How Falklands War and rugby led to 40-year friendship

- Published

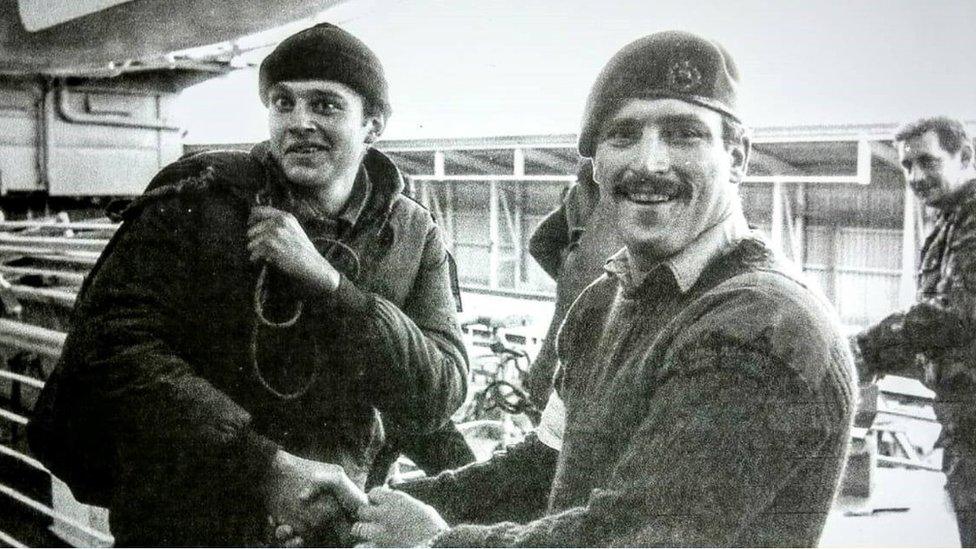

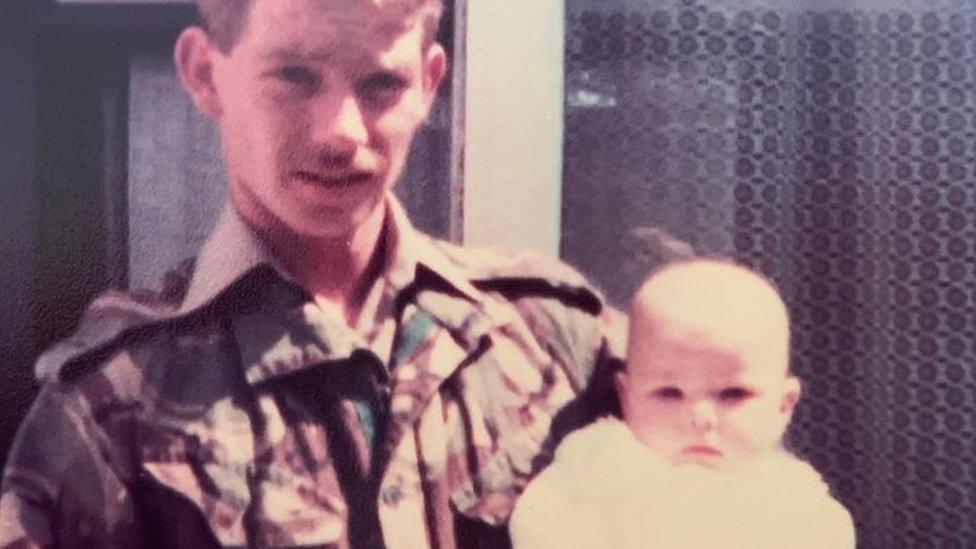

Giorgio and Irfon struck up an unlikely friendship as prisoner of war and guard

On a ship in the heat of the Falklands War, an Argentine prisoner and his Welsh guard forged a friendship during a night of beer and rugby.

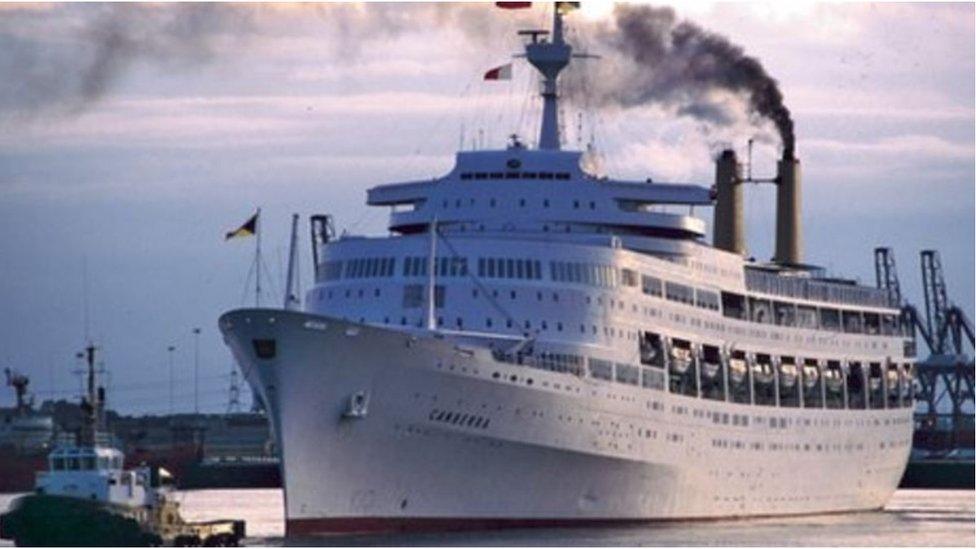

Irfon Higgins was a soldier on the SS Canberra, tasked with guarding 4,500 prisoners of war, or PoWs.

