockade of the Biafran south-east.

Many foreign nationals working on Nigeria's oilfields were also caught up in the fighting, including Gaynor Prior, the mother of reporter Neil Prior.

It's Sunday afternoon. After a roast dinner at my mother's home in Swansea, talk turns to our childhoods.

Mam, who's usually quite gregarious, suddenly becomes very withdrawn. "It's 55 years since I left Nigeria," she says.

I've always known Mam had to flee Nigeria as a ten-year-old in the wake of the 1966 Biafran Coup, but it wasn't something we talked about.

Don't get me wrong, she often reminisces about the four highly enjoyable years she spent living in Port Harcourt, but rarely touches on the last few days when she had to abandon all her friends, belongings and her African bush dog, Nero.

I ask her if she'd like to talk about it. I meant as a son rather than a journalist, but to my amazement, she says: "Yes, I want people to read about what it's like, if only so they can better understand what these poor poor Afghani people will be going through right now."

Gaynor enjoyed an "idyllic" childhood in Port Harcourt

Mam's father, Alan Maggs, was a chemical engineer for British Petroleum (BP). In 1962, just two years after Nigerian independence, he was posted to the newly discovered oilfields of the Niger Delta.

My family - my grandparents and their six-year old daughter Gaynor, my mother - arrived in Port Harcourt that year. Mam's elder sister, my Aunty Susan, remained in Swansea to complete her O-Levels.

They lived alongside the Igbo people of south-east Nigeria, an area known as Biafra, which was predominantly Christian.

The civil war was portrayed in the press as a religious conflict, but many other factors were at play, including oil revenues and historical tensions over the way Britain had amalgamated disparate tribes into one artificial nation.

The Biafran war explained

Mam describes an idyllic childhood, in which war couldn't have been further from their minds.

"One of my earliest memories is catching an aeroplane from Heathrow to Lagos, then a smaller plane to Port Harcourt," she recalls.

"I remember the blistering heat as they opened the plane doors. I thought I'd never be able to survive it, but within weeks I'd got used to it."

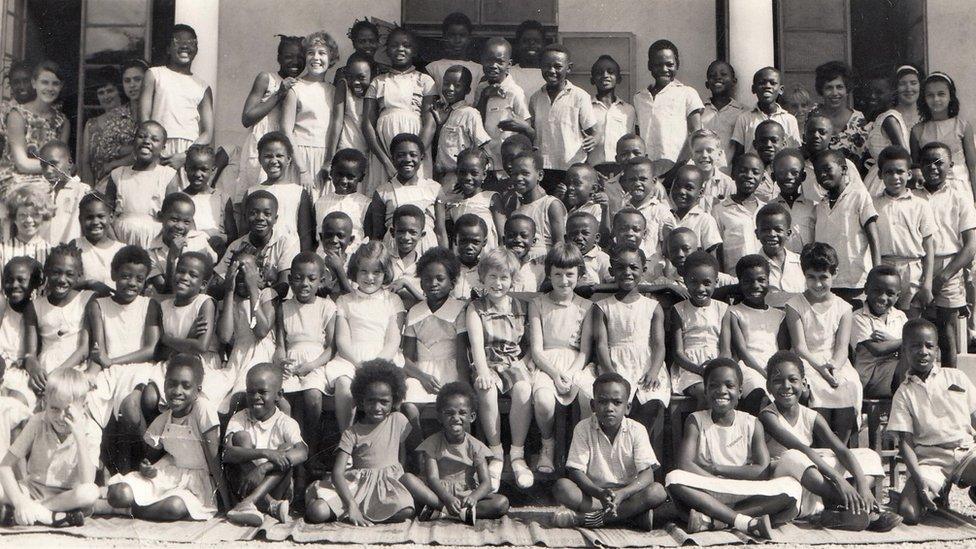

She was enrolled at Santa Maria school, and soon became a fixture at the Humkorshe swimming club.

