Oscar hopes for femicide documentary Dying to Divorce

- Published

Arzu Boztas lost both her legs and the use of her arms after being shot by her husband

"Don't shoot my arms, I won't be able to take care of my children."

These were Arzu Boztas's last words before her husband shot her multiple times, maiming her so badly she needed both her legs amputated and lost the use of her arms.

Hers is one of the stories told in Dying to Divorce, a low-budget documentary that is the UK's official Oscars entry for best international feature film and best documentary.

Its director, Chloe Fairweather from Abermule, Powys, spent five years making the film about the rise of femicide, external in Turkey.

More than one in three Turkish women have experienced domestic violence, the highest proportion among economically developed countries.

According to rights groups in Turkey, at least 345 women have been killed so far this year.

'Ruined my life'

The day Arzu suffered her life-changing injuries, she and her husband - the father of her six children - were due to go to the courthouse to get a divorce.

She said he had begged her not to divorce him after he took a mistress but had then agreed to divorce by mutual consent.

But he arrived that day with a shotgun.

She recalled the day's events while convalescing at her sister's home: "He said: 'Lie on the floor and stretch out your legs. I'm not going to shoot to kill you, I'm just going to make you crawl.' "

When she refused he shot both her legs.

"I didn't beg him not to shoot me, I begged for my arms," she said.

"I said: 'Don't shoot my arms, I won't be able to take care of my children'.

"I said: 'Even if I'm in a wheelchair I can go around after my children but what will I do if I don't have any arms?' "

Arzu has been learning to walk again using her prosthetic legs

She said he then pulled her arms from under her and shot each of them.

Arzu has since had both her legs amputated and lost the use of her arms.

"He's ruined my life," she said.

Arzu's father Ekrem Cansever regrets forcing his daughter to get married at 14

Her father Ekrem Cansever said he was "full of grief" after making her get married at 14.

"I feel guilty for marrying her off at a young age," he said. "I ruined the lives of my children. Why did I do it? So what if it's tradition?"

Speaking from Yozgat prison, her husband Ahmet Boztas said: "I wouldn't have gone so far but she insulted my pride and honour."

He blamed the government: "It's actually the laws in Turkey that have put us in that position, women have been encouraged to do wrong in the name of their rights...

"In the end it's the men that suffer."

He has since been sentenced to 20 years.

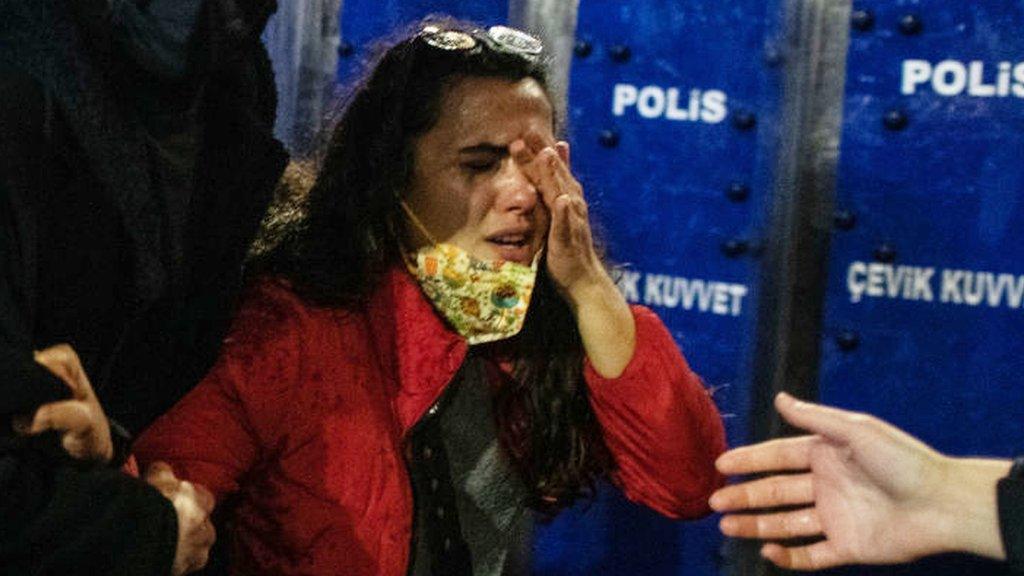

Kubra Eken was paralysed following an attack by her husband

Another women whose life has changed beyond recognition after being attacked by the man she once loved is Kubra Eken.

Kubra was a successful Bloomberg news presenter in London before she met her husband and moved back to Turkey to get married.

She suffered a brain haemorrhage and was left paralysed two days after giving birth to their daughter.

She said her husband Neptun hit her on the head four times following an argument. He said it was brought on by her C-section.

The film catches up with her two and a half years after her haemorrhage. She is living with her parents, uses a wheelchair and is slowly learning to talk again.

She has not seen her daughter since her injury. Her parents say she has been awarded access rights for three days a week but Neptun's family have not allowed any meetings to take place.

Kubra suffered a brain haemorrhage and was left paralysed two days after giving birth to their daughter

"When Kubra sees a mother and child on TV she is inconsolable," her mother says. "They always say they'll bring her and then they don't and Kubra is heartbroken".

The film follows her custody battle and Kubra learning to speak again in order to give her testimony in court.

Her husband was eventually sentenced to 15 months for assault.

'Unjust system'

Kubra's lawyer Ipek Bozkurt, a domestic violence activist, supporting many women who have similar stories to tell, carries out her work fearing her own arrest for speaking out against the Turkish justice system.

"This country protects murderers who would like to punish their wives, their daughters or their girlfriends who want to have different things in life than they did before," she says.

"You see how unjust this system is and have to fight against it."

Lawyer and activist Ipek Bozkurt champions the cases of women who have suffered gender-based violence

Amnesty International says the country's judiciary has disregard for fair trials and applies broadly defined anti-terrorism laws to punish acts protected under international human rights law.

Journalists, politicians, activists, social media users and human rights defenders suffer judicial harassment for their real or perceived dissent, it says.

In March the country abandoned an international accord that seeks to prevent, prosecute and eliminate domestic violence.

Turkish conservatives had argued its principles of gender equality and non-discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation undermine family values and promote homosexuality

Chloe and producer Sinead Kirwan spent five years going back and fore to Turkey to follow the women's fight for justice during a turbulent time for the country.

A failed coup in July 2016 was followed by a referendum in 2017 which gave sweeping powers to the country's powerful but divisive President Erdogan.

'Total underdog'

Chloe said funding issues and the lengthy judicial process the women in the documentary went through meant the project was a "difficult road" and she sometimes feared it would never be completed.

"There was so much momentum to make the film because it just felt so urgent that this story should be out there," she said.

"The women were just so inspiring and they were changing their lives and moving forward and overcoming unbelievable challenges and just getting stronger and stronger in the face of those challenges."

Chloe Fairweather is glad the film's acclaim means the "really important issue" of femicide is getting attention

Hearing the film had been selected to represent the UK in two categories at the 94th Academy Awards was a shock.

"We were definitely surprised. I was like: 'What? What? Serious?' " said Chloe.

"You feel like you're a bit of an outlier when you make a film in this way, like a total, total underdog so we were really surprised but also really delighted that the film would get recognition in this way and definitely that the issue would get recognised as being a really important issue."

THE MUSICAL LIFE OF: Stories of the greatest ever Welsh people through song

THE ASIAN WELSH: How immigration from the Indian subcontinent transformed Welsh health, culture and the economy

- Published26 November 2021

- Published25 November 2021

- Published22 November 2021