When Irfon asked who spoke English, PoW Giorgio Podesta answered "I do".

Nearly 40 years after Giorgio helped him stop a mutiny, Irfon says: "I can't imagine my life now without him in it".

Their story has been recounted in a book on the 1982 conflict by Brian Short - The Band That Went to War.

Recalling the day he met Giorgio, Irfon said: "I was guarding 4,500 PoWs on the Canberra, and trying to escort them in groups of 10 to the shower.

"It was like herding cats, so I shouted 'Do any of you speak English?'

"Giorgio said 'I do', and from then on he became my go-to man and interpreter."

Irfon says those aboard the Canberra were not expected to survive the war

Giorgio admitted he had been reluctant to learn English as a child, but it had ended up helping him through the war.

"My mother sent me to take English classes, against my will, with the excuse that 'at some point you will need it'," he said. "I was happy because I was talking in English with Irfon. After all the hardships of war, now I felt safe, fed, warm and with a friend."

At Easter 1982 Royal Marines Commando Band saxophonist Irfon was playing rugby for his regiment in Plymouth when he was called off the pitch with a vital message.

They'd been mobilised to travel to the Falklands as part of the British task force. Argentine forces had landed on the Falklands to stake a territorial claim to the islands, which it calls the Malvinas.

Chandeliers and shoulder-launched rockets

"When you tell people you were in the Royal Marines they instantly think you were some kind of hard nut. But I was just a musician, not a proper soldier, so I was amazed that we'd been called up at all," said Irfon, from Ammanford, Carmarthenshire.

"I was excited as much as anything, and for the first few weeks until we reached Ascension Island it all seemed like a dream."

But Irfon had one important matter to settle before going to war.

"My wife Jan and I had been due to get married that summer, and I didn't want to go away without tying the knot," he said. "So we got an emergency licence, and were married in May, just before I left - none of the boys could come as we were confined to barracks before sailing, but we had a do in the mess afterwards."

They spent the first few weeks of the voyage sunning themselves on the deck.

As the weather changed from northern hemisphere summer to southern hemisphere winter, Irfon said the mood aboard the Canberra also altered.

"Initially we couldn't believe how lucky we were going to war on a P&O cruise ship, the luxury was like nothing any of us had ever experienced before," he said. "It had just come off a Mediterranean cruise, so the ballrooms, chandeliers, food and drink were out of this world.

"But as we entered San Carlos Sound we realised how vulnerable we were."

'Sitting ducks'

As a requisitioned cruise ship, the Canberra had no defences other than a few machine guns mounted on the rails and the shoulder-launched rockets carried by the Parachute Regiment.

They soon came under attack from the Argentine air force.

"We were designated as a hospital ship, but as we'd also transported troops we weren't able to claim the protection afforded under the Geneva Convention," said Irfon. "Really we were sitting ducks, and after the war we discovered that the British government had already factored in losing the Canberra early on; they expected us to die."

After offloading the Parachute Regiment to landing craft, the Canberra travelled to South Georgia to convey Welsh Guards and Gurkhas to the Falklands.

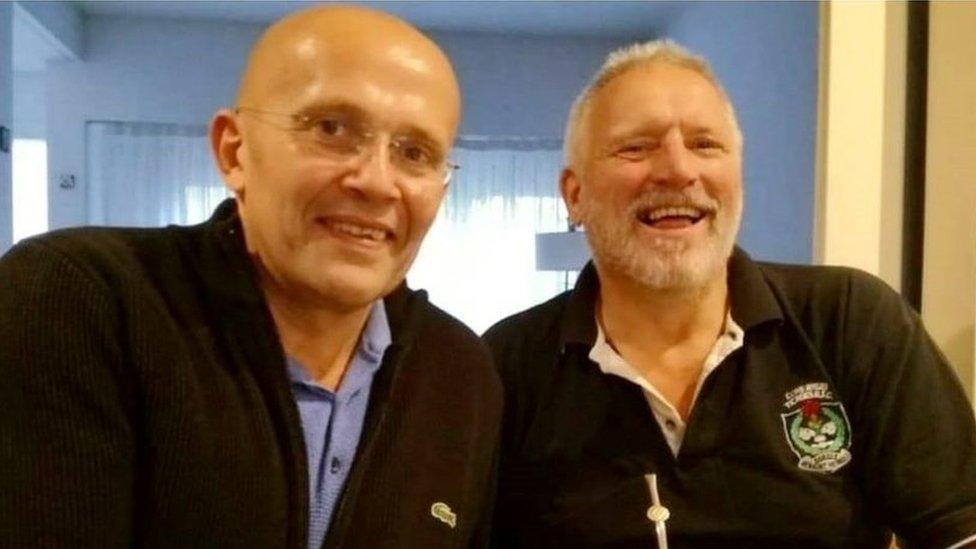

The friends still meet up, 40 years on, to chat about rugby over a beer

As the fighting ensued, the ship soon started to receive helicopter loads of both injured British and captured Argentinians.