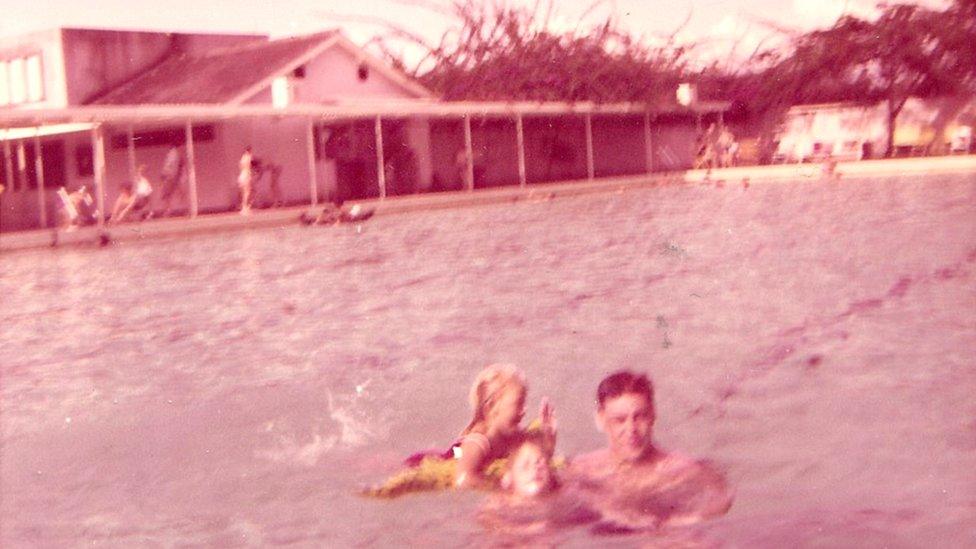

Swimming at the Humkorshe Club is one of Gaynor's fondest memories

"Getting up at about 05:00 to catch the minibus twenty miles to school was the worst part, and the nuns who ran the school were very, very strict. But on the up-side, we'd be finished by 12:30 and could spend the best part of the day doing as we pleased.

"For me that was swimming at Humkorshe, doing length after length and diving in the wonderful sunshine."

Mam soon made friends, and acquired an extended Nigerian family.

"We had a gang of five: Two girls, Ezikama and Stella who were my Nigerian friends, then there was Angelo, an Italian lad, and Michael from the north of England, both of those were the sons of oil workers.

"We'd cycle for miles and miles. Once we discovered an abandoned steam engine and made a den there.

"That turned out not to be such a good idea, as I got a poisonous spider in my hair, and had to cycle as fast as I could back to Michael's house, where his servant probably saved my life."

She speaks with fondness about the people who worked for them, but looking back she reflects on the inequity of the situation.

"It probably sounds wrong nowadays to say that we had servants, but Simon and Sunday weren't just servants, they were part of our family. They were my friends, confidants and fellow mischief-makers. I'd hate for anyone to think we were exploiting them, but in today's terms I suppose we were," Mam reflected.

"I still have a photograph of Simon which I sent back to my sister Susan, but so many of them, including all the ones of Sunday, I had to leave behind when we left."

Gaynor was a pupil at Santa Maria School in Port Harcourt

Then came the day in 1966 when Alan returned from work with troubling news.

Mam says: "Dad was very quiet. After a while he explained that the Igbo tribe had risen up in an attempt to establish an independent Biafran state.

"I said, 'but that won't affect us though right? Simon and Sunday are Igbo, there's no way they'd hurt us…?'"

What Mam hadn't considered was that Britain had backed the northern-dominated Nigerian army against the Biafran separatists.

Meanwhile, France was supporting the Igbo, setting up a proxy war between the two so-called allies for influence over West Africa and its oil reserves.

Biafran conflict: A grandmother's perspective on the war

Days later my grandmother, Doreen, received a call from Alan at work. They were given hours to flee the country.

"I don't know how close the fighting was to us, but the one thing which sticks with me is the sense of urgency. We had to get out that minute," Mam explains.

"I do remember we flew out on a Dakota [military transport aircraft], we had to get in from a ramp underneath."

Only women and children could leave Port Harcourt on the emergency flights. Alan had to travel overland to Malawi, and catch a flight home from there, which took several weeks.

Mam adds: "In the immediate weeks afterwards, I was of course terrified for Dad. Every night I cried myself to sleep about what had happened to Nero, but what I recall more than anything is my sister Susan being so angry that I'd taken all her teddy bears out to Nigeria, and had had to leave them all behind."

It's 55 years since Gaynor Prior left Nigeria

In the months and years which followed, Mam became increasingly traumatised by the fate of the extended family she'd left behind.

The Igbo people who had assisted British oil workers were persecuted within Biafra for their perceived treachery.

The region as a whole was blockaded by the Nigerian army. An estimated one to two million people starved to death before a ceasefire was finally signed in 1970.

"There's barely a day goes by that I don't think about what happened to all of them.

"If there's one thing I can do with this story," Mam says, "if a refugee, say from Afghanistan, ends up in the house next door to you, please please be kind to them. You have no idea what they've been through or who they've had to leave behind."

THE LONG WALK HOME: 20,000 miles, 4 years, 1 man

MOTHERS, MISSILES AND THE AMERICAN PRESIDENT: The story of Greenham told like never before

- Published16 September 2021

- Published10 September 2021

- Published9 September 2021

- Published6 September 2021