"As we saw the hideous injuries our boys were taking, it was hard not to take it out on the PoWs," said Irfon.

'JPR and JJ'

But as hostility grew between the enemies, a friendship was also blossoming.

"Once I started talking to Giorgio about Welsh rugby - JPR and JJ - I soon realised we had far more in common than I did with many of the British troops," said Irfon.

"There were some who were hardened special forces dedicated to the military junta, though most - like Giorgio - were conscripted soldiers who didn't want to be there any more than we did. One night I smuggled him out of the ballroom where the PoWs were being held, and took him up to my cabin for a night on the beer and a proper chat about rugby," said Irfon.

Giorgio said the talk centred around the match "between Los Pumas and Wales in 1976, in which Wales beat us at the last minute with a penalty kick by Phil Bennett, and the legendary Gareth Edwards, and fullback John Peter Rhys Williams.

"We talked about our homes, our families and our friends. Wishing to return to our homes soon. He took the opportunity to introduce me to his friends and cabin mates. The smile returned to my face."

Ever since that night, Irfon and Giorgio have been firm friends. But it was not just beer and sport that cemented their relationship.

Author Brian Short, who was aboard the Canberra at the time, said: "What both he and Giorgio are too modest to say is that between them they prevented a mutiny on the ship.

"On the way to Puerto Madryn, Giorgio tipped off Irfon that some of the diehard Argentinians were planning to seize the ship by force. Irfon and I held both ends of the corridor with a machine gun each, and in the end there was no trouble at all."

Goodbye on the gangplank

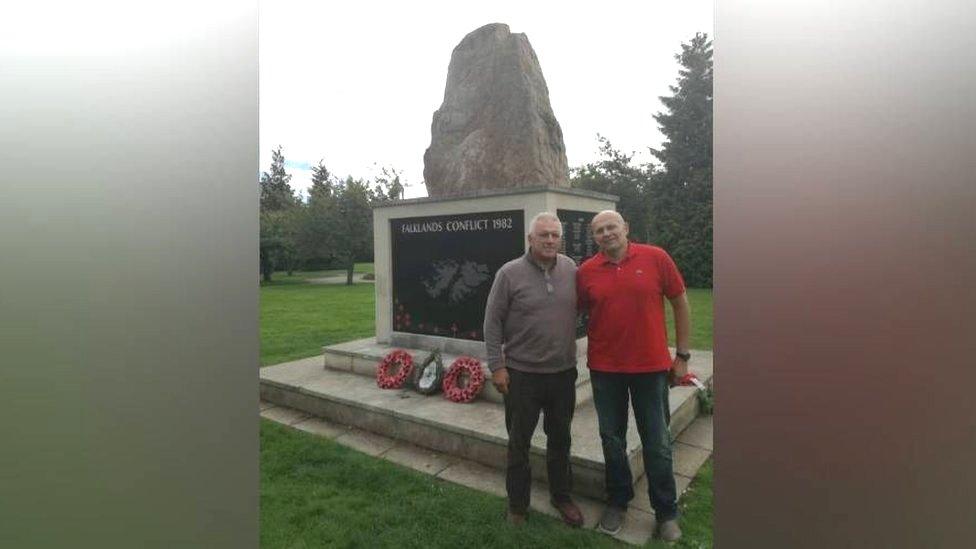

Irfon and Giorgio have visited the Cardiff Falklands Memorial, pictured, as well as its Buenos Aires equivalent

After a brief but bitter 72-day conflict, British forces regained the Falklands and ejected the Argentines. As the Canberra repatriated the PoWs to Puerto Madryn - the Welsh-speaking enclave of Argentina - in July 1982, a Navy photographer captured Irfon and Giorgio sharing a heartfelt goodbye handshake on the gangplank.

The pair lost touch for a few years, with difficulties getting letters between Wales and Argentina. But soon enough, Irfon's wife Jan found Giorgio.

"We've been out to visit him, and he's been over to Wales - I can't imagine my life now without him in it," said Irfon.

The story of their friendship is just one of dozens of similar ones in Brian Short's book.

Although the war caused so much suffering and death, he said he wrote it to seek out the good which came from the chaos.

SLAMMED: The story of Wales’ transformation from rugby rejects to rugby royalty

STORIES FROM WALES : Documentaries for curious minds

Related topics

- Published8 November 2021

- Published2 September 2014

- Published2 August 2016

- Published26 April 2018

- Published11 August 2015